Death at Cheltenham Railway Crossing and Call for Subway

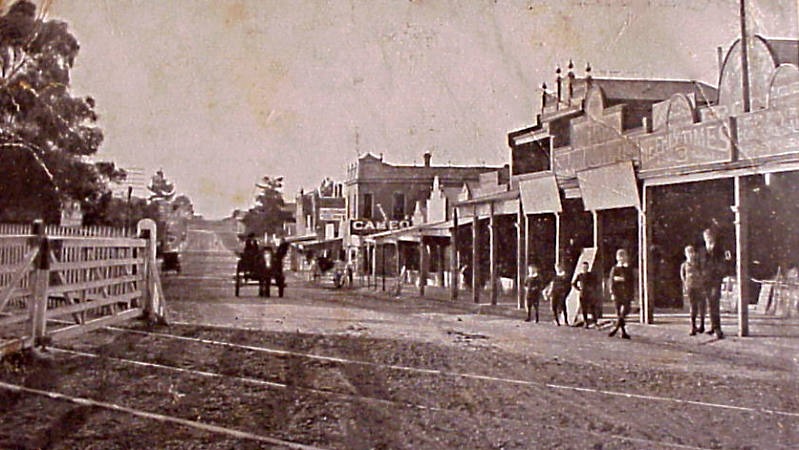

Charman Road looking north across the Cheltenham railway crossing, c1915. Photographer: Percy Fairlam Courtesy Betty Kuc.

The railway line from Caulfield to Mordialloc was officially opened by the Minister of Railways, Thomas Bent, in 1881. [1] The final route crossed many roads, creating a need for gates and gatekeepers to manage road traffic to ensure its safety and the safe passage for trains. Over the years many of these crossing have been the locations of fatal accidents despite the employment of gate keepers and later the installation of boom barriers for both road and pedestrian traffic. There was a heightening of concern in the local community of Cheltenham in 1898 when a young boy was killed by a special race train taking punters and friends to the Mentone races. [2]

Cheltenham State School, c1898. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

Harrie Long Mewett was the boy who was killed. His mother was Clara Long but his father was unknown. He lived with his foster father, Thomas Mewett, in Commercial Road, Mentone but attended the Cheltenham State School. The 1890s was when the prosperity of earlier time had dissipated, individuals involved in the development of Mentone had been declared bankrupt, and many of the houses of Mentone were untenanted. In this economic climate the Education Department authorities decided to combine the Cheltenham and Mentone Schools, with senior pupils attending Cheltenham or Mordialloc Schools. [3] Nine-year-old Harrie attended Cheltenham and it was lunch time on 14 December 1898 when he with other pupils of the school were playing near the railway line. Harrie and the two Cauldwell brothers, Eric and Clifford, decided to cross the railway line. An up train from Stony Point had just passed the crossing so the boys opened the unlocked wicket gate to get to the other side of the railway line. Initially they were unaware of the fast approaching special steam train on the down line. Clifford became aware of the approaching train and called out a warning. Eric got across but Harrie was hit by the buffer of the steam engine and carried twenty yards along the track. The train was stopped, the body of the boy with horrific head injuries was recovered, and taken to the gate keeper’s house. Dr Joyce declared him dead, saying his death was instantaneous. [4]

Steam Train, c1910. Courtesy Kingston Collection.

The train driver, Philip Augustus Seuling, who had years of experience driving, told the inquest that he sounded the train’s whistle continuously as he entered the Cheltenham station at about twenty miles per hour, rolling not steaming. He suddenly saw the two boys rushing through the small wicket gate when he was about fifteen yards from the crossing. All the gates were closed to traffic but the smaller gates were not fastened, and the signals were all in his favour. The train brakes were immediately applied but a tragedy was not averted. The gate keeper, Patrick Burke, confirmed the special train’s whistle was sounded continuously for a quarter of a mile and that school children were present near the line. When opening the gates to allow the passage of the trains he put a lot of boys outside the gates, and on returning to the other side of the line did the same thing for a number of girls. The wicket gates he said close automatically but although closed are not fastened and could easily be opened by a child.

The one issue on which the train driver and the gatekeeper disagreed was in relation to the ‘white flag’. Seuling told the inquest that the gatekeeper was holding up a white flag indicating that the lines were clear, a task that was part of a gatekeeper’s duty. Patrick Burke challenged this view, pointing out that he did not hold out a white flag for either train. While he admitted this was the practice some years ago he had not done it for some time as there were no regulations requiring him to do so. The coroner recalled the driver to respond to Burke’s comment. Seuling reaffirmed his view about the practice of holding a white flag citing Armadale station as an example, but went on to explain that his attention to the gatekeeper, standing almost one hundred and fifty yards away, would have been only a momentary one as he would have been concentrating on the signals and whether the gates were favourable to his passing. Moreover he agreed he might have mistaken some of the white dresses of the girls for the flag.

The inquest held at the Mentone Coffee Palace on 15 December 1898 before coroner J O’Meara, in the presence of a panel of five local men, after hearing the statement of witnesses, determined that Harrie Long Mewett’s death was accidental, being knocked down by a train while crossing the railway line at Cheltenham. John Butler was the foreman of the panel which included John Parson, Stanley Cullen, William Ross and Thomas McCaw as members. [5] Harrie’s body was buried in the Cheltenham Pioneer’s Cemetery on 16 December 1898 with the Rev J H Hill of the Mentone, Church of England conducting the service. [6]

Mentone Coffee Palace. Courtesy Shirley Joy, Kingston Collection.

A few days later, at a meeting of the Moorabbin Shire Council, Cr William Lamb Smith drew attention to the death of the boy at Cheltenham and reminded his colleagues that they had asked the Commissioner of Railways to provide a subway at Cheltenham. The need for a subway had been suggested by Dr Scantlebury a local medical practitioner. With the increasing railway traffic due to numerous race and pleasure trains passing over this crossing and the near presence of a school nothing but a subway was appropriate in the view of Cr Smith. Council he said had a responsibility to do something. He pointed out that the Railway Department had ‘spent £20,000 in spoiling their roads, and surely it could spare a trifling sum to prevent serious accidents.’ He moved that the council write to the Commissioner repeating their request for a subway.

Cr Penny, the president of the Shire, supported Cr Smith’s proposal but Cr McIndoe was more cautious. In his view consideration should be given to the necessary expense to achieve their goal. Moreover, he believed if a subway was granted to Cheltenham, Mentone, and Mordialloc, and numerous localities would ask for a similar concession. He said he had no sympathy with those who rushed the Commissioner for every little want. Despite his views the Smith motion was supported by the majority of councillors. [7]

Seven months later the president of the shire, Cr Penny, reported that several councillors had formed a deputation to the Commission of Railways, Mr Mathierson, and asked that a subway be constructed from Charman Road and under the station to the west side. On this occasion the reason given for such a construction was not the death of Harrie Mewett or the safety of Cheltenham State school students but rather the inconvenience to passengers for Melbourne caused by the ‘improvements’ made to the Cheltenham station. [8] The deputation and their views were courteously received by the Commissioner and he promised to send an officer to make an inspection. But in the course of his comments he asked what contribution was the Council prepared to make towards the cost of the subway. President Penny said this unexpected query ‘nearly took his breath away’. [9]

Cr Edwin Penny with family members. Courtesy E L Penny, Kingston Collection.

In August 1899 a plan for a subway was submitted to Council by the Railway Department with an estimated cost of £370. [10] The plan did not gain council approval so the president, Cr Penny was authorised to explain the reasons for its rejection to the Railway Commissioner. Subsequently, when reporting his meeting with the Commissioner he said the question of financial support from Council was again raised. When told the Council had not authorised him to commit any finance the Commissioner said his department would not entertain the notion of a subway unless the Council was prepared to pay one third of the cost. [11] At a subsequent meeting of council, a month later, correspondence was received from the Railway Department enclosing a plan of the proposed subway at Cheltenham with the estimated cost being £720, almost double that estimated two months earlier. [12] There the issue of a subway for Cheltenham rested for years.

Footnotes

- See, Whitehead, G, Official Opening of the Mordialloc Railway Station , Kingston Historical Website.

- Public Records Office, Victoria, 24/p/0000/698/1898/1565.

- Robinson, C., Additions and Subtractions, 1989.

- Public Records Office Victoria op. cit.

- Public Records Office Victoria op. cit.

- Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages: Certificate of Death.

- Cheltenham Leader, 24 December 1898.

- See, Whitehead, G, Cheltenham Station , Kingston Historical Website.

- Cheltenham Leader, 22 July 1899.

- Cheltenham Leader, 12 August 1899.

- Cheltenham Leader, 23 September 1899.

- Cheltenham Leader, 21 October 1899.