Second-Hand Houses at Chelsea and Edithvale

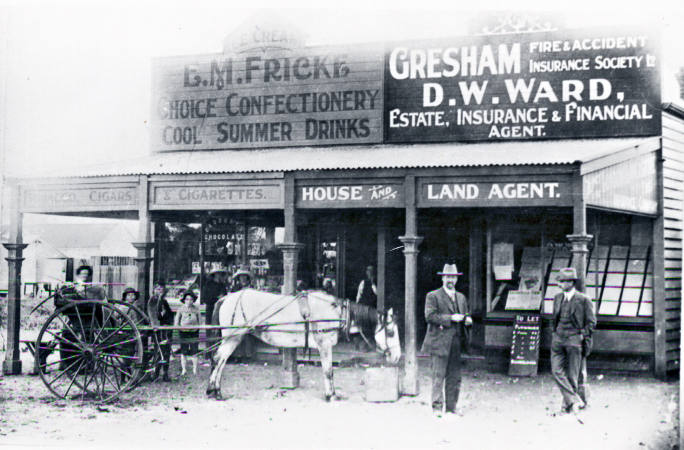

Two “second-hand” shops resited on the corner of the Walkway and Point Nepean Road, Chelsea. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

In the early 1900s Melbourne families travelled down to the Chelsea district for holidays, camping under the foreshore ti-tree. Here they benefited from the pristine conditions: clean air, the crystal clear water, miles of fine white sand and the opportunity to fish. Further inland shooting was possible, with the prevalent wild life on the extensive Carrum Swamp.

Many, recognizing the beauty of the location, decided to take up residence in the district, purchasing small parcels of land and erecting houses. Some of these earlier homes, rather than being constructed on the site, were carted from suburbs closer to Melbourne. By the early 1920s, these ‘second-hand’ houses were a topic of discussion at the newly created council of the Borough of Carrum.

In 1923, a wooden building, estimated to be forty years old, was the centre of a local protest when it was ‘dumped in the midst of the coast’s Toorak foreshore’. [1] The local newspaper supported the practice of bringing in houses, provided that they were brought up to standards satisfactory to the Council, including the renewal of joists, weatherboards, flooring, ceiling and rafters. This was not satisfactory to Cr Hunter. He wanted the building regulations amended to prevent any existing building being moved from another district and brought into the Borough of Carrum. He argued that most of these houses were brought in by speculators who splashed a bit of paint on them to cover the faults and then sold them to unsuspecting individuals. Cr Beardsworth agreed. While acknowledging the houses were bought cheap, by the time the required modifications were carried out he believed it made them dearer in the end. He was also concerned about the diseases and vermin that were also brought in at the same time. Cr McGarry was also a supporter of banning second-hand houses. In his view second-hand houses destroyed private enterprise and aided the speculator. [2]

Other councillors were not convinced by the arguments of Hunter, Beardsworth and McGarry. Crs Rigby, Boyd and Gollen quoted instances of substantial buildings – assets in the community – being brought into the municipality. Rigby thought it ridiculous to impose regulations that would be a hardship those people who could not afford to lose an opportunity to secure a home at a cheaper rate. When asked for his opinion the building inspector said it was impossible to assess the condition of a building until it had been stripped and removed. The issue was put to the vote: five councillors voting against prohibition, four voting in favour. [3]

Two weeks later, protests were once again heard. A very old and dilapidated structure was brought into an area of Edithvale, determined to have ‘a fine class of residence, many in the course of construction.’ Its placement there was said to be disheartening to adjoining and surrounding property owners, as it would seriously depreciate the values of their properties. A call was made to the Council to make an inspection of the house in question before its faults were obliterated with paint. [4]

Within a fortnight Cr Beardsworth reiterated his earlier concerns, moving in Council that ‘ . . . as the imported second-hand houses were a menace to health and detrimental to the best interests of the district, as well as being more costly than a new house to the subsequent owner, that the importation of second-hand houses to the Borough be prohibited’. In the Council Chamber Beardsworth displayed rotting and borer infested timber taken from a house bought for £40 and recently relocated to Bristol Avenue at a cost of £75. The response from Cr Gollan, a builder by trade, re-affirmed his opinion that some second hand houses were preferable to new buildings and suggested, from his building experience, that the timber produced by Beardsworth was dry rot. This Beardsworth denied. Cr McGarry maintained his opposition to second-hand houses, saying that there were quite enough decrepit houses in the Borough of Carrum , without bringing in dilapidated houses from other parts. The move by Beardsworth was again defeated with a vote of five to four. [5] Nevertheless Beardsworth was not satisfied; his last words on the subject being: ‘A question is never settled till it is settled right.’

Footnotes

- Carrum Borough Gazette, 9 March 1923.

- Moorabbin News, 6 October 1923.

- Carrum Borough Gazette, 12 October 1923.

- Seaside News, 27 October 1923.

- Moorabbin News, 10 November 1923.