Prisoners of Japan

As the Japanese army moved swiftly down the Malaysian Peninsula to capture Singapore in seventy days concluding on 15 February 1942, thousands of Australian troops, together with members of the Indian and British forces, were taken prisoner and incarcerated. Other Australians were captured by the Japanese at Ambon, Java, and Timor while some were taken at sea. The Australian soldiers who were members of the Gull Force, arrived in Ambon in December 1941, faced the Japanese In January 1942 and surrendered on 3 February 1942. Eight hundred surviving solders were made prisoner. Other Australians landed in Java when returning to Australia from the Middle East. Joining Dutch troops, they faced the Japanese but were forced to surrender with over 2,700 becoming prisoners. At Timor the story was much the same. Dutch and Australian troops initially resisted the invasion of the Japanese but were forced to surrender with more than a thousand individuals becoming prisoners. At sea a number of Australian, Dutch and American ships were sunk resulting in loss of life, but some sailors were saved only to be made prisoners of war. [1]

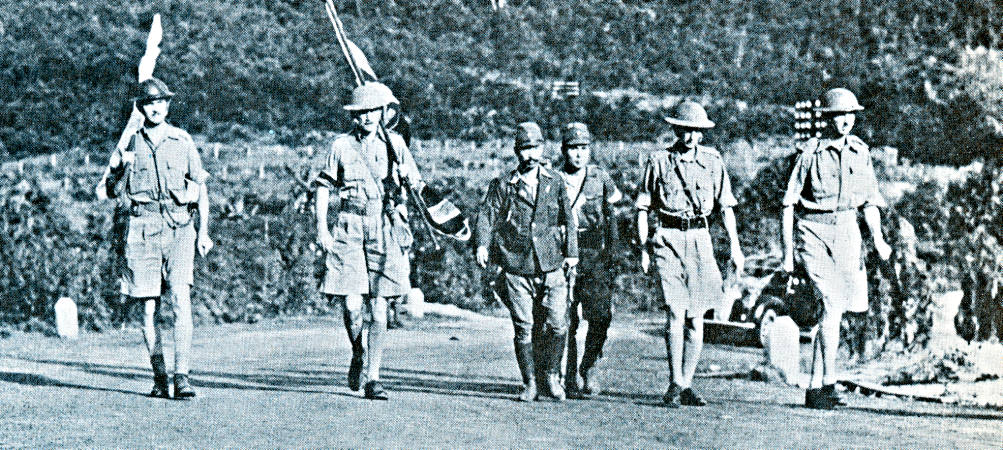

Surrender of Singapore to Japanese. British Army Officers walk with Japanese victors, 1942.

Back home many families did not know what had happened to husbands, sons, and friends. Often after long delays, information was gained and official letters were dispatched to parents or wives. These official acknowledgements were sometime published in local newspapers. The detention of Captain Rogers in Singapore in February 1942 was noted in the Mordialloc News in January 1943, while in April of that same year Norman Adlington’s internment in a prison camp in Borneo after the fall of Singapore was noted. [2] It was in this context that appeals were made to the community for contributions to the Red Cross Prisoners of War Fund. The Australian Branch of the Red Cross had committed itself to a weekly expenditure of £38,000 to support the program of aid to prisoners of war.

In May 1943 the City of Mordialloc ARP (Air Raid Post) Social Committee decided to hold a dance in the Mordialloc Masonic Hall. Fred Holland and his band provided the music while other artists gave their services to entertain between dances. All this with no cost! Supper was provided by the local Red Cross and the First Aid Post. [3] The only expense not covered was the rent of the hall and this was later paid with an anonymous donation. A profit of £60 was a fine outcome for a worthy cause and an excellent evening which gave residents the opportunity of enjoying a social evening with friends. More events followed.

Football enthusiasts were invited to watch a match between a combined local under-18 team and the Kittens from Richmond. The attendance of several prominent Richmond players, including Jack Titus and Jack Dyer was an added attraction. Admission was free but a collection was made for the POW funds. [4]

In December 1943 Minnie Everett staged her Children’s Christmas Show at the Mordialloc City Hall. The show sponsored by the City of Mordialloc ARP was in aid of the Red Cross Prisoners’ of War Fund. It drew a crowded house and the local newspaper reported it was worthy of the large audience. Most of the performers were making their initial bow before the footlights, and acquitted themselves with honours, the reporter noted. Between £25 and £30 was raised for the fund. [5]

By the end of February 1944, £1268 had been raised by the City of Mordialloc Red Cross to provide some relief to approximately fifty local men in the hands of the enemy. It cost £50 per annum to keep each man supplied with a parcel that supplement the meagre fare provided by his captors. The aim was to raise £2500 by June.

At the end of the war in the Pacific Australian prisoners of war were widely distributed. In Singapore Island and Johore there were 5,549, Burma and Thailand 4830, French-Indo China 265, Java 385, Sumatra 243, Ambon 100, Macassar 2, Bali 7, Kuching 150 and 2,700 distributed between Japan, Korea, and Manchuria as well as 200 on Hainan Island. [6]

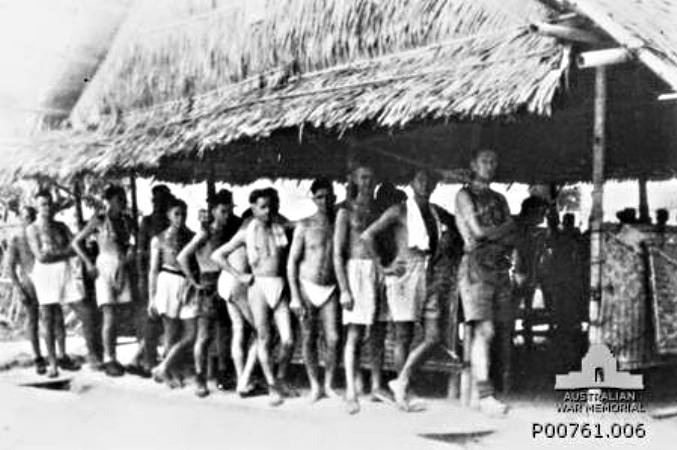

Burma Thailand Railway. Prisoners of war queuing up to wash at a camp along the railway. Donor A Mackinnon, Courtesy Australian War Memorial P00761.006

Jim Brown of Cheltenham wrote to his parents describing his experiences of being part of a rescue team sent to free Australian prisoners of war in Kuching. The team consisted of about 200 troops drawn from each unit in Borneo. It was given the task of ‘fixing up’ the POWs , then disarming and interning 5000 Japanese in the city, ‘along with other jobs’. He said he was lucky to be part of the team. On arrival in Kuching he found himself involved with evacuating POWs and civilian internees to hospital. Some of the fitter ones were put on boats to be taken downstream to the open sea where a hospital ship and others vessels were waiting to take the prisoners back to the big hospital at Labuan Island off the coast of Borneo.

Australian prisoners of war from Ambon. Courtesy State Library of Victoria. Image H98.103/370

Jim went on to write,

‘I guess you will be wondering in what condition were the POWs. Well folks, it is something I’ll never forget, but I’d like to and I’m afraid I can’t describe just what I’ve seen, except to say that with the exception of a few, they were physical and mental wrecks and a pitiful sight. When I tell you that men who are over six feet high weigh only 3 stone, it will give you some idea of their condition. From the time we first entered the river to proceed up here, we were given a rousing welcome as we passed each native village along the river. On arrival at the wharves here, we found the whole of the natives waiting for us, cheering, waving flags, and really a marvellous reception. As we disembarked we were surrounded by every class of native, wanting to shake our hands, carry our kit-bags, offer us fruit; in fact, a grand reception, but it would take a long time to describe it all.

We were marched through the streets to the hospital, where we are camped, and immediately set about preparing for the POWs. That completed, we went to the compound, and it was worth a year or more of our lives just to see the looks and expressions of the Aussies and Tommies when we marched in. The ones that could still walk just threw themselves upon us and then broke down, but the poor devils who were too weak to move, well, I just can’t describe their reactions, and I’m sorry to say that for some the shock and excitement was too much for them, and it’s hard to think that they lived only long enough to know that they were free, after all they had gone through.’ [7]

On arrival home prisoners of war faced the tumultuous welcome from relatives and friends. Sapper Len Kealy in speaking of his future plans said he intended to do some chicken raising as it was about the only way to secure enough supplies to satisfy his appetite after his three and a half years of incarceration. [8] Sgt Norm Halliday, a prisoner in Burma and Thailand, described his treatment as inhuman but after liberation had put on two stone in weight. L/Cpl Cecil Rowsell made similar comments about his treatment as a prisoner. For Private Les Kerr, following his imprisonment in Changi (Singapore) for three and a half years, he was sent to work on the railway in Thailand. At Changi he thought he was reasonably well treated but when transferred to Thailand he said it was the worst and it was the efforts of the medical officers that kept men alive. On arrival back in Melbourne he was transferred to Heidelberg Military Hospital with mild malaria but made a quick recovery. Since his release he too has put on weight. [9]

Courtesy: Argus Melbourne, State Library of Victoria H98 103/366

Footnotes

- www.ww2australia.gov.au/japadvance

- Mordialloc City News, 2 April 1943.

- Mordialloc City News, 14 May 1943.

- Mordialloc City News, 25 June 1943.

- Mordialloc City News, 7 January 1944.

- http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/pow/ww2_japanese/

- Mordialloc City News, 15 October 1945.

- Mordialloc City News, 18 October 1945.

- Mordialloc City News, 15 November 1945.