The Cheltenham World War One Memorials

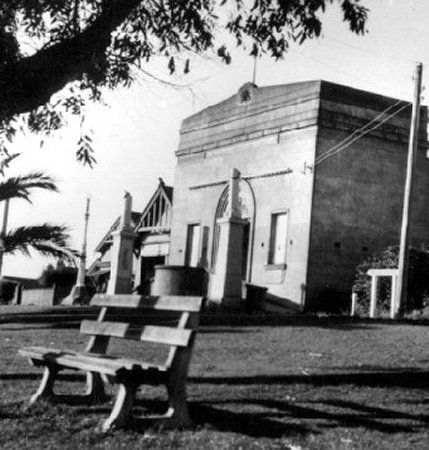

World One Memorials outside the Soldiers’ Hall Cheltenham, c1945. Courtesy Leader Collection.

World War One was over and by the 1920s the Australian troops who had fought in Europe and other overseas locations had returned home. Many individuals, however, did not return being buried in places close to where they died in battle. It was the sacrifice of these men that communities throughout Australia wished to acknowledge through the construction of memorials. This community feeling existed in the Shire of Moorabbin.

In September 1923 a meeting at Cheltenham was called by the president of the Shire, Cr Clements, to consider what steps should be taken to provide a suitable memorial to their war dead. The meeting, held in the Soldiers’ Hall in Cheltenham, was not well attended but those who were there were enthusiastic about a proposal that £1000 should be raised to erected a suitable memorial. The task of raising this amount of money in a wealthy district like Cheltenham where people were generous was not seen to be an unrealistic goal according to Cr Clements. However, he was aware that the ‘glamour’ of war was dissipating and there was some confusion in the minds of the residents with previous appeals to raise money to provide a soldiers’ hall and funds to support stressed former soldiers. He emphasised that the hall was never intended to be a memorial to the fallen and pointed to the fact that both Mentone and McKinnon had raised fitting memorials to their dead. [1] It was time that Cheltenham did the same, he said.

Mr David, the general secretary of the State branch of the Returned Soldiers’ Association, suggested a monster public meeting where people would be gathered so their support for the project could be enlisted. This could be followed by a button day or a house-to-house canvass to be concluded with a spectacular display. He realised that some people wanted to forget about the war as they feared it might ‘touch their pockets’ but he believed people’s consciences had to be awakened. [2]

Raising the £1000 proved more difficult than the organising committee and other interested individuals anticipated. A second public meeting was only marginally more successful in attracting participants. This poor attendance was attributed to the confusion existing in the minds of the residents about the relationship between the proposed memorial and the soldiers’ hall which had been purchased with the financial assistance of local residents. Questions being asked included, “How was the money used that was raised on that occasion?” “Was it not for a ‘memorial’ hall?” and “Why the need for a further memorial?” Subsequently the Moorabbin branch of the RSA presented the exact financial position of the hall to make it clear that the movement for a memorial was independent and entirely distinct from the hall which had to finance itself. The statement showed that the hall had originally cost £1750 with £225 being spent on furniture, lights and fittings. In total, £2405 was spent leaving a debt of £400. There was a proposal to carry out some renovations costing £1150 which would be financed through a loan of £1000. £80 was in hand and the balance would be income derived from hiring the hall. [3]

The notion of holding a Queen Carnival to raise the money for the memorial was suggested together with the idea of imposing a special levy of 3d on all ratepayers. One individual believed the Council should be giving a lead on the matter as it was a civic issue but was informed that the Council was reluctant to do this unless the memorial was erected in Moorabbin. The returned soldiers themselves saw the memorial being erected in Cheltenham with a preference for marble columns on each end of the ramp leading to the entrance of the Soldiers’ Hall with an honour board in the porch and a cenotaph similar to that at Whitehall in England. [4]

World War One Memorials in Cheltenham Park, 1988. Courtesy Leader Collection.

The Shire Council took up the issue of the memorial at a meeting in November. On that occasion the councillors were informed of the recommendation of the earlier public meeting that a civic memorial should be erected as an adjunct to the Soldiers’ Hall at Cheltenham at an estimated cost of £600. It was pointed out that the memorial would include the names of the men who had enlisted from the Moorabbin and Cheltenham ridings, Beaumaris and portions of Mentone. To assist with the project the Council was asked to contribute £250 over five years. Cr Clements, the shire president, supported this request provided the Soldiers’ Hall became public property in period not exceeding ten years. Other councillors expressed support for this position but doubts were raised as to whether the trustees of the hall had the power to hand over the building. After further discussion at a subsequent meeting, the Council agreed to allocate £50 each year for five years from funds of the Cheltenham Riding towards the cost of erecting a memorial to the 108 dead soldiers who enlisted from the Shire. This was done on the understanding that the Soldiers’ Hall would be handed over to the council on a date to be arranged for a nominal sum and that such proceeds be used for the relief of distress amongst returned soldiers. The memorial was to be known as a shire memorial. [5]

One of the two World War One memorials now at the Cheltenham RSL Club, Centre Dandenong Road, Cheltenham.

Eight months later, in July 1924, the citizens’ committee returned to the Council asking that the promised contribution rather than being paid in instalments over a period of five years be paid immediately in a lump sum. [6] This need had arisen because the contributions from the public had been much less than anticipated and without the change in the delivery of the Council contribution the completion of the memorial would be delayed for some years. While the committee had sent out 1500 letters to ratepayers only about five percent responded, but with Council’s agreement to advance the grant of £250 the committee resolved to proceed with the project at a total cost of £520. Mr Butterworth prepared a design and various monumental masons were interviewed to obtain prices. As a result of this action J Robinson of Carlton was commissioned to construct and erect the memorial which took the form of two obelisks. The base of each was about 4 ft 6ins square topped by a square 6 ft 6 in high pillar weighing over three tons. On the pillars were inscribed the names of the fallen soldiers. Surmounting each pillar was a 6 ft broken column on which was attached a bronze wreath. Constructed in Harcourt granite the total height of each obelisk was nineteen feet.

Walter (Wally) Rose places a wreath on memorial, c1944. Courtesy Arthur Rose.

While there was a short delay in the construction and erection of the memorial due to the difficulties experienced in obtaining the unusually large pieces of granite, all was ready for the unveiling on Anzac Sunday, April 26, 1925. Before an audience, the largest seen in the district for some time, Brigadier General Drake-Brockman unveiled the memorial and spoke of the fine calibre of Australian men who fought during the Great War. They were men of whom the community could be proud, he said. While some writers claimed they were undisciplined he disagreed, pointing to the fact that there was no record of an AIF member being a traitor. Moreover, he suggested their bravery could not be disputed. He told of one instance near Bullecourt during an attack on the Hindenburg line where 870 men and 33 officers ‘went over the top’ but only 87 men and 3 officers returned. Mr Turnbull, President of the Returned Soldiers League of Victoria, thanked the organisers for his invitation and reminded all present that erecting memorials did not relieve anyone of their obligation towards the returned soldiers. [7]

To conclude the ceremony the Rev Fowler pronounced the Benediction, the Moorabbin and Mordialloc Bands under the leadership of Mr Brine played the “Dead March” and Bugler Whitford sounded the “Last Post”. A collection and contributions on the day raised £42-14-4 towards the existing debt of £60 making the memorial almost debt free.

Bugler W Fawcett playing the last post at an Anzac Service in the Cheltenham Park, 1963. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Footnotes

- See Whitehead, G., Soldiers’ Hall, [localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au], article 211.

- Moorabbin News, September 29, 1923.

- Moorabbin News, October 20, 1923.

- Moorabbin News, November 10, 1923.

- Moorabbin News, November 24, 1923.

- Shire of Moorabbin Minutes, July 21, 1924, page 1267.

- Moorabbin News, May 2, 1925.