David Abbott: Solicitor, Councillor and Pioneer

David Abbott, 1912. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

David Abbott was an early resident in the Parish of Moorabbin after purchasing land in 1876 adjacent to Holloway’s Gipsy Village. [2] He became a contributor and influential figure in the development of the district through land speculation and membership of the Shire Council of Moorabbin. By occupation he was a solicitor. In the various roles he played he was not always free of criticism or controversy. Yet at times he was praised and supported for his action. He gained substantial majorities on the occasions he stood for election to the Moorabbin Shire Council where he was intimately involved in the debate as to whether Sandringham and its surrounding districts should be severed from the Shire of Moorabbin to form their own local government.

Born on 3 November 1844 at Witham, Essex, to David Abbott, a shoemaker, and Amelia Abbott (Gamble) he was the third son, having two older brothers; Charles who was nine years old and Thomas two years. [3] At the time of the English Census of 1861 seventeen year old David Abbott was boarding with Frances Hills in the town of Great Coggeshall. His occupation was given as lawyer’s clerk. This was not the first time he was employed in a legal office if Sutherland is correct. Sutherland writes in Victoria and Its Metropolis that Abbott was engaged in a lawyer’s office when he was twelve years old. [4]

Without any letters of introduction, and at nineteen years of age, David Abbott travelled to Melbourne arriving on the Wellesley in June 1863 as an unaccompanied passenger. On the ship’s manifest he was listed as a ‘trader’ an appellation given to many passengers on the ship irrespective of age or gender. [5] Travelling to Warrnambool a few years after arrival in Melbourne, Abbott began working in the legal office of George Barber. Completing matriculation in 1869 at Melbourne University he commenced in that same year as an articled clerk to William Cleverdon of Chancery Lane, Melbourne. He remained for a little more than three years. By 1874 he had finalised his articles with William Hughes thus completing the balance of the proscribed five years as an articled clerk. [6]

At the age of twenty nine on 9 April 1874 he was admitted to practice as attorney, solicitor and protor on the motion of George Higginbotham, a former Attorney-General, a member of the Legislative Assembly for Brighton and later Chief Justice; an influential mentor. Abbott had served five years as an articled clerk, passed university examinations in law and history as well as passing examinations set by the Board of Examiners of the Supreme Court of Victoria. There was some questioning of the fact that there was no gap of twelve months between each university examination completed by Abbott, but Justice Redmond Barry decided that the rules required an academic year rather than twelve month period to elapse between the two exams. [7] This decision removed any doubt about Abbott qualifying for admission to the legal profession.

By 1875 he was practising as a solicitor on his own account in Collins Street, Melbourne.[8] His residential address in 1869 was given as 3 Lansdowne Street, East Melbourne, while at the time of his admission to the bar his address was 41 Powlett Street, East Melbourne. He moved his legal practice from Collins Street to 64 Chancery Lane c1878 and it was in 1887 he took Thomas Eales into partnership. [9]

As a lawyer David Abbott defended many people in the courts but was also obliged to defend himself in some actions. One such case was Robinson v Abbott heard by Mr Justice Holroyd in the Victorian Supreme Court in 1893. Mrs Robinson and her daughter had attended David Abbott in his office to receive more than £1000 from the release of a mortgage. With this new liquidity Abbott recommended to Mrs Robinson that she re-invest a portion of this money in the Brighton Caulfield and Moorabbin Property Trust. This was a company in which Abbott was a director and therefore privy to details of the company’s affairs. The advice was taken and five hundred shares purchased. Later Mrs Robinson learned that the shares she had purchased from David Abbot were his own; a discovery that occurred fifteen months after their purchase. In June 1891 the company went into voluntary liquidation and the following year Mrs Robinson was informed she could demand repayment of the money paid for the shares. It was said Abbott predicted disastrous consequences for the company’s future at the time when he sold Mrs Robinson the shares yet he did not warn his client of his revised assessment of the company’s future. As a consequence the court found him ‘wanting in candour when he should have been absolutely candid.’ The court ordered Abbott to pay back the purchase price of the shares plus interest of 6% per annum, in addition to calls made upon them, and to indemnify against all future calls for money. However he was acquitted from the most serious change laid against him, namely that he concealed his ownership of the shares with fraudulent intent. [10] A reviewer of the case in the Victorian Law Review pointed out that in the euphoria of the 1888 land boom the recommendation was understandable but by the time the case came to court in 1893 the suggestion would have been a joke. ‘So easy is it to be wise after the event’ was the comment.[11&12]

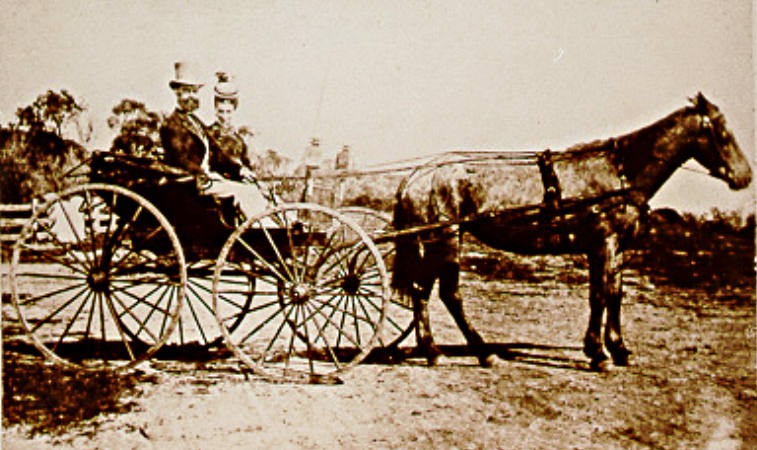

David Abbott, President of the Shire of Moorabbin accompanied by his wife Elizabeth, in carriage. Courtesy Sandringham and District Historical Society.

On 10 October 1876 on the occasion of his marriage to Emily Maude Elliott at St Peter’s Church of England in Melbourne he gave his address as Brighton. [13] This was Abbott’s second marriage as his first wife, Elizabeth Jane Woods, born in Tasmania, had died in May 1874, aged twenty. Emily Maude Elliott, Abbott’s second wife, was born in Collingwood, Victoria in 1853. Later the family moved to Beechworth where six siblings were born before the family moved back to Melbourne. [14] On Emily’s marriage certificate she gives her place of birth as Beechworth but on the birth certificates of her children her place of birth is given as Collingwood. Emily’s father was noted on her marriage certificate, as a member of the civil service. While David Abbott had no children with his first wife, Emily gave birth to three children: David (1877) Frank Walter (1880), and Elsie Maude (1884) all were born at what is today Sandringham . It was in 1876 that he commenced building his substantial house ‘Coggeshall’ at Picnic Point where he resided until the early 1900s.

Coggeshall, Sandringham, c1900. Courtesy Sandringham and District Historical Society

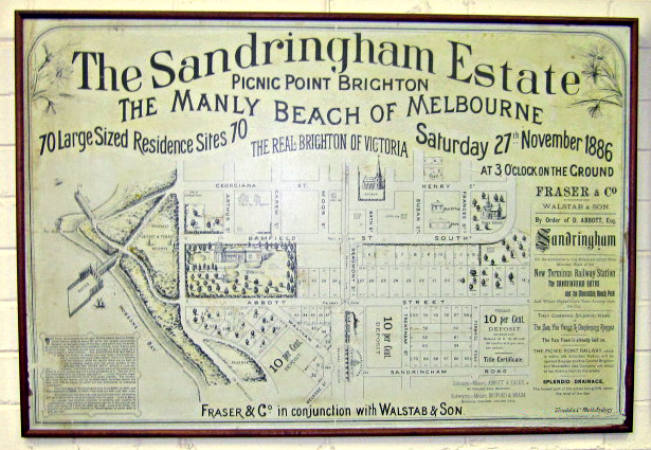

David Abbott’s first purchase of land at Picnic Point was four acres plus a few perches in 1876. It was on this land that he built his residence. Subsequently he added to this holding with a large purchase from Roger Leech in 1879 followed by further purchases of other land in 1883 and 1884, making him a substantial land owner in the district. [15] Some of this land he held in partnership with J H Hood and Henry Hodges, barristers and later judges in the Victorian court system. In all, his acquired land holdings exceeded 37 acres in total. [16] On 27 November 1886 David Abbott advertised in the Brighton Southern Cross the sale of seventy large residential sites with frontages varying from 220 feet to 60 feet. Only fifteen of these lots were sold. However, after the opening of the railway from Brighton Beach to Sandringham, which crossed some of his land, Abbott disposed of all but eight acres of land around his residence to the Sandringham Property Company in which he held shares. This company went into voluntary liquidation in August 1889. [17] The Moorabbin Shire Rate Records of 1892 again notes David Abbott as the owner of much of this land. In addition to this property Abbott was involved with Bent and Howden in the Brighton, Caulfield and Moorabbin Property and Investment Company which became defunct in 1888. [18] He also held two acres of land in the Parish of Casterton, County of Dundas. [19]

Sandringham Estate The Manly Beach of Melbourne, 1886. Courtesy Sandringham and District Historical Society.

By 1900, rate records of the Shire of Moorabbin show that David Abbott owned land in Littlewood, Mills, Willis, Hampton, Abbott, Trentham, Susan, Waltham and Bamfield streets, and Sandringham and Bay roads. Judges Hood and Hodges, with Abbott, owned thirteen lots in Abbott and Trentham streets and Sandringham Road. This land was sold from 1903 to 1909. [20] Margaret Glass notes that the sales netted Abbott somewhere in the order of £2000. [21] In October of 1909 he sold Coggeshall and its surrounding land to Elisha De Garis, a commission merchant who later became a councillor in Moorabbin Shire Council for a short time. [22]

In 1890 a piece published in the Brighton Southern Cross described in some detail the nature of Abbott’s residence; the rooms, the decorations and the unique and costly furniture imported from overseas:

The drawing room ceiling is tinted in salmon colour with celestial blue frieze very richly ornamented in Frenchy renaissance centre pieces and cornices picked out in yellow, buff, light pink and terra cotta. The enrichments of cornice and centre flowers are etched out in gold. …The entrance hall walls are tinted a yellow stone colour with a soft amber dado separated from the wall by a pink railing border … The arches and pilasters in plastic style are richly picked out in fruit and flower work. The walls of the dining room are finished in a buff; the dado in terra cotta, with a broad pink band and a rich stencil border on lines of various shades. … The ballroom ceiling is tinted in blue green richly ornamented … while the walls are tinted in orange colour with a five foot dado in pink. … The study, bedrooms and nurseries are finished off in much the same artistic style; all the colours harmonizing nicely. There is a total absence of the garish colouring, so frequently noticed in modern decorations. The ceilings and walls throughout are treated in the various tones of kalsomine, the dados in flatted paint as well as all centre flowers and the principal cornices. The body colours were selected by Mrs Abbott and we are informed by the artists who carried out the work that excellent taste was displayed in the selection. [23]

Entrance Hall of Coggeshall. Courtesy Sandringham and District Historical Society.

Some of the purchases for the Picnic Point home were made on a trip David Abbott made with his wife and family to Europe. Purchases of rare pictures were made at Whiteley’s establishment in London and other galleries found there. This overseas visit was one of several made by the Abbotts. In March 1882 the Abbott family travelled to Europe on the Chimboraza and in 1888 he was granted six months leave of absence from his position as councillor in the Shire of Moorabbin to travel, accompanied by his family, to America.[24] This may have been the time when he visited India, China, Japan and the Sandwich Islands. [25] In May 1890 the Brighton Southern Cross, in a short paragraph, welcomed back David Abbot and family from their twelve month trip on the continent and were pleased to note that they had ‘much benefited by their sojourn’. One final trip was made to England before his death in 1921.

One excursion came after Abbott had resigned from his membership of the Moorabbin Shire Council in August 1887. This followed a torrid time in Council where the questions of severance for the Sandringham district from the shire and the construction of a tramway from Picnic Point to Cheltenham and Mordialloc were vigorously debated. A key opponent to Abbott in these debates was a fellow councillor from the West Riding, Harold Sparks. [26]

David Abbott first stood in council elections in 4 August 1884. Prior to joining the council Abbott was writing to The Argus complaining about the removal of rocks from Half Moon Bay by the council to be used in road construction. [27] He took this cause up when he first entered council with the support of a substantial majority of West Riding voters, but it was the issue of severance of the Sandringham district from the Shire of Moorabbin that became a major focus.

Abbott was joined by Harold Sparks on council as a representative of rate payers of the West Riding in September 1885. Sparks was employed by Charles Henry James, a major land owner, as a general manager and confidential clerk, and once in council he became a vocal and vigorous supporter for the severance of the West Riding from the Shire of Moorabbin to form a new shire. In addition, he was concerned with the establishment and promotion of the Beaumaris Tramway Company. Both these issues were of vital concern to his employer, Charles Henry James, as their achievement would have enhanced his prospects of selling his large land holdings at Black Rock and Beaumaris, making large financial profits. The clash between these two council representatives was toxic with the Brighton Southern Cross supporting Sparks while the Cheltenham Leader sided with Abbott. [28 & 29] Several petitions and counter petitions were circulated either advocating severance or condemning it with the support of either councillor.

While mentioning the possibility of severance from the Shire of Moorabbin, David Abbott, when first accepting nomination to stand in the council elections, made it clear that his personal preference was for sub-division; the creation of a new riding. He argued a new riding would increase their council representation, provide greater control over the direction of council expenditure and a chance to decrease the domination of market gardener interests. [30]. At a meeting held in January 1885 Abbott again indicated severance was not his favoured option but said if the majority of his constituents in the West Riding indicated they wanted severance from the Moorabbin Shire he would not oppose them. [31] In August 1886 the issue was raised again when the newly formed Mutual Improvement Society proposed a debate on the issue to be held in the Cheltenham Mechanics’ Hall. Sparks was to argue the affirmative case and Abbott the negative. Abbott declined to take part, offering instead to present a new recitation about a shipwreck as a substitute. He said it was inappropriate for him as President of the Shire to debate an issue that had been discussed by council and resolved that the West Riding should be divided giving the district additional representation in council. Later his support for the sub-division option and opposition to severance became much stronger. [32]

Abbott’s hardening stance against severance was seen by some to relate to his desire to have the Brighton railway line extended from Brighton Beach to Picnic Point where he had land for sale, and to a deal with Thomas Bent. [33] It was known that land sales benefited from the presence of a transport system, particularly a government railway. Land developers in their advertisements usually drew attention to the presence of a railway line, or to a line to be constructed in the future, as did Holloway with the ‘Town of Beaumaris near Brighton.’ [34] Gibb quotes from an editorial in the Melbourne Times, 27 June 1885.

A very practical and profitable lesson, which is that if you want to acquire land or invest money in the most profitable manner, known as well to Melbourne citizens as to country folks with small capital, it is imperative to choose your land right in the locality to which a railway is certain to be constructed at a very near date. This is an axiom that every investor in land should fix on his heart and in his mind. [35]

It was not in the personal interests of Thomas Bent to support the extension of the railway to Picnic Point as he had land in Brighton which he wanted to sell and an extension of the line from Brighton Beach would open up unwelcome competition. Moreover, it was not in the interests of Brighton businessmen as an extended line would take visitors further down the bay and thus diminish their trade. Abbott on the other hand would benefit from the line’s extension because it improved the prospects of land sales with the finalised route crossing his land. To overcome ‘the long and exceedingly tedious delays’, it has been suggested that Abbott gained the support of Bent for the railway extension in return for his advocacy against severance. [36] Given the circumstances, Margaret Glass argues that Bent conceded the building of the railway in return for Abbott’s opposition to severance. [37]

Contract for the construction of the line was signed in May 1886 and it opened to traffic in September 1887. A short time before the opening of the line to Sandringham Abbott resigned from council and took an overseas trip with his family. His opponent, Harold Sparks, resigned a little more than three months later, creating a vacancy on Council in the West Riding. On Abbott’s return from Europe he was urged by an influential deputation to once again offer himself for election to council after his short retirement. Speaking at an election meeting held in the Duke of Edinburgh Hotel at Picnic Point in November 1887 Abbott indicated that while it was unwise to raise again the question of severance, given that it had recently been refused by the government minister, in one or two years it might be necessary as the shire became unmanageable. When that time came and the majority of local ratepayers were in favour of severance he said he would be with them. In the meantime he advocated sub division of the riding to give them more representation at the council table. Looking into future prospects he was convinced ‘the district must become a borough or even a city, in time’. [38] This response drew applause from his audience.

While the Brighton Southern Cross was not a supporter of Abbott in his 1887 re-election campaign but rather an opponent, the Editor wrote, ‘Should the electors desire to return to the old state of things, the old bickerings and quarrels, the old animosities, and the entrance upon a new and long course of unpleasantness, implied in the threats held out by the Picnic candidate at his meeting, they will know how to vote. If peace and quietness, and general efficiency in the representation are desired, they will also know how to vote.’ [39]

The opposition newspaper, the Cheltenham Leader, while acknowledging Vail and Hearle would make good councillors, gave strong support to Abbott. Mr Abbott needs no newspaper commendation. Actions speak louder than words, and his actions have been such as to claim the fullest recognition of the electors. The interests of the public are safe in his hands. [40]

Again he was successful, gaining a substantial majority of votes above his opponents to claim the vacant position created by the resignation of his opponent Harold Sparks. [41] A short time later when council elections fell due David Abbott once more subjected himself to the views of the ratepayers. On this occasion the Brighton Southern Cross expressed the opinion that Abbott would be returned and noted that he had filled the role of President of the Shire, had a large stake in the riding, had a liberal disposition and a solicitor’s knowledge. [42] From his re-election to council in November 1887 David Abbott served on the Shire of Moorabbin Council for a little more than ten years until his retirement in July 1898. During that period he was elected as president by his fellow councillors on two occasions; 1893/94 and 1894/95. He retired from council in July 1898 and clearly his view of severance for Sandringham had changed. As ex-Cr David Abbott he remarked that the importance of Sandringham had increased over the preceding few years yet the improvements made by council to the area were not commensurate with the rates contributed by that portion of the shire and ratepayers could see no other way of remedying the unsatisfactory state of things than by forming a separate shire. [43]

Aside from his work as a councillor David Abbott was a justice of the peace and a foundation member of the Royal Melbourne Golf Club when it was formed at a meeting held in May 1891. Seven years later the club acquired land near the corner of Victoria Street and Fernhill Road not far from Coggeshall with the links opening on 27 July 1901. [44] The club moved in mid 1931 to Black Rock onto land originally purchased by Josiah Holloway during government auctions.

After the sale of Coggeshall in 1909 Abbott’s address was listed at different times as the Australian Club in William Street, City, or 54 Cromwell Road, Hawksburn. In the year 1914 he was not listed in the Melbourne Directory. [45] During this time Abbott continued his work as a solicitor. Robert Beckett had joined the practice in 1889 and it was in January 1911 that he took over the assets and liabilities of the firm with David Abbott becoming a non-executive partner. Five years later Abbott retired with the intention to travel. [46]

Arriving in London in 1919 he and his wife toured around for a while and stayed with his married daughter, Elsie Maud Robertson, at Hastings, England. There he became sick and was admitted to the Buchanan Hospital where after this short illness he died on 29 September 1921 aged seventy seven years. At the time of his death his assets include two acres and eight perches of land in the Parish of Casterton together with several bank accounts, Commonwealth of Australia Stock, mortgages and five shares in the Royal Melbourne Golf Club totalling an amount of approximately £6716. [47] This was a modest estate considering he was at one time thought to be a millionaire. [48]

Abbott appointed his wife and daughter as executors of his estate and directed that they should equally share the five thousand pounds invested in Commonwealth of Australia stock, that his son Frank Walter Abbott should be discharged from repaying loans he had made to him, and the balance of the estate should go to his wife Emily Maud Abbott. However, she was to divide this balance amongst his three children in ‘such proportion as she thought proper’ either in her lifetime or by her will.

Footnotes

- The generosity of Shirley Joy in making available the results of her research is gratefully acknowledged.

- See, Whitehead, G., Josiah Morris Holloway: Pioneering Land Developer, Kingston Historical Website.

- General Register Office, London, Entry of Birth.

- Sutherland, A. Victoria and Its Metropolis: Past and Present, 1888, Vol 2 page 510.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 25 March 1882.

- Bradley, R., David Abbott, Mimeograph.

- Bradley, R., ibid.

- It is interesting that Matthew Henry Davies, the founder of Mentone was admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court on 23 March 1875 at the age of 25 years.

- Bradley, R., op cit.

- The Argus, 3 June 1893, page 12.

- Victorian Law Review 20, 1893-4.

- Bradley, R., op cit.

- The celebrant at the marriage was the Rev J H Gregory, the clergyman who laid the foundation stone at Dingley, Christ Church, was a friend of Mary Attenborough and the first vicar of All Saints’ St Kilda.

- Birth Certificates, Registry of Birth Deaths and Marriages, Melbourne.

- Certificate of Title – Department of Sustainability and Environment.

- Bradley R. op. cit.

- Defunct Companies Records, Public Records Office.

- Gibb, D. M. The Emergence of a Bayside Suburb – Sandringham c1859-1900, MA Thesis, University of Melbourne. 1971.

- Probate Records, Public Records Office.

- Certificate of Title – Department of Sustainability and Environment.

- Glass, M., Sandringham: By the Work of All, 2009, page 60.

- Certificate of Title – Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 5 July 1890.

- Minute Book 6, Shire of Moorabbin September, 1888.

- Sutherland, A. op. cit. Vol 2 page 510.

- See, Whitehead, G., Harold Sparks: Auctioneer, Accountant and Councillor, Kingston Historical Website.

- See, Whitehead, G., Protecting the Environment, Kingston Historical Website.

- Whitehead, G. Harold Sparks: Auctioneer, Accountant and Councillor, op. cit.

- See, Whitehead, G., Sparks Fly Between Harold Sparks and David Abbott, Kingston Historical Website.

- Southern Cross, 19 July 1884.

- Southern Cross, 17 January 1885.

- Whitehead, G., Sparks Fly Between Harold Sparks and David Abbott, op cit

- Glass M., Sandringham: by the Work of All, 2009, page21.

- See, Whitehead, G., I Know Where Beaumaris Is!, Kingston Historical Website.

- Gibb, D. M. op. cit. page 91.

- Southern Cross, 11 June 1887.

- Glass, M, The Sandringham Severance Movement 1884-1917, MA Thesis, Deakin University, 1988. See Chapter 4.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 19 November 1887.

- Brighton Southern Cross, ibid.

- The Leader, Special Edition , November 19, 1887.

- Votes Gained: Abbott 333, Vail 228 & Hearle 141.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 7 July 1888.

- Gibb. D. M. op. cit.

- Brighton Southern Cross, 30 November 1901.

- Bradley R, op. cit. page 68.

- Bradley R. op. cit. page 6.

- Probate Records, No 182-833, Public Record Office, Melbourne.

- Bradley R. reports that colleagues of Abbott thought he died almost penniless after at one time being a millionaire. Page 6.