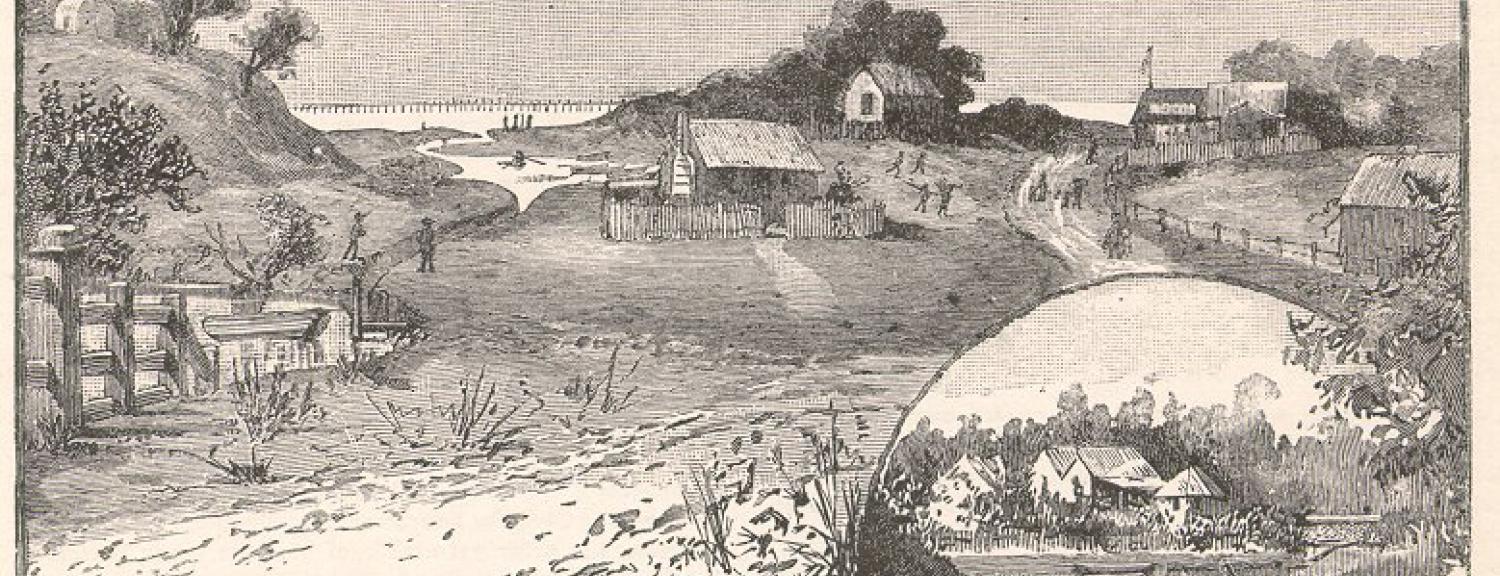

Mouth of the Mordialloc Creek with the Bridge Hotel in the distance and the sports ground on the left.

Date:

1910

Courtesy:

Ida Reynolds

Collection:

Kingston Collection, City of Kingston

Mordialloc Creek 1888, Sutherland, A.,Victoria and Its Metropolis, Kingston Collection.

Mordialloc Creek was an essential element in the natural drainage of the Carrum Swamp, taking excess water to the bay. 1The estuary of the creek was also an important habitat and breeding site for a variety of marine life. The Bunurong people had been living in and moving through the district for tens of thousands of years, attracted by the abundant food and rich resources available.

With the arrival of colonists the creek provided a safe anchorage for boats and a place of settlement for fishermen. In the late 1850s there was a regular canvas town of fishermen’s tents and between forty and fifty boats at one time at Mordialloc. There were also Chinese fishermen netting small fish which they smoked and sent to their Chinese friends on the gold fields. 2

Mouth of the Mordialloc Creek with the Bridge Hotel in the distance and the sports ground on the left.

By the 1880's the silting up of the mouth of the creek became such an irritating problem to users that the Moorabbin Shire Council called upon locally elected parliamentary representatives to draw the notice of their colleagues to the issue. 3 Despite this call, it was a problem that remained an issue for well over a century. In 1890, a local newspaper, while acknowledging the population of the place was very limited, pointed out that the colony depended on the fishermen’s supply of fish in turn the fishermen needed a safe shelter for their boats. 4A few months later at low tide it was impossible to take boats from the bay into the creek. 5

Several years later, in 1906, a correspondent to the Moorabbin News bemoaned the fact that a boat drawing over two feet of water could not enter the creek because the whole of the entrance was blocked with mud and stone. He proposed that the mouth of the creek be widened to three times its existing size to allow a good outflow, and the whole creek be dredged to seven or eight feet. Arising from this action he believed the number of pleasure boats, yachts, and motor boats visiting would benefit the commercial community while attracting professional and amateur fishermen to one of the prettiest places on that part of the coast. 6

Jack Pompei standing on a sand bar at the mouth of the Mordialloc Creek.

The Mordialloc Progress Association was at odds with the suggested widening and pointed to the mess made by the government’s widening of the creek above the railway bridge. A most picturesque portion of the creek, in their view, had been widened into a drain with precipitous sides and twelve feet of mud banks at low tide. If this approach was continued on other portions of the creek, the Association claimed, the creek would be robbed of its charm. 7

The matter was still in contention two decades later when a public meeting convened by the Mordialloc Boat Club in 1925 attracted the attendance of councillors from the Town of Mordialloc and the Borough of Carrum as well as local politicians. The Mayor of Mordialloc, Cr Bradshaw, said the aim of the meeting was to discuss ways and means of getting some improvements to the mouth of the creek which had silted up. To his mind it was a government matter.

Parliamentarian, Mr Frank Groves MLA, said sufficient money had been wasted on the creek to pave the entrance with gold but warned if anything was to be done in the future all local governments had to contribute. Nothing would be done if the government had to find all the money, he said. In making this statement he severely criticised the shopkeepers of Mordialloc for their absence from the meeting as, in his opinion, they too had much to gain. Cr Edwards spoke forcefully in a fighting presentation saying the foreshore was a national asset belonging to and being patronised by all the inner municipalities, implying it was a government responsibility. He told the audience the Mordialloc Council was prepared to go to the government and demand that something be done. This comment generated cheers from the audience. 8

In 1926 the government promised to implement a permanent solution at the entrance to the creek provided the local community matched its contribution of £1000. This the community did. The Mordialloc Boat Club offered £500 while another £500 was made available from the proceeds of the Mordialloc Carnival. Unfortunately, before the scheme could be implemented the government fell.

The new government, rather than continuing with the project, cancelled it, claiming it had no money. 9 In a letter to the local newspaper, B. Shelley, the secretary of the boat club, emphasised that the people of Mordialloc had played their part in giving up holidays and working at the carnival to raise funds to carry out public works that should be, in his opinion, completed by the government. Pleasure boats and boats owned by persons who earn their living by fishing were tied up in the creek unable to get out except at high tide. This sometimes meant a wait of twelve hours to get back in again. Shelley went on to warn that the condition of the entrance to the creek could result in the loss of life during a storm. He also pointed to the danger resulting from drainage. Nearly all the drainage from Mordialloc, Parkdale, Mentone, Cheltenham and surrounding districts was conveyed to the creek creating a hazard if it was blocked from reaching the bay. 10

For some years professional fishermen had complained about the entrance to the creek and conditions along both banks. Large sums of money had been spent indiscriminately to no identifiable effect. Indeed, it was thought that conditions had significantly deteriorated. Many individuals felt the problem was that too many public departments had a say in the management of the creek resulting in no action. A newspaper reporter expressed it as ‘what is everybody’s business is apparently nobody’s business’. Ports and Harbours controlled the mouth, the State Rivers and Water Commission controlled the stream, while the banks were the concern of the Lands Department. It was too difficult, he said, to arouse these departments from their Rip van Winkle-like sleep. The two councils, Mordialloc and Carrum, realizing the existing inertia, dropped an earlier plan to gain control of the creek. 11

Four years later, in 1929, councillors from Mordialloc and Chelsea met the Minister of Public Works to argue that control of the Mordialloc Creek should be vested in the Mordialloc Council. The Chelsea Council agreed to this, provided that all moneys raised on the creek through moorage fees were spent on the creek. The Minister, Mr Chandler, who thought their arguments were unanswerable, said he would seek advice on the legal implications and would grant their request if possible. 12 In 1931 the Mordialloc Council was appointed the Committee of Management under the Lands Act for all that section of waterway downstream of the railway bridge. In 1958 Council control was extended upstream to approximately the J Grut Reserve.

In 1934 the creek, like the Carrum Swamp, experienced stormy weather and flooding. The Mordialloc Creek, the only drainage outlet for the whole of the municipality, was banked up by the tide and quickly overflowed into many houses along its upper reaches and surrounded them with water. 13 Sixteen boats were swept out of the creek estuary and smashed to pieces. The baths, the pier and the carnival Jazz Dance Palais were wrecked. Water flooded across Point Nepean Road. 14

Mordialloc Creek in flood, scallop fishing boat moored.

Flooding again occurred in 1952. There was fast flowing water on land abutting Chute Street and at the east end of McDonald and Bear streets. At one stage boats were caught under the bridges, and several had been washed through the mouth of the creek and cast up on the sand between Mordialloc and Aspendale. It was estimated that between thirty and forty boats were sunk or damaged. 15

After the flooding of the fifties calls to improve the condition of the creek and the efficiency of its management continued into the seventies. Jack Pompei, whose family had been working on the creek since the 1920s, was a boat builder and advocate for the creek. His view was if you take the creek out of Mordialloc there would be nothing there. He spoke of the time when there would be 88,000 people at Mordialloc having picnics and enjoying the beach and creek. There were six passenger boats that would bring people to the Mordialloc pier. There were twenty fishermen tying up their boats in the creek. People enjoyed the creek because it was full of fish. Severe flooding in 1934 had brought about a drastic change, according to Pompei. A decision was made to block the winding creek and in the years that followed silt and pollution built up; fish disappeared; the murky stretch of water became so badly fouled that people were warned that swimming there was dangerous. 16

Jack had a plan to bring the creek back to life. He proposed extending the mouth of the creek to the end of the pier and to curve it around to the deep water, to prevent is being choked up with sand banks. He said Mordialloc had the safest port and the worst entrance. Put in silt traps, replant the red gum trees that produce durable wood and dredge once every three years. Put a drag line through the creek and dredge it to Carrum. He envisaged people living at Aspendale Court could use a boat to go shopping but warned that the top end was silted up with boats sitting on mud. 17

Drawing showing Jack Pompei's proposal for the development of the Mordialloc Creek.

By the 1970s the environment of the Mordialloc Creek continued to be of concern to local people. The Mordialloc Beaumaris Coastline Conservation League undertook an environmental study of the creek, the results of which they presented to Mordialloc Council. The League wanted the visual environment of the creek sensitively landscaped after noting the unsightly nature of the industrial development to the north and the untidiness of the residential area to the south. They suggested the possibilities of a boat harbour, picnic areas, creek sidewalks, a wild life reserve, an aquarium and community facilities but they realised the financial requirement was beyond the capacity of the municipality. The spokesman for the League, Mr Iggulden, said the creek had to cease being a polluted drain and be developed as a community asset. 18

Through the 1970s the creek drew politicians and would-be politicians to survey the condition of the creek and to listen to and receive petitions from local residents and organisations. Alan Hunt, the Minster of Local Government, saw the answer to polluted drains and creek as establishing one authority which would lay down a plan of action in which all the others must participate. He said that ‘with 15 authorities with a finger in the pie it was impossible to reach a decision.’ Mr Dunstan, Minister of State Rivers and Water Supply, agreed with his colleague Mr Hunt on the ‘one boss’ idea. He said sullage, septic run-off and industrial waste were the main pollutants in the Mordialloc Creek and these were accentuated by the natural silting at the mouth. He believed the big mistake was made seventy or eighty years previously when the waters from the Dandenong Valley catchment area were drawn away from the creek and diverted down the Patterson River. 19

Labour candidate for Chelsea, Michael Duffy, standing in the Mordialloc Creek pointing to the polluted sediment.

In 1976, after a deputation of two Mordialloc councillors and the city engineer met with the Premier, Rupert Hamer, Councillors Michael Buxton and Peter Scullin thought they had achieved a permanent solution to the problems of the creek. The government was to provide $750,000 to clean the entire length of the creek and install silt traps to prevent further sediment entering the creek, and to landscape the surroundings. There was also a plan to re-wall the boating areas of the creek. Complementing these actions was the divergence of sewerage drains from Braeside and Heatherton to the South Eastern Sewerage Purification Plant. Cr Buxton hailed the proposed actions, seeing them as the first time that anything of lasting benefit has been identified. ‘Concentrating on water quality is important, but the main issue is that we have achieved a great breakthrough in cleaning up the creek,’ he said. 20

But only three years later old complaints re-emerged. The President of the Mordialloc-Beaumaris Coastline Conservation League lamented the fact that the government’s $750,000 which was initially provided for creek work, was spent on increasing its effectiveness as a drain. At the same time University reports found that the Mordialloc area contained a large number of notoriously polluting industries - electroplating, yarn dying and paints and lacquers - most of which discharged waste through the drains into Mordialloc Creek. 21

Dr Brian Robinson, chairman of the Environment Protection Authority, said in 1994 that the water of Mordialloc creek would become noticeably clearer when the sewerage outfall from the Dandenong Treatment Plant was stopped. The effluent being discharged into the creek was to be diverted to Carrum. This situation had been allowed to continue because of the cost and the existence of other priorities. The biggest priority in the seventies and eighties was getting the area sewered. While Dr Robinson said the creek would never be a pristine, bubbling mountain stream, he hoped it would become something that people could enjoy.

Aerial view of Mordialloc Creek taken during Moorabbin Air Show Promotional flight.

Schemes or strategies for dealing with the creek continued to be proposed into the twenty-first century. In 2011 the City of Kingston, being the ‘Committee of Management’ from the creek’s mouth to the railway bridge developed a dredging program strategy. 22This was done with the cooperation of Melbourne Water which managed the creek upstream as a drainage course, and Parks Victoria which was responsible for the mouth of the creek and the pier. (The notion of ‘one boss’ for the creek spoken of in the 1970s had not eventuated at that time.) The issues addressed in the plans included managing boat movements, identification of ‘hotspots’ of pollution, fees for commercial use of upgraded infrastructure, boundaries and clarification of management and the long term management of silt and pollution. 23 This plan provided a way forward to the achievement of a vision many individuals had spoken of for the creek over the past fifty years.

©2026 Kingston Local History | Website by Weave

City of Kingston acknowledges the Kulin Nation as the custodians of the land on which the municipality is a part and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. Council is a member of the Inter Council Aboriginal Consultative Committee (ICACC).