Extending the Suburban Radius to Carrum

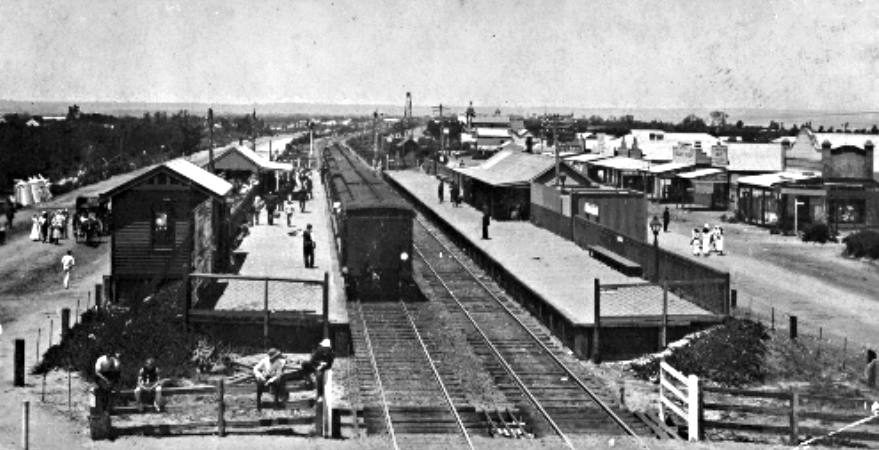

Chelsea Railway Station, c1910. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

In 1882 a single railway line extension was built from Mordialloc to Frankston with a siding being created at Carrum. This was followed in 1891 with a siding at Aspendale Park to provide access for visitors to the Aspendale Park Racecourse. Chelsea was created in 1907 followed by Edithvale in 1919 and Bonbeach in 1926. Each of these stations was described as a ‘Flag Station’ because intending passengers had to signal the driver of the steam train with a red flag to indicate their wish to board the train. Although the creation of these stations was seen as a victory by local citizens after long arguments with the Commissioners of Railways, their work was not finished. Frequency and timing of trains together with cost of fares remained sore points for some time.

The towns classed as suburbs had a different fare structure to the towns in the country and as far as the Railway Commissioners were concerned the difference related to distance from Melbourne. Those stations beyond a twenty mile radius from Melbourne were classified as ‘country’ while those within that radius were ‘suburban’. This meant that Edithvale and Chelsea were suburban and Bonbeach and Carrum were country. As a consequence there was a marked contrast between the fares paid for passengers embarking from Edithvale and Chelsea compared to those embarking from Bonbeach or Carrum. A second class ticket to Melbourne from Chelsea was 2/4 ½d while a similar ticket from Carrum was 3/6d; a significant difference of 1/1d. [1] Yet the difference in distance between those two stations was only 1 ¾ miles. The initial response was for residents of Bonbeach to walk to Chelsea to save the difference in cost. The solution to this unsatisfactory situation, according to the Carrum Council, was to extend the definition of ‘suburban’ along the line to Frankston, thereby allowing Bonbeach and Carrum residents to buy train tickets at the “suburban” rate.

Train at Sandringham Station, 1989. Courtesy Leader Collection.

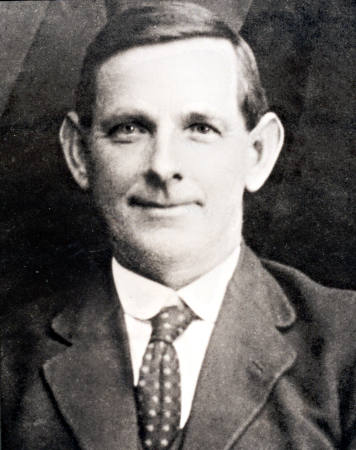

In October 1923 a conference of municipalities held in Melbourne passed a resolution that urged the government to extend the suburban area to include those districts whose natural progress was being inhibited by the imposition of the 20-mile rule. Delegates argued that many things had changed since ‘suburban radius’ was defined forty years earlier and these changes warranted the application of new criteria. Cr Beardsworth referred to the changes brought about by the electrification of the line and the fact that the progress of the township of Carrum was being strangled because of the excessively high fares. He pointed to the increase in outwards revenue from Chelsea of £3000, and from Edithvale of £1000 in contrast to the increase of £100 at Carrum and asked why the differentiation. He then proceeded to answer his question explaining that working men and business people living at Carrum would walk to Chelsea to achieve the benefit of cheaper fares. The resolution when voted upon was supported by approximately two hundred delegates with only three voting against it. [2]

Cr Roy Beardsworth. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

A deputation five months later, with representation from twenty three municipalities, met with the newly appointed Minister of Railways, Mr Eggleston, to argue the inadequacies of the twenty mile suburban radius and to protest against the excessively high fares. Politicians from both houses of parliament were present at the meeting. It was Frank Groves, the member for Dandenong, who introduced the deputation. In doing so he said there was an insistent demand for reform. Cr H Richardson, Mayor of the Borough of Carrum, said the conditions were stifling the development of two townships and he believed an extension of the suburban area would cure this situation. Cr Beardsworth supporting the statements of the mayor pointed out that when young people started work the family fare bill was unbearable and as a consequence the family moved back into the crowded inner suburbs to save the expense of the fares. He said the railways were a great public utility and should be made first to serve the people and then look for profits later in the service. Speakers from other municipalities spoke in support of the previous speakers. Cr Clements from Moorabbin said he frequently had to go to Frankston but the fares were too much, “so he consulted Henry Ford and found him cheaper.” [3]

The Minister promised he would give fresh consideration to the matter without referring to earlier files or deputations, acknowledging that the deputation had put up a strong case. Where electrification had reduced travel time it seemed fair that something should be done, he suggested. Thus he was prepared to consider a partial extension to the suburban radius in situations where the lines were electrified. This was at variance with the views of Mr Clapp, the Chief Commissioner of Railways, whose position was “all or none.” However the Minister warned that in his role as Assistant Treasurer in the Liberal government he must consider the financial cost, as a keynote of their administration was sound finance. The deputation members were happy with the Minister’s response as it suggested a way forward. [4]

Three months later Minister Eggleston responded to members of the deputation pointing out that an increase in the suburban railway radius from 20 miles from Melbourne to 30 miles would double the total suburban area and would take in large areas of land which were not likely to develop in any significant way nor attract additional traffic. As a consequence he urged the railway commissioners while not increasing the suburban area all round to take certain lines that were capable of development. However the commissioners, he indicated, were averse to acting on this suggestion. Nevertheless he thought there was every prospect of the Frankston and Dandenong lines being included. [5]

By October of 1924 Mr E Hogan who replaced his colleague Mr Eggleston (Nationalist Party) as Minister of Railways provided a copy of a lengthy report from Mr Clapp to Mr Eggleston in which it was argued why the suburban radius should not be extended. While agreeing that suburban development had occurred in some places outside the twenty mile radius he had grave reservations about the consequences of extending the suburban conditions to such places without giving the similar treatment to other stations the same distance from Melbourne. Principally he believed it would create anomalies in regard to country travel which would probably arouse wide spread discontent among country residents. For this reason he believed any extension of the suburban radius should be uniform. His final point was that financial circumstances of the government did not permit any moves on the matter. [6]

June 1927 saw a new Minister of Railways, Mr Tunnecliffe, in a government formed by the Australian Labor Party, telling a deputation from the Borough of Carrum and the Shire of Frankston and Hastings that extending the radius was a big problem. However, he would discuss with the commissioners the extension of cheap fares to places where there was a tendency toward closer settlement. To explain the issue Cr Boyd of Carrum informed the Minister that his council had introduced a bus service from Carrum to Chelsea. Workers by using the bus saved 7d on a return daily fare in comparison to using the train from Carrum. He also claimed that thousands of people would come to the district from the inner suburbs ensuring that the railways would have greater revenue than before. Cr Beardsworth argued the government should be encouraging the implementation of cheaper fares to the seaside suburbs in the interest of the health of the workers and their children. [7]

The councillors of the south ward of the Borough of Carrum kept agitating for an extension of the suburban radius but without success. The Premier and a former Minister of Railways, Mr Hogan, refused to accept a deputation and Mr Clapp maintained his stance. For him no individual line would receive a radius extension unless it was applied to all lines. A reporter on the Carrum Gazette posed the question, “What would Sir Thomas Bent have done in a similar situation? Would he run the Commissioners, or would they run him?” [8] As the Premier had expressed on five separate occasions that he would not meet with a deputation, the Carrum councillors, twelve months later turned to the Leader of the Opposition, Sir William McPherson, seeking his support. Sir William indicated that he agreed with the views of the deputation, “that the suburban area should be extended wherever progress warranted it,” but unfortunately he was not at that time in a position to “promise any redress.” [9]

In July 1928 representatives of the Carrum council met with the members of the Railway Inquiry Commission to present evidence on the question, “Why the Railways Do Not Pay.” Cr Bowman, Mayor of Carrum, informed the commission that the Borough would shortly be proclaimed a City and reminded them that residents of Bonbeach had subscribed £500 towards the cost of creating the station on the understanding suburban fares would be charged. Bonbeach he pointed out was only ¾ miles from Chelsea, suffered the disadvantage of the country fare scale, yet together with Carrum was valued for rating purposes as if it was suburban. In response to a question from the commission regarding the bus service from Carrum to Chelsea Cr Bowman said it was no longer operating as the Country Roads Board prohibited it. The majority of those passengers who had previously made use of the bus to travel from Carrum to the Chelsea railway station, thereby saving a considerable amount of money each week, did not use the train service from Carrum to Chelsea in place of the bus. Instead they walked the distance so the railways did not reap any benefit from the loss of the bus originally introduced by the council to help the ratepayers living outside the twenty mile limit. As a result of the evidence placed before it by innumerable witnesses the Railway Inquiry Commission recommended the extension of the suburban radius on the Frankston line. [10] But its implementation still remained with the government and the railway commissioners.

By the end of 1928 the government had changed. Sir William McPherson was now the Premier and Frank Groves the local Member of Parliament, an original member of the first Carrum Council and an advocate for some years for the extension of the suburban radius, was now Minister of Railways. The councillors quickly sought a deputation with the new Minister but were advised that he wanted to consult the Commissioners before he received them. The council, perhaps anxious and irritated after years of inaction, replied asking him to expedite the matter. The Carrum Progress Association received an answer, from the Minister’s secretary in March 1929, to their correspondence in which they expressed hope that the present ministry would grant the long overdue extension to the suburban radius. The answer simply said that the Minister had for some time been discussing the matter with the Railway Commissioners and they would be advised when finality was reached. [11]

Frank Groves, Member of Parliament. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

In April 1929 the requested interview with the Minister of Railways occurred. Frank Groves received the deputation from the municipalities of Carrum and Frankston and Hastings and indicated his long-standing interest in the extension of the suburban radius to include the Frankston line. Members of the delegation quickly reminded him of the reasons why the extension should be granted. They pointed to the recommendations of the Railway Inquiry Commission, an unbiased body, and the fact that many residents walked to the Chelsea station to catch a train, as they could not afford to pay the designated fare. The population of Carrum was dropping and the attendance at the local school was decreasing. Groves said he would personally urge the government to grant the extension sought. The deputation thought with the cheaper fares the district would develop and generate additional revenue to compensate the loss the railway commissioners expected if the concession was extended. The deputation retired feeling that they had won their case and together with the Minister’s support expected the government to grant their request. [12]

Three months later residents were still waiting. When Frank Groves, the Member for Dandenong, became Minister of Railways they thought the extension of the suburban area to Frankston was a certainty but by July they became anxious. Nothing had happened and the position of the government was insecure. The local paper suggested their local member should seize the occasion and fight for the extension even if he suffers defeat at the hands of his parliamentary colleagues. [13] Cr Boyd said the people of the South Ward were rated and taxed on suburban values yet were tied down to country conditions regarding railway transport. It was an intolerable situation and one they could no longer tolerate. [14]

In December 1929 Sir William McPherson’s government lost power. Edmond Hogan a former premier returned to form the new government. Frank Groves lost his position as the local member for Dandenong and was replaced by H Cremean who during the election campaign pledged to work for the extension of the suburban radius to Frankston. In his speech to the House of Assembly Cremean addressed the issue of the extension presenting once again the iniquitous system, adopted many years earlier by the Railway Commissioners, which caused passengers from Carrum to pay a significantly inflated fare because they were classified country. [15] The second class fare from Chelsea to Melbourne was two shillings and four pence one half penny while the fare from Carrum for the extra 1 ¾ miles was three shillings and six pence.

March 1930 saw a visit to the Chelsea municipality by the Minister of Railways, Mr John Cain MLA. Once again the facts of the situation were presented to a Minister who in turn flattered the councillors with praise but promised nothing. Cr Boyd in presenting the case indicated they were getting weary of the fight. Cr Beardsworth supported the arguments presented by Cr Boyd explaining that people who lived at Bonbeach and Carrum were people who came from the industrial suburbs and had to go back there daily to work. They had come to live at Carrum to gain a cleaner atmosphere for their children. It was very hard for many of these people to have to tramp to Chelsea to avoid paying the high fares. [16]

Four months later Chelsea councillors were struggling to get the Premier and the Minister of Railways to receive a deputation. They were aware from a report published in The Argus that the Railway Commissioners had to cope with an operational deficiency of over one million pounds. [17] This had occurred because of a decline in patronage, increased costs due to additional interest charges, the need to provide for superannuation, the payment of higher wages and escalating costs of materials. The blame for the deficit, Cr Boyd said, lay with the Railway Commissioners because of their stand and deliver policy. He recalled the past when Commissioners had provided incentive, such as free passes, to people to encourage them to patronize the railway system. No longer, he said, were incentives offered to make railways an attractive medium of transportation. People were being forced to live in the inner suburbs to avoid the crippling fares. [18]

Towards the end of 1930 councillors and residents were confident that the government would listen to their arguments that the definition of the suburban area should be extended to include all the City of Chelsea and take action to implement the decision. However this did not happen. No doubt the railway commissioners viewed the possible loss of revenue, the implications for other lines and the rising costs of running the system as deterrents to adopting the proposal at a time when the economy was experiencing deep depression.

Up until and including the twenty first century distinctions were made between several groups of stations on the Frankston line. In February 2007, the Mayor of Kingston, Cr Petchy welcomed the decision of the train operator, Connex, to abolish the Zone 3 category thus presenting travellers in that zone with a savings of almost three dollars on a daily adult ticket to the city. [19] For Cr Petchy a significant gain was that railway patrons would no longer see it as being necessary to drive their cars to Carrum to gain Zone 2 prices and thereby creating congestion difficulties and exacerbating parking problems. [20]

Footnotes

- Carrum Borough Gazette, June 25, 1927.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, October 19, 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, March 28, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, March 28, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, June 13, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, October 17, 1924.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, June 25, 1927.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, October 22, 1927.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, June 2, 1928.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, November 2, 1928.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, March 9, 1929.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, April 6, 1929.

- City of Chelsea News, July 27, 1929.

- City of Chelsea News, September 14, 1929.

- City of Chelsea News, January 11, 1930.

- City of Chelsea News, March 8, 1930.

- The Argus, July 5, 1930.

- City of Chelsea News, July 19, 1930.

- Full fare adult Zone 3 tickets to the city were reduced from $12.60 to $9.70.

- Mordialloc-Chelsea Leader, February 26, 2007.