The Beginning of the Cheltenham Golf Club

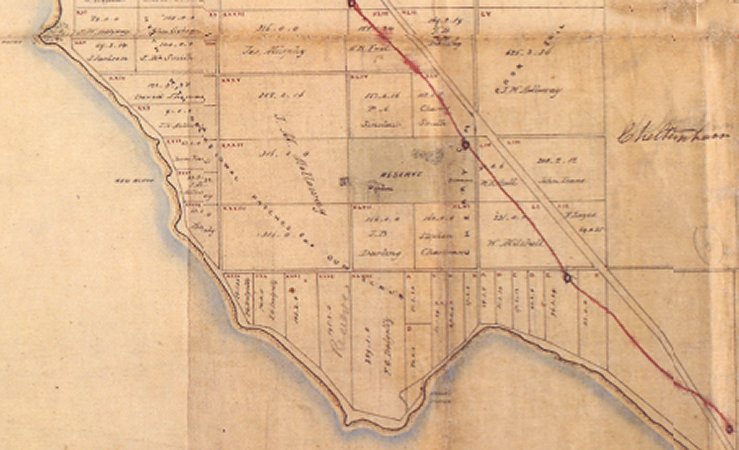

When the survey of the land surrounding the infant town of Melbourne was completed in the early 1850s and the land offered for sale by auction, many men took the opportunity to become landowners in the Port Phillip Bay District. Early maps give the names of these selectors. Maps of the Parish of Moorabbin include the surnames Charman, Darling, Holloway, Sinclair and Smith but also include a portion listed as Reserve. Bounded today by Reserve Road, Park Road, Weatherall Road and Charman Road this piece of land included two springs and a section of swamp. This land became known as the Cheltenham Park.

Portion of the Parish of Moorabbin showing the Cheltenham Reserve. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

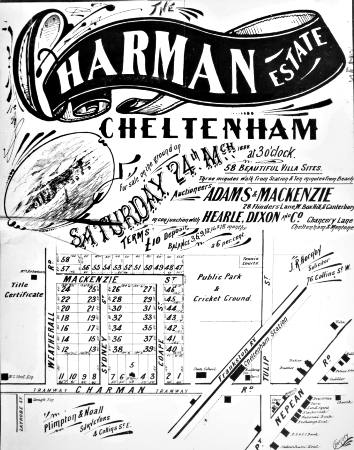

Since the survey and the nomination of a portion of the Parish of Moorabbin as a reserve, a significant part of it has been whittled away by grants, assignments and sales. In 1863 eight acres was set aside as the South Moorabbin and Mordialloc General Cemetery with the first burial occurring in March 1865. [1] The Presbyterian Church was granted one acre three rods twenty six perches in 1869 to be followed by a similar sized grant to the Wesleyan Church in 1870. Both grants faced Charman Road. In the same year land was provided for the building of Beaumaris School, later to be renamed Cheltenham State School No 84. It was two years later on July 26, 1872 that the Cheltenham Park was listed and described in the Government Gazette. Subsequent to this event several acres were sold to different purchasers. James Phelan purchased 136 acres 2 rods 17 perches, a significant portion of the total reserve in 1875. The following year saw J Rusk, Crawford, W Cook, and Fraser, individually making purchases. Some of this land was subdivided and sold in 1888 during a land boom at substantial profit. [2]

Land Sales Poster for the Charman Estate, 1888. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

From May 8, 1879 the responsibility of managing the Cheltenham Park passed to the Moorabbin Shire Council. [3] But this did not inhibit the assignment of land in the Cheltenham Park to a variety of users. Four months after taking charge of the park, the shire council set apart six acres as a cricket ground for the Rising Star Cricket Club. [4] Later a further one acre was set apart for a lawn tennis club but a request for use of the park by the Rifle Club was denied owing to the possible danger to life from its activities [5] With the construction of the Melbourne to Mordialloc railway line in 1881 further park land was reassigned as also happened when the Cheltenham Recreation Reserve was established in 1894 and the Cheltenham Bowling Club in 1907.[6]

The Victoria Golf Club took up residence in Cheltenham in 1927 on part of the 140 acres of freehold land that was originally granted to James Phelan in 1875. The club purchased 128 acres of the land in 1922 which by that time was held under ten separate titles. The largest holding of 108 acres was in the names of W F Vale and P A Jackson. The total cost of the land was £24,319. [7] A vermin proof fence was erected around the estate and Cypresses Lambertinia planted just inside the fence. In addition a planting program of gums, acacias and other trees was implemented. Shortly after their arrival in Cheltenham the club applied to the council for permission to park cars on a section of the Cheltenham Park “if it was found necessary.” This caused some animated debate in the local community. [8]

Victoria Golf Club, Cheltenham. Courtesy Eric Longmuir.

The shire council received a letter from the Lands Department informing it that no steps should taken in granting use of land in the Cheltenham Park until the Minister of Lands considered the matter. [9] The following week the local newspaper reported the news that the Minister of Lands had refused a permissive occupancy to the Victoria Golf Club as he was opposed to allowing public lands being used for the convenience of a private club. The report indicated that the Minister had reached this position as a result of opposition raised against the golf club’s request. [10]

At a meeting of the Cheltenham Progressive Association the application of the Victoria Golf Club was discussed. A representative of the club indicated that they only wanted to use the requested strip of land in the event of an overflow such as happened on the opening day of the club when 250 cars were parked around the clubhouse. Other speakers supported the request of the club seeing the benefits Cheltenham derived by its presence. Mr Allnutt, a member of the Cheltenham Progressive Association who later became Shire President, pointed out that the club had put a gravel path through the park at their own expense, through a section that was previously impassable. In addition, he said the club’s policy was to spend money in Cheltenham. In his view it would be disastrous to Cheltenham to oppose the club. Cr Clements said that very few people took an interest in the park, and the club was prepared to beautify the old rifle butts by planting shrubs and flowers. The club already had spent £200 in one month in Cheltenham. He could not understand the narrow minded views of those opposing the granting of the land. It was then moved that the Association encourage the Victorian Golf Club in every possible way. The majority of progress association members present at the meeting supported this.

A second motion was them moved by Mr McCormick that the whole park and recreation reserve, excluding the football ground be turned into a nine hole golf course. Ken Whitehead seconded the motion with the proviso that it did not interfere with either football or cricket. He said he liked a game of golf but the paddock he used was only big enough for a two-hole course, a statement which caused a heightened level of merriment in the audience. [11]

On July 26, 1927 an enthusiastic group of men met at the Soldiers’ Hall in Cheltenham with the idea of forming a golf club in Cheltenham. The meeting recognized that very little could be done until the council agreed that a nine-hole course could be created in the Cheltenham Park. The meeting elected office bearers to the embryonic club. Mr McCormack took the role of president while K Whitehead was appointed secretary. Members of the club elected to the committee were Messrs Thacker, Jewell, Gleeson, McKenzie and Jones. [12]

The enthusiasm of the Cheltenham meeting did not carry across to the subsequent council meeting where a letter was read from the local Australian Natives Association Branch. The branch entered an emphatic protest against the alienation of the people’s rights in granting a portion of the park to the Victorian Golf Club. At the same council meeting a letter from the Cheltenham Progress Association was received asking “That the council use portion of the Cheltenham Park and clear it for the purpose of establishing Municipal Golf Links for the general use of the ratepayers”. In speaking to the request, K Whitehead, the author of the letter, stated that a club formed some years ago had cleared up a portion of the park for some such purpose and some improvements were then made to the park. In discussing the request Cr Claydon asked what would be the position if a school picnic were being held in the park at the same time as golf was in progress. He then moved that the association be informed it was the opinion of the council that the park could not be utilised for the purpose stated. It would, he said, interfere with other persons using the park, and he considered the recent outcry was sufficient proof that the people did not want the park taken up by golf. While supporting his colleague, Cr Stooke said there was a need to clear up the park but he agreed the park was not the place for golf. To the disappointment of the golf supporters the motion was carried. [13]

At a poorly attended meeting of the Cheltenham Progress Association, Cr Claydon, when faced with aggressive questioning by Mr McCormack concerning his position on the creation of a golf course in the park, said he was open to conviction, and if they could show him that it was possible to have a golf course in the park without interfering in any way, or liable to cause danger to anyone, he was willing to give it his support. Mr McCormack said a large meeting of ratepayers had wished it. The shire engineer and Mr Lennox had inspected and approved the site commenting it would not interfere with others using the park. McCormack considered it was the most progressive move ever made in Cheltenham, and would attract a good class of people. The council, he thought, should have given the proposal more careful consideration before rejecting it out of hand. For example, they might have referred it to the Minister of Lands. McCormack also questioned whether the councillors even knew what part of the park the golfers were requesting. It was, he said, a golden opportunity for the councillors to have done something for Cheltenham. To turn it down was an opportunity missed.

K Whitehead, the secretary of the budding golf club, wrote to the editor of the local paper in response to comments made by an earlier correspondent. He pointed out that very few people used the park except for tennis and cricket players. He did agree that parts of the park were unique with magnificent stands of ti-tree and other ornamental trees but the rest consisted of bracken fern, boxthorns, rubbish and other household discards. It only needed one burning match in the undergrowth and the ti-trees would be destroyed. He pointed out that cricket, tennis, and bowls, were already provided for, so he asked, “Why not golf?” He believed there was a misunderstanding of what portion of the park would be required and how much. At least four holes would be in the water reserve, and the other five in the south and southwestern portions of the park which was an eyesore. The club would clean up the area without interfering with the ti-tree and other valued shrubbery. He concluded his statement with the idea that by the time the park was used to such an extent as to make golf impractical the club would be in a position to seek “further fields and pastures new.” [14]

Alfred Pennington, an interested Cheltenham resident, responded to the comments of the golf club secretary about his earlier letter pointing out that he had once supported the idea of a golf club at Cheltenham but when he learned that at least forty acres of the park would be required he changed his mind. In his view no one club or sport should be allowed permissive occupancy of so large an acreage of a public park as would be required for golf. [15] A few months after the publication of Pennington’s letter news was received that permission to use a portion of the park as a golf links was granted. About 14 acres of the park known as the Water Reserve was involved. [16]

Shortly after receiving the welcome news, the committee of the club announced that subscriptions would be £1/1/- for gentlemen and 10/6 for ladies. The subscriptions set for young boys under the age of eighteen was 10/- while for girls the charge was 7/6. An enticement for people to join immediately was a chance to avoid an entrance fee. This opportunity would only remain open until a target of members was reached. [17]

In May 1929 the Minister of Lands, Mr Angus, together with officers in his department, visited Cheltenham with the object of assessing the justice or otherwise of applications from several groups wishing to excise parts of the park. One group sought land to site a scout hall while another wanted to extend an existing bowls club. The Minister agreed to both these requests. A third group, consisting of McCormack, Whitehead and Chandler presented the case for the Cheltenham Golf Club’s request for permission to play on the water reserve and a small corner of the park. The Minister was shown a plan of the course, and the general layout of the various greens upon which the club had already spent about £50. In addition, it was pointed out to him that members had voluntarily given a great amount of time in clearing and preparing the land. Mr Angus responded saying that he was impressed by their efforts in improving neglected areas and he would do all in his power to help them. However, he reminded them it was necessary to get the approval of the council and the trustees as he did not like overriding bodies in whom authority had been vested to manage the property. The club followed up his advice and approached the council for the necessary permission, which was granted, on the motion of Crs Clements and Allnutt. [18]

By early June 1929 twenty six individuals had joined but two weeks later the number reached was approximately 100. A meeting of members decided that the special concession of members joining without paying the entrance fee of £1/1/- would cease on June 17, 1929. At the same meeting the contractor preparing the course advised that the work of clearing and preparing the reserve for play was well under way and that within a couple of weeks members would be able to play on a portion of the course. However the warning was given to members that a little clearing still had to be done to “obviate the harassing experience of lost balls.” Members were also invited to attend the following three weekends with rakes, tomahawks or spades to clear the rubbish and fallen leaves under the ti-tree so there will be no lost time during play having to look for a lost ball. [19]

Work on preparing the fairways and greens proceeded steadily with the expectation that by the end of December or soon after all would be completed. Still there was one problem the committee had to face and that was wandering stock which damaged the work already completed. [20]

Fairways of Cheltenham Golf Club, 1973. Courtesy Eric Longmuir.

Almost five years later, in August 1934, a resident of Glebe Avenue, A Boyd, was writing to the local newspaper alerting readers to a proposal to remove trees and level a hill at the end of Glebe Avenue for the benefit of golfers. The trees themselves he claimed were a mere skeleton of the former abundant growth because of previous clearing. He called upon citizens to take whatever steps were necessary to stop the proposal. The time had come, he claimed, when a halt must be called to “sacrificing everything on the altar of sport to the detriment of the interests of the people as a whole.”

J J Whitehead wrote the following week supporting Boyd, pointing out that when the notion of a golf club was first raised with the Cheltenham Progress Association he warned that the club wanted an inch but it would not be long before they had the yard. Whitehead said the park was being filched from the residents to whom it rightly belonged and was being monopolised by the golf club which was composed mostly of “rank outsiders.” Acknowledging the improvements the club had made to the park he nevertheless thought it was time they were informed that they have no permanent right but only a permissive occupancy of the park. [21]

Other people joined the discussion. John Wilson accused the current administration of the park of mismanagement and asked where was the swamp that was formerly the haunt of reed-birds, gebes, wild duck and herons. Answering his own question he said the swamp had been drained and destroyed to make a “golfer’s holiday”. He said the park was rapidly becoming a sandy desert where birds and flowers that were familiar delights a few years earlier were no longer to be found. [22] Everest Le Page writing as chairman of the school committee viewed with alarm the proposed further encroachment of the Cheltenham Golf Club in the park. He wrote of the role the park would play as the district became more settled. Many native birds would find a sanctuary there just as the bronze wing pigeon had done. The pigeon was a bird that was becoming rarely seen outside the park. He went on to express a concern about the safety of students of Cheltenham State School and the danger they faced from flying golf balls. [23]

Club House of the Cheltenham Golf Club, 2006. Photographer Joe Astbury.

A visit to the park by councillors resulted in expressions of satisfaction of the work undertaken by the golf club. Cr Sheppard was astonished at the amount of work done by the club in improving the park and he saw the suggested work in the area of Glebe Avenue as another opportunity for improvement. Crs Butters, Allnutt and George supported the observations of Cr Sheppard while pointing out that a large portion of the park was still in its native state. [24]

The plan of the Cheltenham Golf Club to develop its course was implemented without further complaints being published in the local newspaper. No student from the primary school appears to have suffered injuries from flying golf balls but over the years some took the opportunity to provide themselves with pocket money by finding lost golf balls in the undergrowth and selling them to appreciative golfers.

Footnotes

- Victoria Government Gazette, March 24, 1863. Sellers, T., “Old Cheltenham Cemetery: A Brief History,” Kingston Historical Website.

- Charman Estate – sale of subdivision March 24, 1888 – Weatherall Road/Charman Road/ Mackenzie St/Coape St/Sydney St.Glebe Estate 21 January 1888 - 39 allotments.

- May 8, 1879 – Minute Book 4 Shire of Moorabbin.

- Council Minutes September 25, 1879 – Book 4.

- Council Minutes February 26, 1883 and Council Minutes December 23, 1889.

- See Kingston Historical Website – “Recreation Reserve” and “Cheltenham Bowling Club”.

- Lawrence, D., Victoria Golf Club 1903 – 1988, Playright Publishing 1988.

- Moorabbin News, July 9, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, July 9, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, July 16, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, July 16, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, July 30, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, August 6, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, August 13, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, August 20, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, October 1, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, October 8, 1927.

- Moorabbin News, May 25, 1929.

- Moorabbin News, June 15, 1929.

- Moorabbin News, December 7, 1929.

- Moorabbin News, August 25, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, September 1, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, September 1, 1934.

- Moorabbin News, September 8, 1934.