The Floods of the 1920s

The Carrum Swamp was a rich source of food for members of the aboriginal Bunurong tribe. The early surveyors who recommended that the area be made available for farming also recognized the richness of the soil. Provision for committing the swamp to agriculture was made in the 1869 Land Act. Those individuals who were successful in gaining a grant were immediately faced with the problem of too much water. The Dandenong and Eumemmerring creeks discharged their waters into the swamp from where the water gained inadequate access to Port Phillip Bay through Mordialloc and Kananook creeks. [1]

Norman McSwain, one of the early selectors wrote to the department of Lands pointing out the only way to improve the situation was through the provision of drainage. The Dandenong Roads Board and the Dandenong Shire made tentative efforts at drainage without any marked success. In 1872 those present at a public meeting agreed that all selectors would pay a levy towards a fund known as Drainage Fund of the Carrum Swamp Land. With this money some drains were constructed. Several channels were created to link the Dandenong Creek to the Mordialloc Creek and the Eumemmerring Creek to the Kananook Creek. In 1878 the Minister of Public Works, J B Patterson, recommended that a channel be cut through the sand ridge to the sea to allow the excess water to escape. The thirty foot wide cutting, which later became known as the Patterson River, completed in 1879, gave some relief but the problem was not solved.

Mouth of the Patterson River narrowed with silt, 1965. Courtesy Leader Collection.

In 1904 the Carrum Swamp was once again flooded. The Mordialloc Creek overflowed its banks, and a breakaway occurred in the banks of the Patterson River flooding an area 9 miles by 7 miles. Crops of potatoes were rotting in the ground, plantings of cabbages and onions were destroyed and stacks of hay were spoiled by soakage. Tenants holding up to 55 acres were unable to meet commitments of rent and rates, and there was no food for stock. They and their families faced a very bleak winter as other jobs were not readily available. Approximately three hundred families were affected. [2]

A severe storm struck the district in November 1922 causing residents to once again question the adequacy of drainage. Plate glass windows were blown in, fences flattened, and trees uprooted. The roofs of numerous outbuildings and poultry sheds were thrown into the air as though they were paper. The Mentone and Mordialloc piers suffered damage with planks being unfastened. [3] The drain, which carried storm waters from Cheltenham to the Mordialloc creek, caused flooding as it passed through Mentone and Parkdale. The damage it created caused considerable agitation amongst ratepayers. Over the course of years the course of the drain had been altered. In summer sewerage matter in the drain became offensive due to the lack of sufficient water to flush it out. Consequently it became a health hazard. Despite this the council was reluctant to commit any money to resolve the flooding, and the lack of flow at other times, as the Board of Works had indicated its intention to take over responsibility for the drain. [4]

On Friday , November 12, 1923 a phenomenal downpour of rain resulted in the Mordialloc Creek overflowing its banks causing extensive flooding. Water flowed through eight buildings in Chute Street to a depth of about one foot. Portions of Krone and Edith streets were feet deep in water while the Epsom racecourse was covered with three feet of water. Many of the roads were impassable. With the rupture of levy banks on the south side of the creek the area from there to Edithvale became covered feet deep in water. Acres of vegetable crops, chiefly cabbages, were ruined. The site of the proposed new high school was a swirling mass of water. This break in the banks of the creek relieved the pressure on the Mordialloc side. The Carrum end of the swamp suffered least and while the Patterson River rose considerably at no point near the town did it overflow its banks. Within twenty-four hours most of the water had disappeared. Land on the Epsom racecourse which was feet deep with water on Saturday by Monday had cows contentedly grazing.

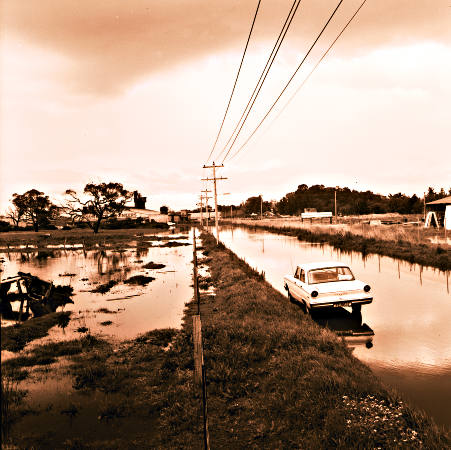

Flooding at Mordialloc, 1971. Courtesy Leader Collection.

While not all residents were personally inconvenienced by the flooding water there were annoying after effects. The myriad of frogs in the flooded areas set up a chorus of croaking early each evening and could be heard for some distance from their location. Golfers were denied their game of golf. The local newspaper, perhaps in a jocular fashion, reported that golfers were deliberating upon the advisability of forming a water polo team while waiting for the waters to subside. A large number of children took advantage of the situation to engage in water-based activities despite the presence of barbed wire, broken glass and thorns. Some bathed in the floodwaters rather than using the fine safe nearby beach. Pickets stacked at the Chelsea recreation reserve to be used to erect a fence instead became the material for boys “to construct rafts used to sail the inland sea." [5]

Dr Le Souef, the Borough Health Officer, asked the council whether anything could be done “to prevent floods and the consequent plague of frogs and mosquitoes together with the unsavoury aroma that results." Cr Beardsworth responded with a positive answer. He suggested the problem occurred because of bungling and incompetence and directed his spleen at the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission. The secondary drain, he claimed, was neither deep enough nor wide enough to do the work required of it. Its capacity was insufficient to handle the rush of water that occasionally occurred. Moreover, it was full of “debris of all varieties, overgrown with weeds and fouled with water grasses. Wire fences that crossed it were allowed to sag into the water catching the debris that was floating by." A deputation to the Minister responsible was required “to demand that the secondary drain be deepened, widened, and regularly kept cleaned, and free from all debris." [6] Cr Beardsworth reminded his colleagues that the district contained a wonderful asset in its agricultural section and they needed to look inland as well as to the beach. He warned that people would not continue to pay high drainage rates while at the same time risk losing valuable crops. [7]

Shortly after the council discussed the problem of flooding the State Rivers Department made an inspection of the area and undertook to carry out flood prevention work. Promises were made to improve the secondary drain so that it could cope with large future flows of water. Its entire length was to be dredged, banks built up and the drain widened at the Mordialloc end. Fences over the drain were to conform to a standard so that the full flow of water was not obstructed. Moreover, arrangements were to be made for the drain to be cleaned out regularly. Unfortunately, as “One Who Has Suffered by the Floods" pointed out, the improvements could not be undertaken until the flood waters that were covering a substantial area had disappeared. [8]

Heavy rains almost twelve months later once again caused flooding with disastrous results for many families. Again people were asking why this was happening. Frank Groves the local member of State parliament said it was the accumulation of ‘foreign’ flood waters coming down in large volume from the hill country which made it impossible for local drains to cope. A public meeting in the Wells Road hall attended by about 50 people asked Groves to arrange for a deputation to meet with the Minister of Water Supply to discuss a number of proposals including the fast tracking of the Hallam- Kananook Creek Scheme and the widening of the Eumemmerring Creek and subsidiary drains. [9] The Minister of Water Supply visited Carrum the next month to personally investigate the drainage question. After the inspection he said it was apparent that blunders of the past had contributed to the present condition of things, and it was the duty of the Government to give relief. He was very sympathetic and promised to place the position before his colleagues in cabinet. [10]

In March 1925 Councillors from the Borough of Carrum and the Shire of Dandenong, together with some of the Wells Road farmers, met with Dethridge and Conradi from the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission. Mr Dethridge pointed out that the drains had been cleared recently but the rushes and grass were again growing rapidly and were liable to check the flow of water. He thought it was necessary to allow cattle to feed on the grass and so keep it down. He also explained the option of enlarging the opening at the Mordialloc end to allow water further back to get away. Those present expressed the hope that the suggested work would be undertaken before the onset of winter to give some relief to those living on the swamp. [11]

The hopes of residents, councillors and members of parliament that the excess water problem would be solved so that in the future no family would face the damage to homes and the loss of crops was not to be realised. A massive flood in 1934 rendered more than a thousand people homeless. [12]

State Relief Committee providing clothing to victims of the 1934 flood. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

In 1952 about 1200 people were forced to leave their homes because of rapidly rising floodwaters between Aspendale and Carrum. [13] The local member of the State parliament, David Lean, announced in March 1999 that the problem of flooding would be beaten with the building of a Secondary Drain Pumping Station to disperse water from properties between the Mordialloc Creek and Patterson River. [14] So far the floods of the 1920s, 1930s and 1950s have not been repeated; rather more recently the concern has been the lack of sufficient water to maintain the bio-diversity of the natural areas of the Carrum Swamp.

Footnotes

- See articles: Nixon/Whitehead/Young/Comport on Kingston Historical Website, http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au

- Argus, February 1904.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, November 4, 1922.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, November 4, 1922.

- Moorabbin News, October 20, 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, Friday, November 9, 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, Friday, November 9, 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, November 30, 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, September 12, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, October 17, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, March 21, 1925.

- See Whitehead, G., Blowing a Storm in 1934 Article 212; Jones, Keith Neville, We were standing in it in 1934 - Article 132. http://localhistory.kingston.vic.gov.au

- The Herald, July 15, 1952.

- Community News, Patterson Lakes edition, March 1999.