Highett Gasland

Aerial view of Gasworks Site, c1970. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

With the discovery of natural gas in Bass Strait in 1965 and the gradual conversion of gas appliances to use this resource the future viability of the Highett gasworks as a production unit was being explored. At Highett the gas produced came from coal so the large plant was no longer needed. A spokesman for the Gas and Fuel Corporation, the owner of the property, agreed in 1969 that some of the land at Highett would be superfluous to their needs and could be sold. While at this stage sale of the land had not been discussed he acknowledged that the Moorabbin Council had expressed interest in purchasing some of the land adjoining the recreational land it owned in Graham Road. However, he warned that there was unlikely to be any action on the matter before the end of the following year. [1]

It was not until 1974 that the Gas and Fuel Corporation announced its offer to either the Moorabbin Council or the State Government of eight acres of land on Graham Road for $350,000. This offer was seen to be unsatisfactory to a recently established committee called “Gasworks Land for the People.” They wanted twenty acres. The committee consisting of members drawn from the Southmoor Cricket Club, Cheltenham Baseball Club, Port Phillip Environment Centre, Cheltenham East Progress Association, Southern Fly Fishers Club, Moorabbin Chamber of Commerce, Moorabbin Branch of the Amalgamated Metal Workers Union, Hotham Australian Labor Party, Southern Young Labor Association, Zero Population Growth and individual citizens. Peter Spyker as acting secretary of the committee called upon the Moorabbin Council to rezone the land as community parkland and added the threat that if this were not done the committee would approach the Trades Hall Council to place a ‘green ban’ on the site. [2]

Moorabbin Council was dismayed about the Gas and Fuel offer which they first learned about through a newspaper report. The mayor, Cr Stevens, said the announcement came as a surprise considering the fact that the Council had been negotiating with the Gas and Fuel Corporation for six months in an effort to get the land. Cr Don Bricker complained that the Corporation was asking top price for the offered eight acres at $45,000 and acre. Cr Ken Reed thought it was unjust to expect Moorabbin to pay the current market price, as since the early thirties Moorabbin people had to suffer the smells and unsightly appearance of this public utility which served areas outside the municipality. He thought the council was entitled to more than eight acres and he expected the government to provide assistance with the purchase. Later, Cr Stevens said the land was being offered at a ridiculous and outrageous price. Cr Don Bricker described it as a useless piece of land on which any good cricketer would slam hits into passing trains. If an oval were graded there it would only be suitable for juniors, he claimed. [3]

Local members of parliament, being part of the government, were more cautious in their responses when asked their opinions on the proposed deal. Llew Reese, the Member for Moorabbin, thought it would be a tragedy if an adequate area of land was not set-aside for the people. When he was quizzed further as to the meaning of “an adequate area” he responded “room for an oval or similar open space on the highway side.” Bill Fry, a member of the Legislative Council, also agreed that a reasonable amount should be turned into a park but believed it was up to the Moorabbin Council to make the decision on what was needed. Whatever was decided he said he was prepared to take it to the Premier and seek financial assistance. [4]

N A Smith, the chairman of the Gas and Fuel Corporation, in a letter to the Standard News explained the position of the semi government utility which had approximately $16 million of its capital subscribed by government and $6 million subscribed by private shareholders. As the sole supplier of reticulated gas in Victoria it had a responsibility to provide gas supply to all parts of the State wherever it was financially viable. With the introduction of natural gas the production plant at Highett became redundant so the Corporation began exploring future possible uses of the site. It was found that while a portion of the site was required to maintain customer services a considerable area was no longer needed and could be made available for sale for public or private purposes. As a result the Corporation offered the Moorabbin Council approximately eight acres for $350,000. This same piece of land, Mr Smith said had a buyer prepared to pay $500,000. The remaining land of the twenty acres was to be sold with the proceeds being used to build a pipeline to supply natural gas to Seymour, Shepparton, Benalla, Wangaratta and Wodonga. Obviously, he said, consumers in other parts of Melbourne cannot be expected to subsidise a development for the sole benefit of the ratepayers of Moorabbin but if Moorabbin Council wished to buy the remaining land at a realistic market price the Corporation would be happy to negotiate directly with the Council rather than offering the land for sale at auction or public tender. [5]

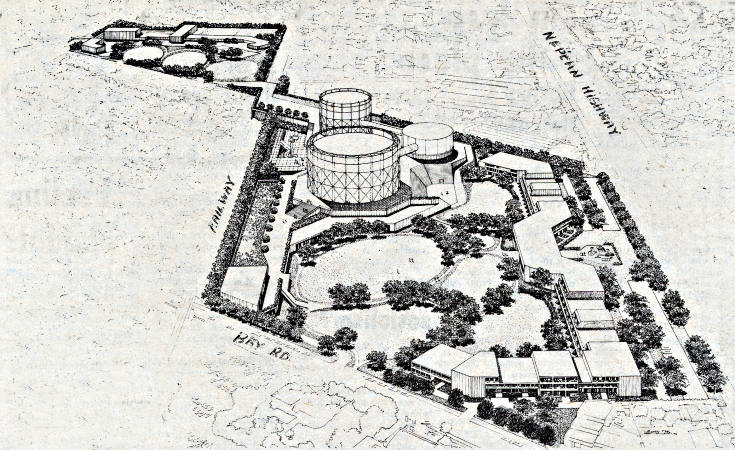

The Council went ahead and engaged the firm of Yunchen Freeman Architects to prepare a plan to show how the site could be utilized for public use, for recreation and for open space to serve the needs of the whole municipality. While the plan was not intended to be definitive it was expected to show the development potential of the site. The aim of the architects was to include the three gasometers in their design by removing the tanks to reveal the light and delicate tracery that could support a lightweight or glazed structure. They then could be fitted out to provide a major theatre complex, galleries, restaurants, a conference and convention centre as well as a community centre. There was even suggestions of a science centre, a space museum and planetarium. The whole structure they saw as a buffer against the noise and ugliness of the railway to the eastern section of the site. In the southern portion of this eastern section it was suggested town houses could be built for under- privileged people, either for sale, lease or rental. This area would be screened from Nepean Highway by dense landscaping and it was within this area it was thought a crèche or kindergarten could be located.

Architects’ drawing of possible use of gasworks land, 1974. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

On the western side of the property, close to both the Highett Primary School and the Highett Bowling Club, provision was made for a sports or community centre that offered a wide range of facilities for use by residents. Consideration was given to gymnasia, tennis club and squash courts, meeting rooms and space for administration staff. Overall it was envisaged that the property would provide for a wide variety of outdoor activities, both organised and spontaneous active recreation, including bicycling, barbeque areas and playgrounds.

The members of the Gasworks Land for the People group while recognising the tentative nature of the plans were unhappy with the suggestion of a row of town houses along Nepean Highway, and a restaurant. Their spokesman wondered why it was necessary to employ architects to plan a park. After all, he said, it is a natural park that is wanted. [6] Tony Ross, the Australian Labor Party candidate for the electorate of Hotham in the foreshadowed election, stressed the importance of the gasworks committee being represented on the council delegation to State premier, Rupert Hamer. He didn’t want the premier to get the idea that Moorabbin people supported the lavish proposal put forward by the Council’s architects a short time previously. If they were not included they would seek their own deputation and would make a direct approach to the Federal Labor government for assistance. [7]

Mr Hamer told the deputation consisting of the mayor, Cr Stevens, Cr G Bricker, the town clerk, J Waters, and city engineer, W Dennis, that the State Government, in conjunction with the Council, would take steps to secure the land for the people of Moorabbin for recreational and public purposes. The premier also agreed that when the agreement was finalised the council would take control of the development and use of the land. However, how the land was to be paid for was still unclear. Nevertheless, the Moorabbin councillors and Peter Spyker, secretary of the Gaslands for the People Committee, welcomed this news. [8]

After the excitement of the announcement had subsided some cautionary voices were heard. The mayor confirmed that Mr Hamer had given a commitment to assist council in the purchase of the land but warned there is every possibility that negotiations could fall through. “The Gas and Fuel Corporation is an autonomous authority and they want the highest price possible for their land,” the mayor stated. The Council was not going to get the land for free. Development costs were estimated between $100,000 and $300,000 and this money was on top of its share of the purchase price estimated to be $1 million. [9] One estimate of value was nearly $4 million for the 11.68 hectares of land.

In June 1975 the Gas and Fuel Corporation withdrew its offer of eight acres of land on the west of the railway line to the Moorabbin Council in order to begin negotiations with the Housing Commission of Victoria. [10] It was not until the next year in March that an agreement between the premier, Rupert Hamer, and councillors Bricker and Stevens from Moorabbin, was reached about the future of the twenty acres on Nepean Highway. Officers of the Council together with local parliamentarians, Llew Reese, Max Crellin and Bill Fry, were also in attendance at the meeting. The effect of the agreement was that the State Government decided to purchase the land from the Gas and Fuel Corporation and make it available to Moorabbin Council as a committee of management. Llew Reese welcomed the outcome of the meeting pointing out the Council was now free to plan and develop it as it determined provided the basic concept of open space available for all citizens and with emphasis on beautification and a parkland setting was maintained. [11] The comment of Peter Spyker was that careful watch would have to be taken that the Council didn’t waste the valuable land with the grandiose scheme of town houses and theatres in the gasometers like the plan it prepared two years earlier.

By October 1983 people were still arguing about the use to which the gaslands should be put. After an election the State Government had changed with the Labor Party taking charge. The Council informed the new government that if the large tract of land in Nepean Highway could not be planned and developed as they saw fit then the government could have it back. Cr David Story, a solicitor by profession, informed his colleagues that it would be foolish for the Council to spend vast sums of ratepayers’ money only to lose management control, a situation that could occur as the Minister had the power to revoke the council’s trusteeship at any time. He believed the councillors who had negotiated the deal with the government in the 60s didn’t do their homework, as any buildings and facilities they placed on the site would be lost if government revoked their trusteeship. Cr Keith Duckmanton, the chairman of the Council’s gaslands committee, reiterated the Council’s intention to use the existing concrete base to build an indoor sports complex and proposed they should seek the approval of the state government to develop it this way. Should they refuse to grant approval then council should relinquish rights of management. The Council strongly rejected the government’s view that the park should be developed for passive recreation and open space. [12]

The concrete base of a Highett gasometer, 1987. Courtesy Peter Dack.

Local members of parliament, Graham Ihlein and Peter Spyker, were adamant that the government view was the correct one. Mr Ihlein said the land was given to Moorabbin for passive recreation and that meant mainly grass and trees. The Council, he believed, wanted to do the opposite, to build indoor sporting complexes, cultural centres with parking areas and this was not in the spirit of the original agreement. Mr Ihein said further delays should not be tolerated. [13]

The Moorabbin City Council through the town clerk, G W Jacobs, placed an advertisement in the local newspaper detailing salient points about the history of the gaslands saga and what the council was proposing. The advertisement drew attention to the fact that the Department of Youth Sport and Recreation in 1982 made a grant of $250,000 over a period of ten years towards the development of an indoor sporting facility and that extensive improvements had been made to what was formerly a barren site. These improvements included water reticulation to facilitate the growth of trees to create an attractive parkland setting, a landscaped hill and strategic tree planting. The utilization of the base structures of the gasometers minimized the cost of constructing stand-alone facilities at another site and their use provided a historical and recognisable landmark to their former use.

The developmental plan adopted by Council included a fun and fitness track, tennis rebound wall, geographical education park, children’s playground, roller skating arena, skateboard arena, landscaping, barbecues, public toilets, access road and car parks, public lighting, and drainage. In addition, a quiet bushland area was planned for the western side of the railway line at the Highett Grove Reserve. This development included an extensive tree-planting program undertaken in accordance with Council’s advanced tree propagation program.

A Council deputation met with R A Mackenzie, the Minister for Conservation, Forests and Lands, on October 4, 1983 in response to his correspondence in which he expressed his concern that the Council had departed from the spirit of the 1976 agreement about the use of the land. At that meeting the Council told the minister that several major reserves had been created since 1969 in close proximity to the gaslands which were catering for passive recreation. These reserves were Basterfield Park, and Kingston Heath Reserve in Centre Dandenong Road. In addition, improvements had been made to the Crown Land Reserve known as Cheltenham Park. The neighbouring council, Sandringham, had developed the Heathland Sanctuary in Bay Road as a natural reserve, only a short distance away from the gaslands site. [14]

Ministers Peter Spyker, Evan Walker and Rod McKenzie inspecting the base of the gasometer at Highett from a cherry picker, 1984. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Following the deputation with the minister a council meeting decided to seek his approval for the Gaslands development which included an indoor multi-purpose sports centre using the existing concrete gasometer base. Should the approval not be given the Council resolved at that time to surrender their rights of management over the reserve believing the reserve was not going to be developed in the best interests of the residents of the municipality. [15]

Twelve months later the Council announced that the plans for an indoor sports centre had been shelved. Much of the blame for this was directed at local parliamentary member, Graham Ihlein, who, according to Cr Ron Brownlees, had ‘impertinently interfered” in the whole proposal. The Minister for Youth Sport and Recreation had earlier advised Council that the State Government grant of $250,000 to go towards the cost of the sports centre was withdrawn. The Moorabbin town clerk, Bill Jacobs, said that Council’s prime attention was now directed towards the planning of a new administration centre and possibly an arts and cultural complex expected to cost about $5 million. However, a working party would continue with the development of the site as an area for passive recreation. [16]

On March 6, 1985 it was announced that the new park, previously referred to as the Gaslands Reserve, was to be named the Sir William Fry Reserve in recognition of his outstanding contribution as a councillor and member of the Legislative Council. Bill, as he was known to friends and acquaintances, had been a principal of a local primary school, and a councillor for twelve years, including a period as mayor in 1969-70. Later in his career he was elected President of the Legislative Council and was made a knight bachelor by the Queen on July 23, 1980 because of his community work.

Cr W G Fry, Mayor of Moorabbin 1968-69. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

It was not until February 1987 that the warring factions in Council and State politics reached agreement about the development of the reserve, thus allowing it to proceed. Mrs Joan Kirner, Minister of Conservation, Forests and Lands, approved the Council’s preferred option which included an indoor sports complex using the remaining gasometer, a sound shell, ornamental lake, children’s playground and open space. Provision was being made for basketball, badminton and gymnastics in the indoor facility. The notion that the concrete base of the gasometer should be removed at a cost of $100,000 seemed to have evaporated. However, the first stage of the development was expected to cost $186,891 and approval had been given for the construction of a children’s playground for which $47,000 had been contributed by the Ministry of Sport and Recreation on the basis that the council would contribute dollar for dollar.

Demolition of Gasometer at Highett, 1988. Courtesy Peter Dack.

By October 9, 1987 the superstructure of the gasometers had gone and a little over twelve months later work was proceeding on the demolition of the remaining gasometer wall. The building of the children’s playground was complete by December 10, 1988 together with the planting of trees and shrubs, and the provision of parking for cars, all allowing for the official opening of the park by the mayor of Moorabbin, Cr Ronald Brownlees, of what had become a joint Council and Australian Bicentennial Project. Three years later, after the excavation of the lake had been completed, it too was officially declared open by the mayor of that time, Cr Neil Bennett. By then a major redevelopment of what was formerly known as the gaslands reserve was well on the way to completion after a torturous path of argument and indecision. However, the indoor sports complex, a feature over which many men had fought a bitter campaign, was still to be built.

Official opening of lake at Sir William Fry Reserve, Highett by Mayor of Moorabbin, Cr N P Bennett, July 7, 1991. Courtesy Peter Dack.

Footnotes

- Moorabbin Standard News, July 23, 1969.

- Moorabbin Standard News, March 20, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, March 13, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, May 8, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, May 8, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, May 15, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, June 5, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, June 12, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, June 19, 1974.

- Moorabbin Standard News, July 2, 1975.

- Moorabbin Standard News, March 17, 1976.

- Moorabbin Standard News, October 26, 1983.

- Moorabbin Standard News, October 26, 1983.

- Moorabbin Standard News, November 9, 1983.

- Moorabbin Standard News, November 9, 1983.

- Moorabbin Standard News, October 17, 1984.