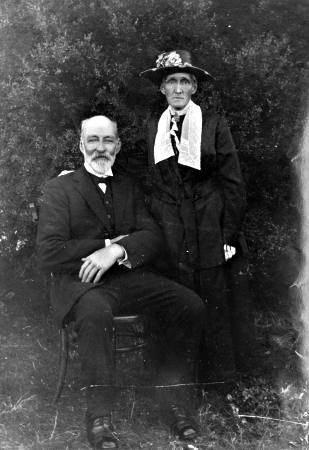

William and Annie Black

William and Annie Black at Chelsea. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

William Black died in his own bed in 1927 at his residence on the corner of Swanpool Avenue and Black Street, Chelsea. He was eighty five years of age. Married to Annie Maria Agnes Knight, he was the father of ten children, two of whom were born at Black Dog Creek near Chiltern while others were born at South Brighton. He was active in community and church affairs during the course of his life.

William was born at Swanpool near Benalla in 1842 to Thomas Black and Sarah Jane, nee Bull. At twenty five years of age he married Annie Knight at Beechworth, Victoria. At the time of the marriage at the Church of England at Beechworth both William and Annie were living at Chiltern. With the birth of their first daughter in January 1872 a more precise address was noted; ‘Black Dog Creek near Chiltern in the Indigo United Road District.’ [1] William’s occupation was listed as miner. Gold was discovered around Chiltern in 1858-1859 where the gold was primarily extracted by sinking shafts that were hundreds of feet deep, in contrast to the situation at Beechworth where the gold was alluvial, found in the sand and gravel in the beds of creeks. By the early 1900s gold production at Chiltern was dwindling. Whether William was successful in finding gold is unknown but on moving to South Brighton he was able to marshal sufficient money to either place a deposit on, or to purchase, land.

Annie, William’s wife, was born in London in 1849 and journeyed to Melbourne on the Lord Delaval with her family. By 1875 William and Annie were living in Bluff Road in what was then called South Brighton. Shire Council Rate Records show that William as a market gardener owned three portions of land in Bluff Road, two of five acres and one of ten acres. On two of these properties were four- roomed houses. In 1887 these properties were valued at £20, £17, and £35 but two years later, at a time when property sales were booming they had increased in value to £45, £37, and £75. [2]

While living a South Brighton eight children were born; Alfred Herbert Thomas (1875), Thomas Ernest Edwin (1877), Walter Henry Arthur (1879), Sydney Rupert Horace (1882), Bertha Rosa Annie (1885), Robert Harold Selwyn (1888), Donald Clarence Roy (1889) and Charles Augustus Neil (1891). During this time William Black played a part in the establishment and development of St David’s , Church of England at South Brighton (now Moorabbin). He was an early and active member of the church committee, moving motions about handbills for mission services, raising concerns about the emptying of the closet pan and railway porters lighting fires within a short distance of the church (at that time the church was on land in Point Nepean Road and where formerly the City of Moorabbin Council Offices were located). Later, his eldest son, Francis William Black, also served as a guardian and secretary of the church committee. [3]

By 1891 Annie and William were each listed as owners of five acres in Bluff Road but the ten acre property had been sold. Six years later he had purchased land in Chelsea which was part of the land originally selected by Mark Foy when the Carrum Swamp was opened up by the government to European selection in 1871. It was on this land that William Black proposed to settle his eldest son, Francis William, while he and the other members of the family resided and worked the land at Bluff Road. First, however, the land had to be cleared and buildings erected. Later William reversed his decision, deciding to leave the older boys at Moorabbin while he, Annie, and the younger children settled at Chelsea. Bertha Armstrong (Black) recalled that she, as a fourteen year old girl, her parents and the four younger surviving boys moved to Chelsea in July 1899. Charles Augustus Neil had died in 1892 aged six months. By 1899 fencing and stables had been erected and a house built by Caudwell’s of Mentone. Nevertheless, Bertha wrote ‘Conditions were primitive. Water for washing and general purposes was pumped from a well sunk about twelve feet, and drinking water was from a small rainwater tank.’ [4]

First meeting of Chelsea Historical Society. Mrs Bertha Armstrong (daughter of William and Annie Black), Mr J. H. McCarthy (first porter in charge of the railway station) and Mayor of Chelsea, Cr Hummerstone. 1964. Courtesy Leader Collection.

Potatoes and onions were the major crops that were taken to the Victoria Market in Melbourne by twenty year old Walter on a wagon drawn by horses. While there he purchased other fruit and vegetable supplies required by the family. Annie Black herself also purchased provisions at Mordialloc and sometimes as far away as St Kilda, travelling in her pony and dog cart. The fowls, in a large poultry run surrounded by fencing to keep the foxes out, provided eggs and the occasional bird for the table. There was also a cow that kept the family in milk, butter and cream for most of the year. To go to Melbourne members of the family could use the steam train service by walking to the Aspendale Racecourse Siding where a train could be hailed by taking a red flag from a box and waving it to the driver in the oncoming train, indicating their desire to join him and any other passengers. Later William was involved in gaining a station at the town called Chelsea, named some believe after the birth place of Annie’s mother. Like other land owners in the area William contributed £10 towards the cost of establishing a station.

Annie Black with child outside the dairy. William Black in the background. Courtesy Chelsea and District Historical Society.

After moving to Chelsea, William Black continued to involve himself in community concerns. Like other gardeners on the Carrum Swamp he was plagued at times by excess water caused by heavy rainfall aggravated by high tides and boisterous winds, and he welcomed various attempts to protect the settlers from flooding. In 1889 local people formed a trust called the Carrum Irrigation Trust. Its task was to improve the drainage through the construction and maintenance of channels. At first John Keys, Hugh Brown, Thomas Keys, Edward Nicholls, George Cornell and Alfred Bradshaw were elected as commissioners, but later William Black was elected to the Trust. [5] In 1903 Commissioner Black, along with fellow commissioners, was arguing the case with the government that some relief be provided to swamp settlers from the financial burdens they were being forced to carry. The Trust owed £1450 to the Water Supply Department yet only had £300 in hand. If the farmers were pressed to pay the owed balance many would be forced off the land. Black said he had purchased his place for a homestead but unless relief was given he would be compelled to go elsewhere. [6] He took part in several deputations to the Minister and Premier on this matter.

Besides the tasks of caring for her family, Annie Black was involved in the established of the Church of England in the district, just as her husband had been at South Brighton. At the time there was no Anglican Church building between Mordialloc and Frankston. Together with Mrs Gwyn, the station mistress at Carrum, Annie Black worked to correct the situation. Land was purchased with the help of John Porter of Birtchnell Bros & Porter, Land & Estate agents, and a small building, described as a shed, placed there. Unfortunately it was unsatisfactory for when it rained umbrellas had to be put up to protect members of the congregation from leaks in the roof. After further money was raised by a committee led by John Porter as chairman, with Mrs Gwyn as secretary, and Annie Black as treasurer, a small church, St Aidan’s, was built by William Ryall and opened and dedicated in May 1902. It was said that if there was a committee meeting during the week Mrs Black would set off to walk to Carrum carrying a hurricane lantern. [7] A few years later with the development of the Chelsea township Annie Black once again found herself involved and committed to the building of a church. [8] Land had been purchased in Argyle Avenue but this was sold in favour of two blocks of land in Thames Promenade. (Later a third block of land was obtained due to the generosity of Mrs Nicholson). The foundation stone of St Chad’s Church was laid on 20 June 1914 and dedicated by the Archbishop of Melbourne on the day World War One commenced, 4 August 1914. In addition to her work for the church Annie was president of the local branch of the Red Cross Society and the first president of the Women’s Auxiliary. [9]

Two of Annie’s sons served in the First World War. Sidney, who had previously served in the military during the Boer War in South Africa, joined once again on 18 August 1914 only a few days after war was declared. He served at Gallipoli and in France. A younger brother, Donald, joined on 12 July 1915 and was killed in France, 11 April 1917. At first he was reported missing in action and not until some months later was his death confirmed. During this time and later Annie was writing to the military authorities seeking information about her son and the circumstances surrounding his death. The letter of 16 August 1920 reveals her frustration and grief. On that morning she received his identification disc and notification of his burial in a British cemetery near Cambrai. This she said came as a surprise because he had been noted as missing for eight months and the Department notified her that no details were available. Yet she pointed out that a ‘pal’ who was beside her son when he was killed informed the Red Cross of the circumstances surrounding his death and had since visited her and given her the information. She wanted to know what other information was available about where was he found, and to whom she needed to apply for assistance in obtaining it. [10]

At the time of her death in June 1923 Annie Black was described as a patriot, and a devoted wife and companion to her husband. She was seventy four years of age. William Black lived for a few more years until 1927 when he was eighty five years of age. He died in his sleep at his home ‘Swanpool’ in Swanpool Avenue, Chelsea. Both were buried in the Cheltenham Pioneer Cemetery.

Head Stone on the Black grave at the Cheltenham Pioneer Cemetery, 2010.

Photographer Graham Whitehead. Courtesy Kingston Collection.