Fairlie Taylor: School Library Pioneer and Cheltenham Personality

Fairlie Taylor. Kingston Collection Courtesy, Betty Kuc.

Fairlie Taylor’s real name was Addie Fairlam. She was born in Cheltenham in 1887 and lived there until she was nineteen. A very independent person, she was among a tiny group of women then who challenged the conformity of the times in which she lived. Fairlie was an early pioneer of women’s independence, a creative thinker of remarkable energy.

Addie Fairlam’s maternal grandparents came to Cheltenham in the 1850s from England, having been married at Chester. William Ruse and his bride, Elizabeth, called the area where they settled ‘Chesterville’ which became part of Cheltenham later, with Chesterville Road remaining as a legacy of the Ruse family. The Ruses’ daughter, also Elizabeth, married William Fairlam, the son of other English immigrants, and the couple settled in Cheltenham, moving eventually to a large house in Weatherall Road.

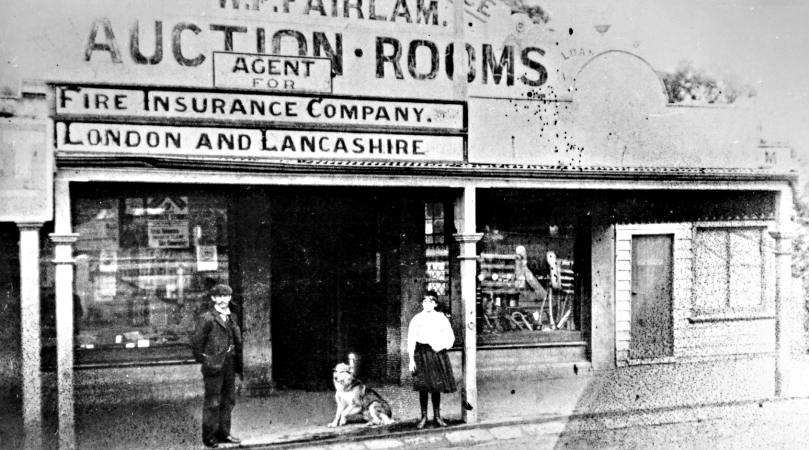

William Fairlam established an estate agency and auctioneering business in Charman Road right next to the railway crossing. He ran the business until the eve of World War 2 and the shop bore his name high above the front door until removed for renovations in 2009. Young Addie had a role in that shop for several years.

William Fairlam outside his shop and auction rooms in Charman Road, Cheltenham with daughter Addie (Fairlie Taylor) Kingston Collection, Courtesy Alan Treloar.

The Fairlams had three children; Percy, Addie and Eugenie. As a small child Addie had a happy time growing up in Cheltenham, mainly in the Weatherall Road house where the Fairlams lived for some years until the 1890s depression forced her father to sell out and buy a more modest home in Stanley Street near the station and his business. Addie attended the Cheltenham Primary School in Charman Road and loved learning. She read any books that were available and did well at her studies, but her adventurous spirit also pushed her into many games with other children in the small town with its rural surroundings. In her book Bid Time Return, written when she was over eighty, Fairlie describes in detail the way children played and enjoyed their free time over a hundred years ago. She quotes word for word all the rhymes they sang, she describes the birthday party games and the challenges. She once won a sixpenny bet by going through the nearby cemetery tombstones to the back fence of the old graveyard where she picked a piece of red gum foliage to prove she had beaten the fear of a ghost that other kids said was among the headstones. When Addie was just eleven she passed her tests to reach ‘the standard’ in fifth grade that qualified her to do the Merit Certificate course. This did not happen. Her father took her out of school and employed her in his shop, which was a newsagency and general store as well as an estate agency. It was then 1898 and the Fairlam business was suffering the effects of the depression of that time, so Addie was pressed into service.

The Fairlam family home in Weatherall Road, Cheltenham. Kingston Collection, Courtesy Betty Kuc.

Addie was devastated at this change in her life because of her love of school and the pursuit of knowledge. However, she had no choice. For the next five years Addie looked after the shop daily for the long hours of trading. She did have a trip to Tasmania for a holiday with relatives after contracting typhoid fever that necessitated a period of rest and recuperation. But her early teenage years were spent organising the retail part of her father’s business. She became known in the main street of the town and learned many of the foibles of other shopkeepers as well becoming well known to a lot of the Cheltenham citizens.

Addie was sent out to collect rents from Fairlam’s leased properties, she collected newspapers at the station, she was sent to the city to have documents signed, she cleaned up the rooms after auction sales and was generally her father’s trusted servant. William Fairlam was not an easy taskmaster and Addie earned her small wage with constant hard work. However, she used her spare time at weekends to enjoy herself. For a time she travelled in the horse tram down Charman Road into Balcombe Road and around Tramway Parade to an old home where she learned dancing from Miss Hyams. She described the joy of riding on the top deck of the slow tram and buying periwinkles at Beaumaris from an old Chinese woman. Addie stole a kiss from Dave White while working on rate notices with the future Mordialloc Mayor who was then a valuer’s clerk assisting Fairlam. She described him as a gentleman who respected her innocence. In her memoirs Addie recalls the excitement when the Bushmen’s Regiment paraded through Cheltenham in 1900 on the way to embarkation at Port Melbourne en route to the Boer War. There was also the drama of Queen Victoria’s death and the shops draped in black as people mourned the passing of the sovereign who had reigned since 1837, just two years after Victoria, the colony, had been settled by Batman and Fawkner. However, even though Addie made the most of her life as a shop servant she longed for a return to education.

Members of the Third Bushmen’s Contingent at Cheltenham. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

At the end of 1903, when Addie was nearly sixteen, her friend May Thurling of Mentone, visited her one day and told her about the joys of being a student at the Simpsons’ School, the forerunner of Mentone Girls’ Grammar School. Addie took things into her own hands and visited the Simpsons. Four sisters ran the school with Effie as the main spirit behind the enterprise. Effie Simpson agreed to take Addie as a pupil on trial provided she took coaching from the Simpsons’ mother in order to get her up to the standard of sixteen-year-old students at the school. Then came the crucial confrontation with her father. Addie’s mother agreed to help her but William Fairlam was very annoyed to be losing his shop worker. He said nothing, neither agreeing nor disagreeing with Addie’s decision to enrol at school, but when the school account for more than a guinea was left on the kitchen table he left the money overnight without saying a word. So in 1904 Addie was back at school.

In her three years at Mentone High School, the official name of the small college, Addie made good progress. She was top of the class in several subjects and took part in all the school activities including the Jollity Club which put on plays and entertainments. Annette Kellerman was a classmate of Addie’s. Later a famous swimmer who nearly became the first female to swim the English Channel, Annette was already in show business, starring in a city production at Wirths’ Olympia that featured her swimming in a glass tank. When the Brigidine nuns opened a convent college in the old Mentone Coffee Palace Annette left the Simpsons’ school and studied with the nuns for a short time. Full of devilment, Addie and a friend knocked on the convent front door one day and told the nun that they wanted to look over the school in the hope of becoming boarders. They gave false names and country addresses but the nun woke up to their tricks when they tried to imitate the nun’s reverent actions when passing a religious statue. They were taken over the college property and met Annette, a result they had hoped for in the first place. Soon after this Annette Kellerman left school and travelled to London and Europe where her international show business career began.

By the time she finished at Simpsons’ Addie was eighteen and had fallen in love with Callum, a handsome local boy who was about to enter Ormond College to train as a minister of religion. The couple met often at the back of the Cheltenham cemetery under the red gum tree that Addie had reached when she won her sixpenny bet. Addie and Callum remained friends but their respective careers separated them for years and World War 1 took Callum away for a long time during which Addie became involved with another man whom she married.

Addie and her husband on the occasion of their wedding. Kingston Collection, Courtesy Betty Kuc.

After leaving school in 1906 Addie spent the next year tutoring local students. William Fairlam wanted her to return to his shop but she refused, wishing to do something with the education she had received. Luckily for Addie she became aware of the Teachers’ Training College in Grattan Street, Carlton, where Frank Tate, Education Director, had begun crash courses to solve the teacher shortage. She gained a place in this program. Addie trained as a rural teacher, equipped to handle the small one-teacher school experience, and she lost her first name forever. Somebody in her course group nicknamed her ‘Fairlie’, a corruption of her surname, and it stuck, even after marriage when she became Fairlie Taylor.

As Miss Fairlam she was sent to a succession of small country schools over the next decade, often being required to set the school up from scratch. She had to travel, sometimes on horseback, to outlying small settlements and find board with local farmers usually finding the resources were very poor, throwing all the pressure on to her own abilities. She told stories, sang, put on concerts and did the ordinary school tasks in places that ranged from Gippsland to the Western District. Then she would be posted to the city again and out to Diggers Rest. Fairlie Taylor gained a wealth of experience by the time the war ended and she was about to be married.

Fairlie and Ben were married in 1920 and for a time the couple enjoyed a happy life. Bronwyn, Fairlie’s only child, was born in 1921. Ben and Fairlie settled in the district near Emerald on a mixed farm that never provided them with a satisfactory livelihood. Despite backbreaking work they were desperately short of money and eventually the farm was sold to allow a move to a less expensive holding. It too was unprofitable. The marriage became strained as Ben failed to realise his ambition of providing for the family. Fairlie began writing stories and had many published in women’s magazines. She offered to return to teaching but this seemed to displease her husband so the 1920s elapsed with the relationship deteriorating. Fairlie’s health became a problem and she had surgery in 1928 with complications keeping her in St Vincent’s hospital for six weeks. It appears she and Ben separated after this and she lived in Melbourne with Bronnie, her daughter, from then on. Fairlie is rather reticent about her marriage and the circumstances of its breakdown but she mentions that Ben did send money for Bronnie’s needs and visited her occasionally. Interestingly, she mentions that on the eve of her wedding she fleetingly saw Callum, her old Cheltenham flame, in a crowd on Flinders Street station. From her description of that sighting and her feelings during the brief incident one can gather that he was her true love.

Fairlie and Ben leaving the church after their wedding, 1920. Kingston Collection, Courtesy Betty Kuc.

Between 1928 and 1933 Fairlie survived and paid the rent by having stories and articles published in the Women’s Mirror, the New Idea, and, among other publications, The Herald, then a Melbourne daily paper. Life was tough but eventually she made contact with people at PLC (Presbyterian Ladies’ College), the school she wanted Bronnie to attend. Luckily the principal of PLC had met Fairlie when she was a teacher in rural schools and had been impressed with her work. He offered her a job. Knowing about her writing and her love of literature, he wanted her to take over the school library and to involve it in the day-to-day work in the classrooms. It was Fairlie’s big break, just the position that suited her interests and skills.

At PLC Fairlie Taylor allowed her love of books full rein and began an imaginative program of displays, talks, radio programs and other innovative moves to put the library into the forefront of education. In 1936 she introduced filmstrips as a way of dealing with certain topics in the library setting. Her name became known in Melbourne educational circles and people from universities, training colleges and schools visited her library. She spoke at conferences, did radio broadcasts on the ABC and was consulted by a wide variety of people interested in this field of education. After a break in the early forties she left PLC and went to MLC (Methodist Ladies’ College) to continue her library work until retirement in 1953.

Fairlie spent an active retirement involving herself in a wide variety of part-time pursuits, mostly in the field of education. In 1976 she was awarded the British Empire Medal for services to education. By then she was living in Armidale NSW to be close to her daughter who had moved there for her career in tertiary education. In her late eighties Fairlie continued to correspond with old friends and interest herself in the issues of the day. She became ill when she reached her early nineties and died at Armidale on 18 July 1983.