William Jones Singleton: Pioneer Minister

The Reverend William Jones Singleton. Courtesy Peter Allard.

Parishioners, friends and relatives were shocked at the news of the death of the Reverend William Singleton. He died at 8.30 on Sunday morning 13 June 1875 at his home in Victoria Street, Brighton, while preparing to attend services of that day. [1] [2] He was 71 years of age. The Bishop of Melbourne, the Right Reverend Charles Perry, appointed him as the first vicar of St Matthew’s Cheltenham and placed him in charge of the infant churches of East Brighton, Mordialloc and Gipsy Village. [3] His first appointment in Victoria had been to Christ Church, Kilmore. His death brought to an end 34 years of service as a minister in the Anglican Church, and 26 years as a pioneer in the colony of Victoria at a time when Europeans had barely established themselves, and he served through the crazy development and population explosion following the discovery of gold in 1851.

Some of the Cheltenham congregation were aware of the scarcity of clergy in Melbourne. Few were available to become their vicar. Many Church of England communities had to rely on lay readers to conduct Morning and Evening Prayers with the occasional celebration of the Lord’s Supper by a visiting priest. Bishop Charles Perry, as the first Anglican bishop of Melbourne, was reluctant to ordain men who had not achieved a high standard of education, preferring to rely on laymen and deacons to conduct services in communities throughout Victoria. Clergy were in short supply and stipends could not be guaranteed in the thinly spread and sparsely populated communities. [4]

William Singleton was well qualified. He had graduated BA in 1826 from Trinity College Dublin as a student paying annual fees, and later was awarded an MA (ad eundem) in 1867, without examination, from the barely established University of Melbourne. [5] His earlier education had been at the school of Mr von Feinagle which was principally known for its emphasis on the exercise of memory, an approach that was in vogue in Dublin at the time. [6] When thirty six years of age Singleton was ordained deacon at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, on 28 November 1841 by Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Tuam, Killalla and Anchonry, and subsequently was ordained priest in the Church of Ireland. Later he was appointed curate to the church of St Canice in the parish of Finglas where Dr Robert Walsh was the rector, a man with a fine reputation as preacher, scholar and priest. [7] However, Singleton had difficulty providing for his family of nine children at that time on a meagre curate’s stipend and actively sought from the Bishop of Melbourne’s commissioners an appointment to a parish in the colony of Victoria. [8]

Prior to his ordination in Dublin he married Frances Truelock in that city on 11 October 1834. For a time after their marriage Frances and William lived near Bray at Valetta in the county of Wicklow, in a house built with her money. There several children were born. Frances came from a family with wealth and social connections. Her father William Truelock was a native of Connaught and a noted small arms manufacturer. Her mother was Georgina nee Gratham. [9]

William himself came from an Anglo Irish family whose ancestors originated from Lancashire and settled in county Clare in the 17th century after leaving Cromwell’s England. Singleton descendants believe their family can be traced back to Quinville Abbey in the parish of Quin. [10] William’s father, also named William, was a prosperous merchant in Dublin. His mother, Mary Quinn Lewis, was a member of a successful family with many members in the legal profession. Others served in the army, the church and the public service in Ireland, Britain and overseas. [11] The Reverend William was the eldest of eight children, born to William and Mary, two of whom were later to join him in the infant colony of Victoria. [12] John, one of William’s brothers said their parents were strictly moral and brought up their large family with tenderness and wisdom and described the occasion when their father ‘administered timely and judicious correction’ to himself and an older brother for stealing cherries from a neighbour’s garden. [13]

Crest of the Singleton Family. Courtesy J Inglis.

In 1845 Ireland was hit by a major disaster. The potato crop failed, a crop upon which the bulk of the population depended for food. Repeated failure of the potato crop over the next six years decimated the population. There were unprecedented levels of death. Records show that over one million people died and two million fled the country. The small landholders had no security and relied on the nutritious potato to survive. Disease was rife. Typhus fever, typhoid, dysentery, diarrhoea and smallpox took the lives of many people. In addition, earlier in the 30s, the tithes imposed legally by the Irish Anglican Church on land occupiers regardless of religious persuasion increasingly came under attack. It was bitterly resented as an unfair tax by the much more numerous Roman Catholic population, many of whom refused to pay the tithe. As a consequence, in some counties, Anglican clergy received little or no income and the number of bishoprics was reduced in order to maintain viability. [14] These factors, spread over a decade, no doubt reduced the opportunity for William Singleton to advance himself in an Irish parish and this together with a growing family probably encouraged him to seek a church position in the colonies.

The Singleton family of twelve sailed from Plymouth on the Tasman on 11 July 1849 sharing a cabin with six other passengers. William was noted in the shipping records as being a religious instructor with the cost of his passage being partly defrayed from the ‘Public Fund’. [15] The ten Singleton children ranged in age from thirteen to two years. [16] Arriving at Geelong on 28 October 1849 they were met by John Murphy, merchant, to whom they had letters of introduction. On 15 November 1849 the bishop appointed William to the new parish of Kilmore, the largest inland town in Victoria, and it was there that William Singleton took up the incumbency in January 1850 and remained for almost eighteen years. [17]

The journey to Kilmore would have been a continuation of the adventure the Singletons embarked upon since leaving Ireland. Mr Hales, a fellow Irishman and graduate from Trinity College Dublin, arrived in Melbourne eighteen months before the Singleton family, to be appointed to Gippsland. While his wife remained in Melbourne Mr Hales set out for his parish with a guide. He describes his equipment for the journey as Strong trousers, waistcoat, and waterproof frock coat, the shirts of which I was obliged to tie out of the way, a pair of shoes, leather gaiters and spurs, a straw hat fastened to me with a black tape. My luggage was a pair of saddle bags containing 3 shirts, 5 pairs of socks, 3 white cravats, a night shirt which gave me a pleasant change at night, and a night cap to wear in the bush. My journal, memoranda, and a few papers, small portfolio with Francespaper, a few sermons of my own, hair brush, razor, comb, nearly a pound of tobacco, which Dr Adam kindly gave me as ‘bush money,’ my pocket bible. I had beside thread and needle, matches, a large bush knife, some soap, and a piece of wax candle which at Dr Adam’s suggestion, Mrs Wilmot gave me. [18] Like Hales’ journey to Gippsland, Singleton first went to Kilmore accompanied by a guide but in his case the guide was the Rev Daniel Newham, the Bishop’s chaplain. Singleton went to establish the state of affairs at Kilmore and to see whether he could procure any temporary accommodation in the village or neighbourhood. [19]

William Singleton was not the first Church of England clergyman to visit Kilmore as the Rev Adam Compton Thomson conducted the first service there in the forties. Bishop Perry himself visited Kilmore with his chaplain on 6 May 1848. However, William was the first clergyman appointed to the new parish, a parish which stretched an immense distance from the Murray River to Melbourne. [20] The Church of England Messenger of 1850 reported that a brick school room had been opened for public worship on Sunday 17 February 1850 and the Singleton’s were in residence in an attached dwelling. The Messenger also reported that it was the intention to increase the gentleman’s accommodation by the addition of two rooms. An earlier reference indicated that William had a tent that would have helped to accommodate his large family. [21]

Church and parsonage of Christ Church, Church of England, Kilmore, c1864. Courtesy J Inglis.

Shortly after arriving in Kilmore, William started conducting services throughout his extensive parish, alternating weekly services in Kilmore with other locations and through these efforts the foundations of the churches in Kilmore and Broadford were laid. [22] At Kilmore he was involved in the community, serving on the committee of the Benevolent Asylum and as an ex-officio member of the Mechanics’ Institute’s committee. Of genial and affable manner, he was judged to be a ‘good citizen, very popular and generally well received in the homes of the squatters and the more humble dwellings of the shepherds. As a visitor he excelled and those who were missing from their pews on Sunday were certain to receive a visit from him on Monday morning. As a preacher his efforts were rated as moderate but his sermons were carefully thought out expositions of passages from the Bible always presented in an evangelical and practical way. … He made no pretensions to oratorical display.’ [23]

Interior of Christ Church, Kilmore. On front wall to the right is a memorial plaque to the Rev William and Frances Singleton, 2009.

Frances, being an accomplished horsewoman, accompanied William on many of his journeys throughout the region. Her daughter said ‘she could ride twenty five miles before breakfast and another twenty five afterwards and still be fresh and chatty.’ [24] In addition to supporting William in his work as a minister of religion Frances had the care of eleven children, the last of whom was born at Kilmore. The boys rather than attending the local school had a tutor with whom they studied until two o’clock in the afternoon. After that time they worked outside, in a situation described as recreation. With the discovery of gold Kilmore saw the influx of many people drawn from a range of occupations, social classes and cultural backgrounds. Mrs Singleton was concerned to protect her children from what she saw as morally corrupting influences from this invading group of ‘doubtful characters’. Moreover, she wished to discourage them from venturing to the gold diggings. [25] This latter concern was not avoided as several of her sons went gold prospecting and achieved startling success. Singletons were involved in the discovery of the reef that became the Royal Standard mine at Wood’s Point, allowing them to amass a considerable fortune. [26]

Frances Singleton. Courtesy Peter Allard.

In 1867 the Singletons moved to East Brighton with William being appointed incumbent at Cheltenham and minister in charge at East Brighton, Mordialloc and Gipsy Village. These congregations had previously formed part of the parish of St Andrew’s Brighton under the charge of the Rev Samuel Taylor, a fellow Irishman and friend, both being graduates of Trinity College Dublin, although at different times. Mrs Lachlan Smith, a granddaughter of William Singleton and Samuel Taylor said ‘Grandfather Taylor was pleased to welcome Grandfather Singleton and for him to take over a portion of his very large parish which had a growing population in an area twenty years earlier was bush.’ [27] [28]

The Church of England had been in the district before the 1841arrival of Dendy and the creation of Brighton. As the land beyond the Dendy selection was subdivided and sold by auction in 1852 new congregations were formed. These congregations were served, in the main, by lay readers with the occasional visit of a clergyman. [29] At Cheltenham, members of the church had been meeting in two schools, one at Spring Grove and the other in Silver Street and for a time services were conducted in the Mechanic’s Institute, but by the time of Singleton’s arrival a brick church had been erected. Rev Samuel Taylor and Canon Perks preached at the first services in the new church named St Matthew’s on 14 April 1867. At East Brighton (Bentleigh) divine services had been conducted at St Stephen’s, the Common School, since 1 February 1850. [30] At Mordialloc services were also conducted in the National Common School building. The school was opened on 6 January 1868 and it was there on 5 July in that year that the earliest known Church of England service was conducted by lay reader William Robert Looker. Services continued at the school until 1874 when they ceased because of complaints that the children’s desks were being damaged. For a time the congregation met in a tent. The weatherboard church was opened in 1874 with Dean McCartney preaching at both services of the day. [31]

William Singleton and his family after leaving Kilmore took up residence at Framley in Jasper Road, East Brighton. From there he commenced his work with the various congregations. At East Brighton on 17 September 1866 the committee of St Stephen’s (later becoming St John’s) discussed the steps that needed to be taken to support a curate. [32] At Cheltenham the local committee canvassed the members of the congregation in April 1867 to raise the money to engage a minister. At that time the church’s prime method of financing its activities was through pew rents. Individual families paid an annual fee for the use of a particular seat in the church each time there was divine worship. Where additional money was required for building construction or maintenance, or purchase of furniture, operation of a Sunday school or payment of ministers, appeals were made to the congregation. The appeal for money to employ Rev William Singleton at Cheltenham was successful but finding sufficient money for his stipend remained a problem for many years. The Cheltenham committee wrote to the East Brighton committee on 2 May 1867 requesting a conference to establish the respective times of the minister’s ministrations in the two churches. The Cheltenham committee wanted the Rev Singleton to conduct morning services on every alternate Sunday. The request was accepted by the East Brighton group provided that on those Sundays the Rev Singleton took the evening service for them. At the beginning of 1868 the East Brighton congregation was able to inform William Singleton that forty pounds had been raised towards his stipend. [33] In May 1868 the reverend clergyman wrote to the Cheltenham committee seeking clarification of what portion of his stipend they would contribute. Given this information, he informed them, he would then be able to allot his services accordingly. [34] Later in that year he was informed that fifty pounds would be subscribed towards his stipend. [35] In 1871 the congregation was informed by the Bishop that additional money had to be found for the clergy stipends as State Aid to the churches was being withdrawn. Additional money had to be found to cover the deficiency. [36] By April Singleton was told that the committee had received promises to cover the amount of £20. Four years later the Cheltenham Committee was writing to the Mordialloc congregation seeking a meeting to establish what portion of the clergyman’s time should be devoted to them and hence the amount of money they would provide toward his stipend. Mordialloc responded that they were not willing to contribute anything to the clergyman’s stipend. [37] During the latter years of William Singleton’s incumbency at St Matthew’s raising money for his stipend continued to be an ongoing problem and payment was often tardy. [38]

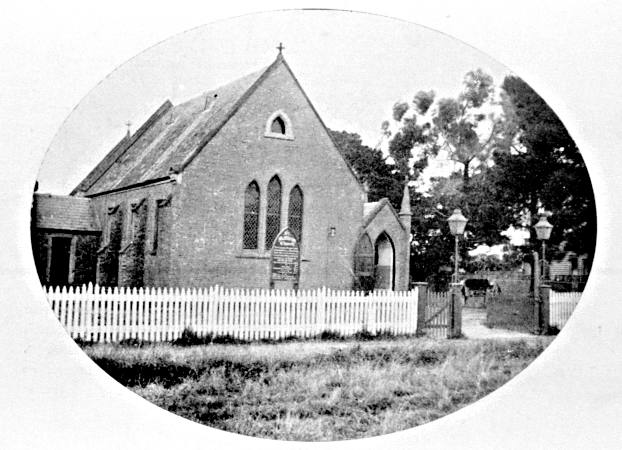

St Matthew’s Church of England, Cheltenham, c1920. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

On William Singleton’s arrival in East Brighton one of the first tasks the committee asked him to address was the behaviour of young men and children during church services. He was requested to speak to them. [39] At Cheltenham a running sore was the future of Cheltenham School No 127 in Silver Street. The Church of England school at Spring Grove had been closed in 1860 but Silver Street School under Miss Gott continued. However, the Board of Education was desirous of amalgamating many of the small schools that existed in close proximity to one another. The Wesleyan school, Beaumaris No 84 was operating in La Trobe Street. The Rev Samuel Taylor, vicar of St Andrew’s Brighton, was the school correspondent for No 127 and he wrote to the Board in January 1867 arguing that the two schools should not be joined, referring to a promise of the Board that if attendance numbers were maintained they could continue with government support. However, the Board changed its mind and directed that the two schools should amalgamate on a new site adjacent to the Cheltenham Cemetery. Taylor pointed to the large number of young children, under the age of seven, who would be shut out from education because of the increased distance they would have to travel. In addition, such an amalgamation, he suggested, would be decidedly injurious to the religious well being of the children of the locality. An earlier attempt at amalgamating the Spring Grove school and Wesleyan school had failed. [40] On his appointment to Cheltenham William Singleton took up the role of correspondent for School No 127 and again argued the case for the Cheltenham school. Writing from his home Framley, in Jasper Road, East Brighton he reminded the Board that the school had always been conducted efficiently. Inspectors had always reported favourably on its operation. He also raised the issue of distance between the homes of the pupils and the location of the amalgamated school. He wrote that three fourths of the pupils attending Cheltenham No 127 lived to the East of the school house and would have to walk a considerable distance passed it to get to the new school. In his view, an unsatisfactory situation. [41] However, his support for the Silver Street school did not have any effect.

By 1870 the Preachers’ Book at St Matthew’s shows that Singleton was regularly taking either morning or afternoon services each Sunday at Cheltenham. Two years later lay preachers start to appear occasionally. The lay preachers included Hearle, Looker, Budd, Smith and Booker. Two services on a Sunday commenced in 1874, one in the morning and other in the evening, with Singleton being involved in both. On 13 June 1875 the Reverend William Singleton died at his home Pellew House in Victoria Street, Brighton from a ‘rupture of the heart and natural decay’. He was aged 71. [42] He was buried in the Melbourne cemetery, ‘borne to his grave by seven sons’. [43] The service was conducted by the Dean of Melbourne and the Reverend Samuel Taylor.

Frances outlived her husband by almost fifteen years. At the time of her death on 9 May 1890 she was living with her daughter in High Street, Armadale. [44] Her death at 82 from ‘deficient heart action’ was certified by her brother-in-law Dr John Singleton. [45] The congregation at Cheltenham learned of her death with sadness and placed a memorial plaque to both her and her husband on the wall of the sanctuary of the church.

Plaque in memory of the Rev William Singleton and Frances is wife, in the old St Matthew’s Church, Cheltenham. Courtesy Dennis Maynard.

Footnotes

- Victoria, Births Deaths & Marriages, The Argus, Monday, 14 June 1875.

- A plaque on the wall of the original parish church of St Matthew’s Cheltenham indicates that William Singleton died on Sunday morning 14 June 1875 and S. Polites in the history of the parish, Pioneers of Faith, writes that he died while conducting a service in the church. However the Death Certificate gives the date of death as 13 June 1875 taking place at Victoria Street, Brighton.

- Documents vary as to the nature of his appointment. His obituary in the Church of England Messenger notes he was incumbent of the parish of East Brighton while other sources list Cheltenham as his cure.

- Holden, C., Church in a Landscape: a history of the Diocese of Wangaratta, page 13.

- William Singleton was admitted to the degree of Master of Arts at a conferring ceremony held on 17 April 1867, Academic Reports University of Melbourne. www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/archives/exhibitions/keys/049.html

- Leslie, J. B. Clergy of Dublin and Glendalough, 2001.

- St Canice was abbot and bishop of Finglas c560.

- Singleton, John Narrative of Incidents in the Eventful Life of a Physician 1891.

- Singleton, Margarita W. A Short Account of the Family of the Late Frances Singleton, Wife of the Rev William J Singleton, 1903.

- Inglis, J., Kilmore Connections, Kilmore Historical Society, September 2004. & Allard, P., Short Account of the family of the late Rev William J Singleton., Manuscript 2000.

- Singleton, Henry, Some Recollections of the Singleton Family, Written for Margarita Wilhelmina Singleton by her Uncle. 1899.

- William J Singleton 1803; Thomas Lewis 1806; John 1808; Robert 1811; Anne Lewis 1813; Elizabeth 1816; Mary Matilda 1817; Henry Plant 1819.

- Singleton, J., Narrative of Incidents in the eventful Life of a Physician, 1891.

- Higgins, N., ‘The 1830s Tithe War’, Irish Roots, Number 2, 2003.

- 1871 Shipping Records, Assisted Passengers from the UK 1839.

- Margarita Wilhelma c1836, William Jones c1837, Theophilus Alexander c1838, Robert 1841, Henry Francis c1842, John 1843, Marshal c1844, Charles Steward c1845, Thomas Lewis 1847, George Lewis 1847. The last child in the family was Frances Georgina born at Kilmore 1851.

- Lowden, J., Kilmore Anglican Parish 1849-1999, Kilmore Historical Society Newsletter, March 2000.

- Daley, Charles, ‘Memoirs of a Pioneer Clergyman (The Rev F Hales) in Gippsland.’ The Victorian Historical Magazine June 1944 p72.

- Lowden, J., Kilmore Anglican Parish 1849-1999, Kilmore Historical Society Newsletter, March 2000.

- Lowden, J., Ibid.

- Lowden, J., Ibid.

- Kilmore Advertiser, 29 November 1884 “Reminiscences of Kilmore”

- Church of England Messenger, 5 August 1875.

- Singleton, M. W. A Short Account of the Family of the Late Frances Singleton, Wife of the Rev William J Singleton, M.A., written at the request of her son, the Late Theophilus Alexander Singleton, by His Sister, Margarita W Singleton, 1903.

- Allard, P, Short Account of the family of the late Rev William J Singleton

- Victorian Historical Magazine, Volume 37, p50, Allard, P., Short Account of the family of the late Rev William J Singleton.

- Mrs Lachlan Smith’s father was Charles Singleton, son of William Singleton and her mother was the daughter of Samuel Taylor.

- Taylor, N., The First Hundred Years: A Brief History of the Parish of St John’s Church of England, Bentleigh, Victoria 1854-1954, 1954.

- In 1859 the Cheltenham congregation presented to the Rev J H Gregory a communion set in appreciation of his assistance.

- Taylor, N., The First Hundred Years: A Brief History of the Parish of St John’s Church of England, Bentleigh, Victoria 1854-1954, 1954.

- Duggan, C., Excerpts from a History: A Parish & Its People, 2008.

- Minutes of St Stephen’s Church Committee, East Brighton, 17 September 1866.

- Minutes of St Stephen’s Church Committee.

- Minutes of St Matthew’s Church Committee, Cheltenham.

- Minutes of St Matthew’s Church Committee, 3 June 1868.

- Minutes of St Matthew’s Church Committee, 8 March 1871.

- Minutes of St Matthew’s Church Committee 4 March 1875.

- See Whitehead, G. Minister Dies from Starvation? Article No 462, Kingston Historical Website.

- Minutes of St Stephen’s Church Committee, 20 January 1868.

- Education Department , Correspondence.

- Education Department, Ibid.

- Certificate Registry Births Death and Marriages, Victoria.

- Inglis J., Kilmore Connections, Kilmore Historical Society, September 2004.

- Mentone & Moorabbin Chronicle, 17 May, 1890.

- Death Certificate, Registry Births Deaths and Marriages, Victoria.