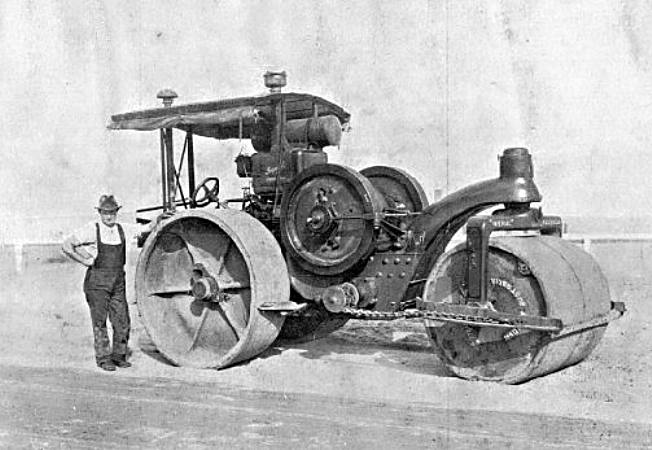

Municipal Roller

Steam Roller involved in road construction on Centre Road, Bentleigh c1925. Courtesy Helen Stanley, City of Kingston, Kingston Collection.

In the 1850s and later, colonial governments aware of the burgeoning financial burden of constructing roads through virgin bush delegated this responsibility to local elected groups called Road Boards; the beginning of local government. These Boards were given power to financially levy settlers and to charge road users tolls. Later these Boards became Shire Councils who continued to have responsibility for road construction and maintenance. [1]

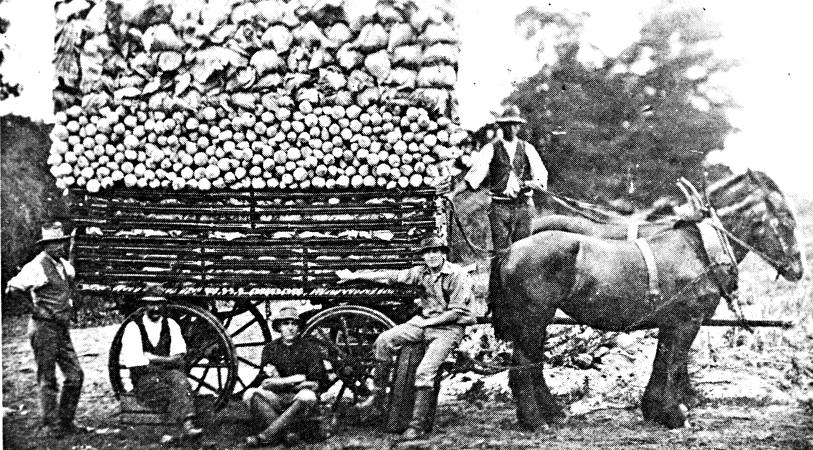

In 1909 Moorabbin councillors, aware that many of their roads had to bear traffic of heavily laden horse- drawn wagons taking produce to Melbourne’s markets, as well as other users , questioned whether the use of a steam roller in road construction would produce better roads. They instructed the municipal engineer to make enquiries and obtain prices and specification. [2]

Market gardener’s horse and wagon loaded with turnips and cabbages c1910. Courtesy City of Kingston, Kingston Collection

After the council decided to spend £700 on the purchase of a steam roller tenders were called. The colonial company Austral Otis Company of Melbourne was successful with its tender for a ten ton roller for £650.

Not all councillors were in favour of purchasing a roller. Cr Le Page thought the expenditure was unwarranted and the roller would become a very expensive ornament for the shire. A shed would have to be built to house it and a certified engine driver would have to be hired to drive it, he said. Crs Brownfield and White supported Le Page. Brownfield thought his ratepayers would ‘bump him out 2 to 1’ if he supported the proposal and White believed the roller would have nothing to roll but clay at Mordialloc. Cr Barnett saw no justification for a roller unless they had sufficient metal to lay on the roads. He said the ratepayers of the West Riding were always asking for metal but he always had to tell them council had no money. [3]

Cr Ferdinado was a supporter of the proposal as he believed a roller would make a big improvement. A roller, he claimed, would be especially important in the construction of new roads. There was already twelve months’ work for the roller in levelling side streets and the sides of water channels. Sir Thomas Bent was also a supporter. Bent advised his colleagues that the purchase of the roller would be one of the best bits of business they conducted. He told the Shire president that purchasing the roller was one of the grandest things the council could do under his reign. Cr Scudds pointed to the wasteful use of road metal that had been occurring during his seven years’ experience on council. He judged that fully one third of the metal that had been placed on roads had been scattered all over the place and wasted. This was a situation he believed would not occur with the use of a roller. [4]

When the time came to vote on the proposal the vote was tied. Six councillors voted in favour and six councillors against forcing the president to use his casting vote. Cr Scudds voted in favour with the successful tenderer undertaking to deliver the new municipal roller in two months.

A local reporter ‘waxed lyrical’ on the arrival of the roller in March 1910.

Last week the Moorabbin councillors were happy in the thought that no more would their wrath be raised by the continual upbraidings of the constituents, consequent on a ramble over the rocky roads of our shire. The medium of their happiness was the presence in the council yard of the new steam roller, an imposing £600 worth of glistening iron and steel.

The roller when resting peacefully in the yards, looked a model of high conception of the art of engineering, and councillors were jubilant over its embellishments, predicting great things.

On Monday, the engineer determined that the roller should be put through its paces, and gave the order to get up steam. Soon the glistening funnel of the monster was belching forth smoke and flames, and ultimately a hissing sound bespoke the fact that steam had risen. Then the driver was told to make all speed, regardless of speed regulations to the Watt Hill excavation, where the initial rolling was to take place.

Proud of his charge the driver got up into the cab of the roller and twisted a wheel. The engine gave an indignant snort, and then things began to happen. To the accompaniment of a long crescendo of snorts the fiery 13 tonner commenced to back its way out of the yard. Councillors stood by, awed with admiration. Back, back, back went the huge monster, the engine snorting defiance at the rattling roller. This machine had been standing in the yard since the last council meeting, and had probably taken the angry denunciations hurled by the councillors at the Mechanics committee, to heart, as instead of backing out the gate like a sensible roller the thing swung round and made a bee-line straight for the small kennel that marks the locality where the library exists. With a bound and many snorts the monster tore down on the unsuspecting ‘dog room’ but just as annihilation seemed imminent a roar and a clank sounded, and the horrified councillors opened their eyes to find IT standing still, glowering down on the hall like the villain in a penny dreadful, and presenting a tableaux that spoke volumes on the rights of some things.

After such a deliberate attack on the bone of contention, the monstrosity allowed itself to be snorted down to Cheltenham. On the road down many fiery steeds endeavoured to look down the funnel of the engine while cows and calves, to say nothing of sundry scared fowls, careered down the road with tails flying, and owners swearing. After an eventual fun, the roller, escorted by all the small fry of Cheltenham, duly arrived at Watts Hill, and with a wonderful rattle climbed on the metal and rolled up the hill. When on the top it looked imposing, but when it reached the bottom it looked ridiculous. The reason is not plain, but on its return journey the roller bolted, bucked or shied, with the result that its great heavy wheels slipped off the road, and plunged into the soft sand and clay. Kids made one lightning sprint for home and beauty, while sundry councillors and others showed marvellous agility in scaling an adjacent fence. But much haste was needless, as in the sand the roller stayed, despite the efforts of a sweating gang of men and a succession of snorts from the indignant engine.

Numerous devices were made to shift the monster, but the efforts of the men were as helpful as so many flies. As night fell the roller was still stranded, and after being tied up with a tarpaulin the cause of the worry was left to the mercy of the stars. Morning light brought forth a small army of workers armed with screw jacks and a varied of timber, but some hard work and some tall talk was all that eventuated, night again finding the roller still stranded. Next day however, brought about a change, the roller being shifted to the roadway again. Since then matters have rolled on smoothly and when last seen the roller was gaily snorting its way down in the direction of Mordialloc, and judging by the absence of contra report, Mordialloc still appears in existence.

The people of Cheltenham were pleased to see the roller enter the town, but were still more pleased to hear it depart, as living in hourly expectation of a 13 ton roller climbing through the side of your house and upsetting your cup of tea, does not tend to pleasant reflection. [5]

The roller performed satisfactorily the next week in Mentone and Mordialloc but then defied the driver to slunk into the gutter of Florence Street, Mentone refusing to move. The Argus reported that the whole of the council’s daymen were engaged with screwjacks to free the monster. [6] This report was described as inaccurate by the engineer , nevertheless it stimulated the argument once again that the roller was too heavy for the local roads with Crs Le Page and White reminding their colleagues of their prophesy.

The episode also caused Pic and Coffee to write of his indignation at the enormous expenditure invested in the huge piece of ‘uselessness’ but suggested it could be located near Cheltenham as a pie and coffee stall. There gardeners, he thought, could make a brief respite on their weary road to market. [7]

Seven years later the roller was again an item of discussion amongst councillors. Cr Rogers believed the roller was a ‘dead loss’. Moorabbin, in his view, could not afford a white elephant of such dimensions. The president, Cr David White was in agreement. He voted against the original purchase, and as he understood the main roads had been constructed it was better to sell it rather than having such an expensive piece of machinery lying idle. [8]

Old steam rollers at a local rally. Courtesy Mordialloc and District Historical Society.

While another five years passed with the councillors still considering selling the roller, it had leased it to the Country Roads Board for £1 per day. [9] Subsequently it was reported that the roller was not considered serviceable and was too costly to repair. The assistant engineer recommended that the council purchase a secondhand 8 -10 ton motor roller that carried a six months guarantee for £750, a saving of £600 on the cost of a new machine. After a lengthy debate the recommendation was adopted. [10]

City of Mordialloc Motor Roller 1926. Courtesy City of Kingston, Kingston Collection.

Footnotes

- The Moorabbin Road Board was established in 1862.

- Moorabbin News 6 March 1909.

- Moorabbin News 10 July 1909.

- Moorabbin News 10 July 1909.

- Moorabbin News 5 March 1910.

- The Argus 2 March 1910.

- Moorabbin News 12 March 1910.

- Moorabbin News 8 December 1917.

- Moorabbin News 24 June 1922.

- Moorabbin News 12 January 1924.