John Herbert Gregory: Pioneer Anglican Priest [1]

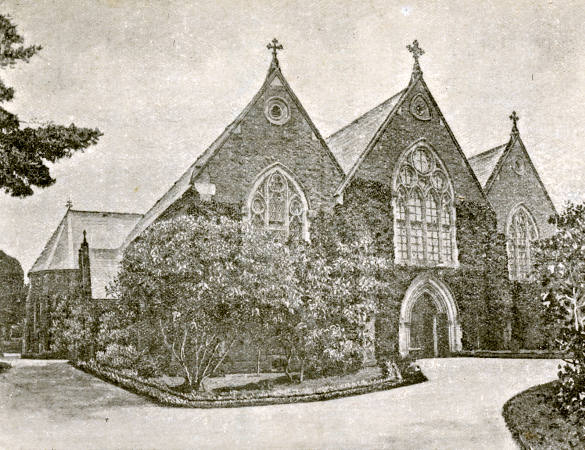

Christ Church Dingley. The foundation stone was laid by John Herbert Gregory on 12 February, 1873. Courtesy Helen Stanley, Kingston Collection.

The early European settlers, on arrival in the civil parishes of Moorabbin and Mordialloc, first claimed land and set about clearing the scrub so they could construct shelters for themselves and families. To ensure their survival, they hunted, created pasture, grazed cattle and grew fruit trees and vegetables. The need to provide for the education of their children and for the spiritual welfare of themselves and other members of the family quickly followed. Most of these settlers brought their religious practices and beliefs from Britain and Ireland, and sought to re-establish them in their new environment. Several of the early pioneers held prayer meetings in their homes and invited visiting preachers who often travelled great distances over poor roads, better described as tracks, and through dense scrub to lead these services.

Thomas Attenborough and his sister Mary arrived in Melbourne in July 1853 and purchased over a hundred acres of bushland in the Parish of Mordialloc, where they built a house which they named Dingley Grange. It was there that Thomas and Mary, loyal members of the Church of England, invited friends for prayers on Sunday. For these prayer meetings Thomas engaged clergymen from Melbourne to conduct the service and preach. One of the individuals involved in these meetings was the Rev John Herbert Gregory, a man who became a firm friend of both Thomas and Mary. Later Mary donated land opposite Dingley Grange and paid for the building of Christ Church. It was the Rev John Gregory who laid the foundation stone of the picturesque English style church and he was present seven months later in September 1873, when the completed church was dedicated by the Bishop of Melbourne, the Right Reverend Charles Perry. That same afternoon two baptisms were conducted by Gregory in the presence of a congregation of 180. Less than three years later John Gregory was back at the church conducting the funeral service of Mary. She had died from diabetes on 22 June 1876. The service at Dingley was conducted by Rev Henry Plow Kane and Rev John Gregory and attended by a congregation of 250 people. [2] John Gregory continued his association with Christ Church Dingley and Thomas Attenborough because he was named a trustee in Mary’s will. She left a considerable amount of property, the income of which was given to the Dingley church and to the Melbourne Diocese of the Church of England. [3]

Foundation Stone of Christ Church Dingley. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

John Gregory was born in London on 11 January 1827 and it was there that he went to school. He attended Mr Atkin’s private school in St John’s Wood and then Blackheath Proprietary School, his intention being to attend Cambridge University. His father, George Phillip Foster Gregory, a solicitor, upset this plan by taking the position of Prothonotary and Registrar of the Supreme Court of New South Wales on 14th August, 1843, at a salary of £800 per annum. [4] The family sailed from England as unassisted passengers on the barque Florentia, arriving in Sydney on 14 August 1843, [5] when his salary was reduced to £650 [6]* Sue Allaby - Correspondence]

For almost two years Gregory was an articled clerk in a lawyer’s office but he decided to seek ordination as a minister in the Church of England. To further this plan, together with his brother, he began his studies for the ministry at St James College at Lyndhurst in Glebe. (His brother, the Rev George Edward Gregory, incumbent at Canberra drowned in the Molongolo River a tributary of the Murrumbidgee on 20 August 1851while returning from country duty) This college was the fore-runner of Moore Theological College and was the first training college for Anglican clergy in Australia. At that time the small college was known for the ‘catholic’ stance of some of the lecturers. It was a time when many Church of England members were concerned about the influence of Anglican clergy within their ranks who had joined the Oxford Movement, a group who wanted to restore earlier ‘catholic’ or high church liturgies. John Henry Newman, a leader in the movement, had been received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1845 and two prominent clergymen in Sydney, Thomas Makinson and Robert Sconce also turned to Rome. Sconce, whose teaching it was said ‘smacked of Rome’, was a lecturer at St James College and may well have influenced Gregory’s attitudes and practices. [7]

Gregory offered himself to Bishop Perry of Melbourne as a missionary to the Aboriginals but was offered the position of travelling bush missionary. He was ordained by the bishop on Trinity Sunday 1850 as a deacon and the following year as a priest.[8] During 1850 he travelled extensively throughout Victoria, visiting Western Port District, Campaspe and Loddon Districts, Bacchus Marsh, and the Mount Alexander goldfields. It was on 19 July 1850 that he set out for Cape Schanck in the Western Port District by way of Dandenong where he conducted a service attended by twenty five European settlers and approximately twenty five Aborigines who belonged to the Native Police Corps. He also visited the latter group in their barracks where he explained to them ‘the great truths of the Gospel’ which they ‘all appeared to understand’. [9] On his return from Cape Schanck he visited the lime-burners at Point Nepean and called upon several of the stations of squatters near the shore of Port Phillip Bay. During this time he administered the sacrament of baptism to twenty nine children and held week day and Sunday services which were ‘gladly and well attended.’ [10]

At the end of 1851 he went to Bendigo, later serving there as the first Anglican priest on the goldfields. There services were conducted in primitive conditions with the minister often addressing his congregation in the open air and preaching from a pulpit which was the stump of a gum tree. [11] The story is told that two men from a group of miners decided to beat him up and chase him from the district. In response to this aggression he fought both of them, earning their respect and gaining them as members of his goldfield congregation. [12] Four years later, on 4 May 1855, he accepted the appointment as Incumbent of the Parish of Prahran from which was created the Parish of All Saints, East St Kilda. [13] It was at All Saints that Gregory remained as vicar for 38 years until his retirement on 17 September 1893. While at All Saints he conducted services beyond his parish, at Malvern, Dandenong and a monthly service ‘in and near Cheltenham’ where forty four grateful members of the district presented him with an exquisite silver set of communion vessels in 1859. [14] But a major focus of his attention was the building of the East St Kilda church.

Communion Set given to the Rev John Gregory by residents ‘in and near Cheltenham.’ Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Towards the end of 1857 John Gregory promoted the idea of building a church on the site reserved for that purpose in Chapel Street. A meeting was called to appoint trustees of the land and subsequently designs for the building were sought. From only two proposals submitted, the work of Nathaniel Billing was accepted. The foundation stone was laid by Bishop Perry on 8 November 1858 but because of difficulty in raising money only three bays of the nave were built. [15] When the first service took place on 8 December 1861 the walls were not plastered, there was no ceiling and individual members of the congregation had to provide their own chairs. Extensions in 1868 provided a better but temporary chancel, the completion of which was attributed to the energy and perseverance of the vicar who personally obtained a considerable portion of the money required. [16] Bishop Perry called it a ‘fragment of a church’. [17] Further extensions were completed in 1875 when the temporary chancel and sanctuary were replaced and transepts added. The final improvements occurred in the 1880s at a prosperous time and the church was consecrated, debt free, on 8 November 1892 by the Bishop of Melbourne, Dr Goe, during a major economic slump. [18]

All Saints, Church of England, St Kilda.

Gregory’s theological position was described as that of a high churchman. He used vestments occasionally, a situation unusual at the time, and was one of the first to introduce hymns into services. Under him All Saints became known for its rich liturgical and musical life. Mr Firebrace recalled in 1908 that the chanting of psalms commenced in 1858 and the first choral communion was on Easter Day, 1865. [19] Earlier Bishop Perry while praising many aspects of Gregory’s work was at odds with him about the place of music in worship. ‘The mode of conducting Divine Service in his Church has not been altogether such as I approve,’ he said. [20] Gregory saw Perry’s comments regarding the use of music as an infringement on the liberty of churchmen, a liberty for which he was prepared to fight, and he wrote a long letter to the bishop justifying his position. He wrote ‘Intoning the Prayers in Parochial and other Churches and Chapels is not a modern innovation, but the revival of the ancient plain song of the Church of England.’ He made his position clear. [21]

According to George Vance, the Dean of Melbourne, who preached the eulogy at the memorial service on Gregory’s death, Gregory was a clergyman who in general focussed his attention on the affairs of the parish rather than concerning himself with diocesan issues. ‘Once or twice, indeed under a conviction that some Church law was about to be broken or some sacred principle to be surrendered, he flung himself with impetuous feeling into the controversy of the hour; but his point once gained or lost, he retired again to his parish and his study and the Church assembly or the newspaper columns knew him no more.’ Vance also said, ‘before all things Gregory was the pastor and parish priest…In the public assemblies of the Church he took little part, being somewhat too impulsive to lead, and too independent to follow.’ [22]

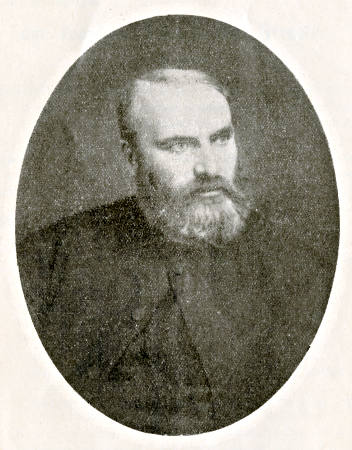

The Rev John Herbert Gregory, Vicar of All Saints, St Kilda, 1855-1893.

A newspaper reporter in 1869 described the incumbent; as ‘a man in the prime of life, a very manly figure with good features overshadowed with beard and riotous whiskers, clear greyish blue eyes, deep set, and rather frank, defiant, and more trustful than keen, curious and observant.’ He praised a sermon as a gem lasting only about thirteen minutes. ‘There is a frank and trustful manliness in Mr Gregory that no art can simulate, and no rhetoric can portray. His diction suits his Church – clear, simple, robust, and irresistible in the simplicity of pure taste and of lofty wisdom.’ [23]

People who reflected on John Gregory’s personality and style pointed to his spirit of reverence as well as his great fund of humour and ready wit. Bishop Corbett, who became the Roman Catholic Bishop of Sale and earlier the parish priest of St Mary’s Church in Dandenong Road, saw Gregory ‘as a man singularly free from religious fanaticism, a hater of narrow-minded bigotry and always the cultured gentleman.’ He recounted a story about John Gregory’s daily visit to the St Kilda Baths on Port Phillip Bay, both summer and winter. On one chilly morning when entering the particularly cold water he gave a shriek. When asked to explain his exclamation he replied, ‘Oh, you have evidently no ear for music; that was the Gregorian chant.’ [24]

During his time at All Saints John Gregory made several trips to Europe. One was in 1870 and another in 1880. On these occasions he took the opportunity to make contact with clerical colleagues, to observe liturgical developments in the home church, to purchase religious art for the enhancement of All Saints and to revive his physical and mental strength. Between these two trips he married. On 30 June 1877, John Gregory married Martha, the widow of Henry Rowe and daughter of Archdeacon Stretch. [25] They were married at Christ Church, South Yarra by Martha’s uncle, the Rev John Cliffe Theodore Stretch. [26]. Martha, the widow of Henry Rowe, was 28 years old while John Gregory was 50 years of age. Together they had two children Teresa Catherine and Herbert George.

After the consecration of All Saints in 1892, John Herbert Gregory retired and joined his family in England. Holden, in his history of All Saints, concluded that Gregory was a man with leadership qualities, a person with intellectual breadth and curiosity. ‘Despite minimal academic training he had a life long passion for collecting books. He left while still an effective working professional but feeling his age and health had become an issue,’ Holden said. [27] At the parish farewell held in the school room in October 1893 Gregory urged that ‘the church live as a united family, not divided but associated in a united spirit of peace. ‘Love, was wanted more in the Church and petty differences should be dismissed,’ he stressed. Advice such as this has relevance for the worldwide Anglican community today. (How Gregory would have reacted to women priests and bishops, and the issue of homosexuality can only be guessed – issues regarded as not petty by some.) After returning to England he resided in Hurst Green, Sussex and it was from there that he regularly assisted the neighbouring clergy and preached at the Etchingham church and less frequently at the Hurst Green church. He did this until his death on 2 April 1897 from diabetes. He was buried in the churchyard of Holy Trinity Church, Hurst Green, Sussex. [28].

Footnotes

- The assistance of Carmel Hogan and Sue Allaby in preparing this report is gratefully acknowledged.

- Kent, Phillip, Christ Church Dingley: 1873-1973.

- Public Records Office of Victoria, Probate of Mary Attenborough’s Will.

- This salary level contrasts with John Gregory’s annual stipend of £220 a few years later as the vicar of All Saints.

- McLaren, Ian, F., All Saints’ Church of England, East St Kilda, 1858-1958 Victorian Historical Magazine Vol 31, No 2, Nov 1960 p106-117.

- Allay, Sue, Correspondence, 2010.

- Bolt, P., Southern Cross, 27 February, 2006.

- McLaren, Ian, op cit. Gives date of ordination as a priest as 15 June 1851.

- Church of England Messenger, September page 251.

- Church of England Messenger, ibid.

- Church of England Messenger 1 May 1897 page 59.

- Holden C, Saints, Sinners and Goalposts: A History of All Saints East St Kilda, 2008 p32.

- McLaren, Ian., op cit.

- Returned to the parish of St Matthew’s in 1939, arranged by John Gregory’s daughter Teresa. Allay, Sue, correspondence.

- The Argus 9 November 1858.

- In Preparation for the Jubilee: All Saints’ Church, 1908 page 15.

- Church of England Messenger, 1 May 1897.

- Prahran Telegraph, 12 November 1892.

- All Saint’s Church, East St Kilda, Diocese of Melbourne: Its Past and Its Aims 1858-1908.

- Holden, C., op cit, p177.

- J F Newcastle in Its Past and Its Aims p27 & Gregory J H , Church Music , 1857.

- Church of England Messenger 1 May1897 page 59.

- Church of England Messenger, ibid.

- In Preparation for the Jubilee: All Saints’ Church, 1908 page 18.

- Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages.

- Martha’s cousin, the Rev John F Stretch conducted services at St Matthew’s Cheltenham while he was a curate at St Andrew’s Brighton. Later he was appointed Bishop of Newcastle.

- Holden C, op cit page 34.

- Allaby, Sue, Correspondence.