Sir George Jones: Aviator and Military Leader

Queen Elizabeth 11 admitted George Jones to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire as a Knight Commander on 4 March 1954 at Government House, Melbourne, in recognition of his contribution as Chief of the Air Staff during the War with Japan. This no doubt was a high point in a career that commenced after leaving school with a Merit Certificate, working in a motor repair shop, joining the army as a private and subsequently progressing through the ranks of the Australian Air Force to become its leader. At ninety two years of age Jones wrote a brief autobiography from which most of the following information is drawn. [1]

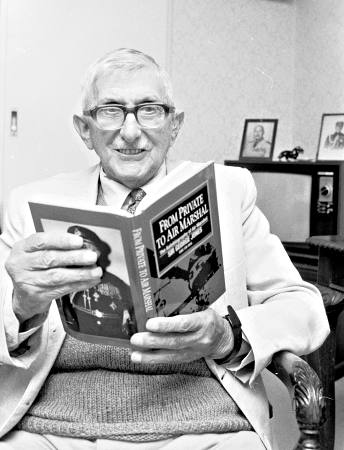

Sir George Jones with his autobiography, From Private to Air Marshall, 1988. Courtesy Leader Collection.

George Jones was born at Rushworth, Victoria, in 1896, the youngest of eight children. His father was a spare time gold miner who was killed after falling down a mine shaft, leaving the mother to raise eight children, ranging in age from twenty years to three months old George, on a unproductive farm. After a bad drought in 1902 the farm was sold and the family moved in to the town of Rushworth. It was from here that George left school at fourteen years of age first working for a local carpenter but later joining a brother in Fitzroy working in a motor repair business. Other positions followed. For a time he was assembling motor bicycles for A G Healing’s for a wage of thirty-five shillings a week and then repairing motors for Bevan Brothers in Malvern

In 1913 as part of the Compulsory Military Training Scheme he was a senior cadet at North Fitzroy but on reaching the age of 17 ½ he became a fully fledged soldier in the 29th Light Horse. On the declaration of war he found himself posted to a camp in Portsea guarding the Port Phillip Bay heads from any daring attack the Germans cared to launch, but George soon volunteered for service overseas. After a few weeks training and at only eighteen years of age he embarked on the troopship Kyarra in July 1915 for Gallipoli, via Egypt.

From Alexandria in Egypt they went to Lemmos Island where they boarded ‘a dirty little tub’, Sicilian Prince , for a two hour voyage to Gallipoli. Describing the situation at Gallipoli Jones wrote that rations were poor and water was scarce. ‘We had only two pints per day each, for all purposes, so nobody used it for washing. The result was that we all became infested with lice. … Flies were very bad, too, and this led to much dysentery and hepatitis.’ On Gallipoli’s battlefields he witnessed the death of a friend by enemy fire. He was glad to leave.

Bored with life back in Egypt Jones volunteered to join the camel corps. After a short time with the corps learning to ride and manage camels an opportunity came for him to join the first squadron of the Flying Corps as a mechanic. This chance opportunity he quickly took up, leaving with the squadron in October 1916 for training in Lincolnshire in England. On his twenty first birthday he graduated as a pilot and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant. On 16 January 1918 he was assigned to active service in France, having acquired sixty one hours and fifty five minutes of flying time. Jones recalled the day six enemy planes were shot down, two of which were credited to him resulting, no doubt, in the death of the German pilots but the feat gained him the Distinguished Flying Cross. By the end of the war Captain Jones had flown 113 operational sorties, downed seven enemy aircraft and flown a total of 279 hours 45 minutes.

On returning to Australia he first worked for wages as a mechanic but soon took a civil flying job delivering newspapers to towns along the Murray River. This only lasted a short time before he learned that the airforce was again recruiting. He applied and in August 1921 was given a short service commission as a Flying Officer. Promotion to Flight Lieutenant and a permanent commission followed success as the officer in charge of the aircraft and engine repair shop at Point Cook . He then sat the entrance exam to attend the Royal Air Force Staff College in England. Being successful he left for England with his wife Muriel and young son on the Ormonde in December 1928 with the new rank of Squadron Leader. The course he found difficult due to his lack of schooling in English Expression but with the support of his wife he graduated with a satisfactory report. Then followed a flying instructors’ course in Yorkshire from which he graduated top of the class with the highest rating obtainable.

Returning to Australia he undertook a number of senior appointments including command of flying training at Point Cook, Director of Training at RAAF Headquarters, and Director of Personnel Services. By January 1936 he had been promoted to Wing Commander. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Jones was the Assistant Chief of Air Staff responsible for preparing an expeditionary force of six squadrons to fight in Europe or the Middle East. However, before the plan could be activated the British government proposed an enormous training scheme to be located in Canada. The Australian government agreed to the advanced training of some of their pilots in Canada but retained the option of training the majority in Australia.

Jones was in Canada when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. He immediately returned to Australia by boat, arriving in Melbourne on 2 February 1942. Three months later at forty five years of age he was appointed Chief of the Air Staff with the rank of Vice Air Marshal. This came as a surprise both to him and others. He acknowledged there were nine other officers senior to him in the service and thought that William Bostock would have been the preferred candidate. Clearly Bostock, who had had rapid advancement in the service and was senior to Jones, saw himself as the better appointee and was bitterly disappointed when passed over. This decision of the Prime Minister and cabinet led to a stormy relationship between the two most senior officers in the RAAF that continued for the duration of the war.

After the Japanese victories in the Pacific and the bombing of Darwin the Allies formed South-West Pacific Area Command under General Douglas MacArthur. The Australian combat forces in the region were then transferred to that command on 17 April 1942. Prime Minister John Curtin agreed that the commander, of the Allied Air Forces would have operational control of RAAF units while administration would remain with the chief of the Air Staff and the Air Board. This meant the command of the RAAF was divided. William Bostock became the chief of staff to the American Allied Air Forces commander, with the rank of Vice Air Marshall, while George Jones with the same rank was chief of air staff. This divisive split in command led to many disputes over the provision of staff for RAAF Command Headquarters, over airfield construction, training, fighter section organisation, supply and other matters [1] Sproles and Yates write that by December 1942 it had become evident that the dual system was not working and it was agreed that an Air Officer Commander-in-Chief for the RAAF was needed in order to achieve unity of command in operational administrative matters. Such a position was never created so the clashes continued.[3]

When in 1944 the action front of the war was moving further north, away from Australia, Jones proposed to General MacArthur that the Australian forces should be reorganised into an expeditionary force under the command of Bostock. MacArthur seemed to accept the idea and asked that the details of the organisational plan be written down and sent to him. Jones did this but was surprised the next morning to receive a curt note from MacArthur complaining that the written details did not conform to what had been discussed. Consequently the proposal was not pursued. Jones believed that this incident showed that MacArthur was not above distorting facts to suit his purpose.

With the defeat of the Japanese General Blamey led the Australian contingent to the formal signing of the surrender on the American battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. Both Jones and Bostock represented the Australian Air Force. With the peace, air force squadrons were involved for a time in flying in supplies of food, clothing and medicines and repatriating prisoners from camps in South East Asia. Various units were also used to assist military units return to Australia from islands in the Pacific. But demobilisation of members of the RAAF was also a huge problem and a priority. Jones wrote that ‘in one year alone the RAAF was reduced from approximately one hundred and thirty thousand men and seventeen thousand women to a total of about seven thousand.’ Jones, facing a lot of scepticism and opposition became deeply involved in organizing a post war RAAF and divesting the organisation of a large amount of redundant equipment.

Subsequently to achieving peace with Japan, Jones was involved in the organisation of the Australian RAAF component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces and carried out several inspection tours of Japan. While he was Chief of the Air Staff of the RAAF squadrons served in the Berlin Airlift, the Korean War, and the Communist insurgency in Malaya. On 23 February 1952 at fifty five years of age he was discharged from the air force with the rank of Air Marshal. Jones took up the position of Director of Co-ordination with the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation at Fishermens Bend where he liaised between the company, the RAAF and the Department of Aircraft Production in the production of the Sabre jet fighter. He retired at sixty years of age in 1957 when his position at CAC became redundant.

Sir George Jones summed up his career:‘I am proud of the fact that, despite my relatively low standard of education, I was able to compete favourably with people who had college and university educations (proving that it is not necessarily the person with paper credentials who is the best for the job – a matter which should receive more consideration today). I also held the Chief of Air Staff position for a longer continuous period than any other incumbent, was the only one who had reached the post from the lowest rank in the services, and was the only Australian to hold the post during the war with Japan.’ At the end of the war there were 154,511 RAAF members, with 137,208 of them in the South-West Pacific. Overall 8632 personnel were lost in combat, with 2260 wounded and 1876 taken prisoner.

Seven years after being knighted he unsuccessfully stood as an Australian Labor Party candidate for the seat of Henty. This action caused a stir amongst some members of the community. Political analyst Malcolm Mackerras explained it was an ‘unusual situation’ for a knight of the realm standing for the Australian Labor Party rather than the Liberal Party. [4]

Following retirement Sir George Jones lived at Beaumaris and after some years took up residence at Pinehurst Aged Care Facility in Jellicoe Street Cheltenham. He died on 24 August 1992 in a Mentone nursing home where he had been living since January. Legally blind, he died of pneumonia. He was buried with full military honours at the New Cheltenham Cemetery. He was ninety-six years of age at the time of his death. [5]