Undesirables at the Beach Give a Town a Bad Name

Chelsea Beach c1980. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Back in the early 1900s Chelsea and its beach developed a bad reputation amongst some city folks. It was described as a place where people led a Bohemian lifestyle which often resulted in the break-up of families. In addition to these ‘permanents’ who gave the place a bad name there were the troublemakers amongst the ‘casuals’ who came down on the last train on Saturday night, known to some as the ‘drunk express’ to engage in orgies of drunkenness. Frank McGuire writes of this minority arriving after midnight with nine gallon kegs stacked in the rear train carriage and guard’s van. [1] It was these atypical behaviours that became associated with the name Chelsea, so some saw the easy solution was to change the name of the district. The thought was that if the name Chelsea was dropped the stigma associated with it would disappear. But people were to find the solution was not as easy as this.

At the Cheltenham Court, in August 1922, some aspects of life at the seaside camps were revealed when Myrtle Rose, of Aspendale, “a tall and bright looking woman" was charged with keeping “a house frequented by persons having no lawful means of support." Complaints had been received by the police of men staying at the place and consuming alcohol. The magistrate chose to dismiss the case saying there might have been immoral action taking place but there was no evidence of disorderly conduct. [2]

A few months later, in December, the Carrum Progress Association drew the attention of council to the undesirable characters who invaded the South Ward and other parts of the Borough during the weekends. “These noisy, foul-mouthed invaders" the Association claimed, were creating unjustifiable damage to property. What was required they believed was a by-law prohibiting owners from letting their premises to these undesirables. Cr Richardson said it was regrettable that residents for the sake of a few extra shillings let their houses to this class of individual in preference to decent citizens who would be an asset to the Borough. If the conduct continued, he believed, it was going to drive people away. Cr Hunter wanted the Chief Commissioner of Police to establish “flying gangs" of police to move around the district, particularly at the weekends, to quell unruly behaviour and act as a deterrent to offenders. Cr Boyd agreed that prevention was better than cure and wanted to see this scandalous behaviour nipped in the bud. Therefore he wanted to see additional police allotted to the district. Cr Beardsworth reminded his colleagues that it was only a minority of weekenders, young fellows, who became over-boisterous. The vast bulk of weekenders who came to the district were well behaved and they themselves had once been weekenders camping on the foreshore and enjoying the beach. [3]

Cr G R A Beardsworth, councillor and mayor of City of Chelsea. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

By June 1924 Cr Beardsworth was becoming tired of the constant and unwarranted stigma casted upon the Borough in the press because of events that had occurred in the distant past. It was a case of “give a dog a bad name it will always stick", he said. Newspapers were presenting Chelsea in the worst possible light. He did not see why slurs should be made upon their name and proposed to his council colleagues that a propaganda committee be formed to disseminate the best possible information about the town and to answer any unfair criticism. However, his move attracted no support from his colleagues so the proposal lapsed. [4] The local paper, the News, in reporting this suggested there was an immediate solution to this issue and that was to change Chelsea’s name. In support of its suggestion it quoted the success of Carnegie when it dropped its former name of Rosstown, a name that had attracted derision. [5] The News suggested that there was not one redeeming feature in the name Chelsea and that citizens who took a pride in the town should take immediate steps to select a new name and forward a petition to the authorities requesting a change.

Some ratepayers opposed changing the name for sentimental reasons while others wanted to get away from the unwarranted stigma placed on what to them was an ideal suburb. Mr Oliver saw a new name being the commencement of a new era for the town and one that people would not regret. Cr McGarry, W Fricke and the Rev E Durance argued that the town had made great progress under the name of Chelsea and changing it would not make any difference one way or another. [6]

The Carrum Borough Gazette, the alternative local paper to the News, was not so convinced that the name of Chelsea had to be changed to leave behind the “reputed unsavoury character of the early settlement of the locality." Its reporter thought the so-called ‘evil days’ had been grossly exaggerated in some quarters “causing hurt to sensitive people who were jealous of the good name of their town." More was required than the change of name. For him a change of character was necessary. To support his argument he referred to precedents in the Bible. Simon who vacillated and was unreliable became Peter the Rock, impregnable and the keeper of the keys of heaven. Saul the persecutor of the Church became Paul the Apostle of Jesus Christ. In these cases he saw the change in nomenclature denoting the change in character. The reporter believed Chelsea had changed beyond recognition over the preceding few years. There were strict regulations regarding behaviour on the beach, leaving no room for scandal. Gone were the many alleged hideous camps of drinkers. Those camps remaining were well conducted. Miserable ramshackle humpies had been replaced by comfortable homes complying with Council’s strict building regulations. Chelsea had been purged of all its alleged unsavoury elements. To support this conclusion he wrote of the relieving policeman who came to Chelsea expecting a ‘lively time’ but left commenting that he felt he had been to a Sunday School picnic despite the fact it was during the height of the summer season. [7]

Chas Sandforde had almost the last word in writing his letter to the Gazette. He said if the name was changed they would become a laughing stock for suffering from ultra sensitivity. Other towns suffer from reports in newspapers of fearful deeds being perpetrated but the city fathers did not suggest changing names. If changing names was to be “the action every time a cantankerous visitor barked then a permanent name changing committee would have to be established." For him visitors who engage in loutish behaviour besmirch their own characters and do not necessarily “affect the law-abiding citizens, who are generally speaking quite satisfied to retain the well known euphonious name of Chelsea." [8]

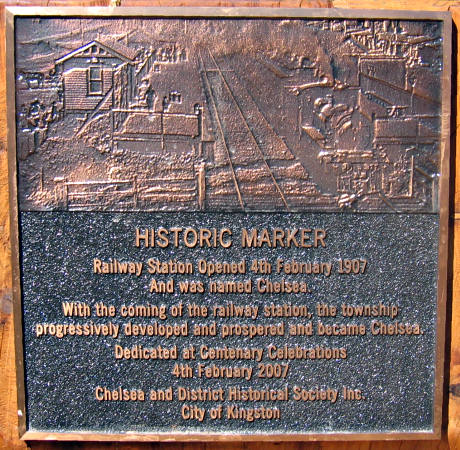

In 2007 the community celebrated the centenary of the naming of their railway station Chelsea. Over the years the agitation to the change the name dissipated and today the name Chelsea remains unchallenged.

Plaque outside the Chelsea Railway Station acknowledging the passage of one hundred years since the naming of the station. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Footnotes

- McGuire, F., Chelsea a Beachside Community, 1985.

- Seaside News, August 12, 1922.

- Moorabbin News, December 9, 1922.

- Moorabbin News, June 7. 1924.

- Moorabbin News, June 14, 1924.

- Moorabbin News, June 14, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, July 16, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, October 17, 1924.