Horse Trams From Cheltenham to Sandringham

Horse drawn tram of the Beaumaris Tramway Company.

The availability of reliable regular and frequent public transport was very important to the land speculators of the 1880s. With it land sales were stimulated and the possibility of great profits from land sub divisions and sales were more likely. This need for public transport, in many instances, was met by the presence of government funded railways but in situations where the railway was not available the answer was privately owned tramways. With the approval of the municipality any land owner could form a company to provide the transport that made their land more attractive to purchasers.

Charles H James, an early land speculator, had large holdings in the Shire of Moorabbin at Black Rock, Sandringham and Mentone. In 1884 he was advertising the auction of 109 blocks of land at ‘Picnic Point’ in the Brighton Southern Cross.[1] He provided free railway passes and conveyance to the grounds to prospective buyers. In addition to the land which he personally owned he was heavily committed financially in several land companies with large holdings in the district. These included the National Land Company, the Colonial Investment & Agency Company, the Freehold Investment Company and the Southern Investment Company. [2]

A proposal to extend the Brighton Railway to Sandringham and Black Rock seemed remote in 1884 so James acted to resolve the lack of public transport by forming his own tramway company. He responded to the decision of the councillors of the Shire of Moorabbin to grant any bona fide company permission to build a tramway from “the proposed Picnic line towards Mordialloc” by writing a letter expressing his interest. [3] A committee of the Council consisting of Councillors Bent, Comport, Ward and Abbott was formed to discuss the matter with him. [4] James then proceeded to register the Beaumaris Tramway Company on December 3, 1886. The Articles of Association noted him as holding one thousand shares, and his fellow investors as being David Munro, contractor; George Sutton, gentleman; John Hamilton solicitor; George Thomas Langridge, auctioneer; Robert Malton auctioneer; and Harold Sparks auctioneer, all holding three hundred shares with the exception of Malton who had five hundred.[5] Almost all these participants were potential benefactors from any increase in land values and sales in the area arising from improved access to public transport. A couple of years later Cr Daly said it was only a ‘sham company’ set up so the participants could sell their land. “They were playing a high handed game.” [6]

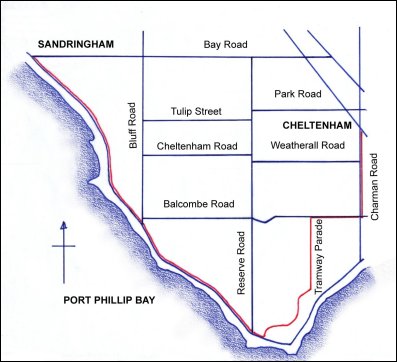

From the discussion between the Council and James it was agreed that the Council would apply for permission to construct a tramway on Beach Road. It was to be constructed in three stages. The first section was to be built from Bay Road to Balcombe Road within nine months of obtaining the order. The second stage was from Balcombe Road to Cromer Road in eighteen months and from there to Mordialloc in three years. Charles James was to bear all costs.[7] More than a year later a notice was inserted in the Government Gazette and the Brighton Southern Cross declaring the Council was about to make application to the Governor-in-Council for authorisation to build a tramway. The route however was to vary from that previously discussed with James. Section A was to commence from Cheltenham railway station rather than Picnic Point and to finish at Rickard’s Point.(sic) The starting point for Section B was the junction of Bay Road with Beach Road and was to finish at Rickard’s Point. Mordialloc to Cromer Road was the third section.[8]

Route of the horse trams.

The conditions stipulated in the draft agreement between the Tramway Company and the Council indicated that Sections A and B were to be completed within 12 months and Section C within 36 months. The company was to pay a deposit of £1500 which they would forfeit should they fail to construct any of the sections. After 21 years the stock, buildings etc were to be sold to the Council.[9]

The Governor in Council gave approval in July 7, 1887 for the construction a tramway in the Shire of Moorabbin but it took some time before the Council delegated this authority to the Beaumaris Tramway Company. Sticking points in the signing of the agreement were the requirement that the Company pay a bond of £1000 and the wording of one clause concerning the transfer of rights, privileges, goods and chattels of the company.

Cr Abbott, a solicitor by profession, a land owner in Sandringham and an influential voice on Council was an early critic of the tramway proposal. He was berated by a reporter in the Brighton Southern Cross for focussing on Charles James in the argument. The reporter believed Cr Abbott was doing this to gratify personal animosity. (James was a strong advocate for the severance of the Sandringham/Black Rock area from the Shire of Moorabbin whereas Abbott initially opposed the move.). After all, the reporter pointed out, Mr James, was a ‘high minded and honorable gentleman’ representing a large constituency in the Legislative Council.[10]

As time went on Abbott and other councillors became more frustrated with the inability of the Council and the Tramway Company to reach agreement Ultimately it was Abbott who proposed that the Council sign the agreement of delegation giving the Tramway Company the right to proceed with its plans. When moving the appropriate motion he indicated he had never opposed the tramway pure and simple but he had insisted on a proper agreement being entered into between them. He claimed he had been subjected to a lot of insults, and lies had been attributed to him, Now the agreement had been properly prepared he was proposing the necessary motion for delegation. [11]

Charles James wrote in his first report as Chairman to shareholders in the company in December 1887, “After prolonged negotiations, the Moorabbin Shire Council have signed the contract delegating the Government Order giving power to your Company to construct lines … for a period of 30 years from Pic-Nic Point Railway Station to Rickett’s Point thence to Cheltenham and Mordialloc.” He pointed out that the first section of 2 miles 37 chains from Cheltenham to Rickett’s Point was in operation and they were working on the second section. [12]

By February 8, 1889 the horse drawn trams were running from Cheltenham Station to Rickett’s Point and from Sandringham Station to ‘Blackrock Corner’. Six months later, in his half yearly report to shareholders, Charles James announced that the tramway from Sandringham to Cheltenham was “in full working order”.[13] Stables had been built at Beaumaris and Black Rock and the company, he claimed, was now ready for “large and extended traffic” particularly in the coming summer. In addition to the tram depots between Love and Eliza Streets Black Rock and Oak Street, Beaumaris the company had 25 acres of land between the present Oak and Pellatt streets, Beaumaris where oats was grown and chaff cut to feed the horses that pulled the tram cars. [14]

Beaumaris Tramway Stables. Courtesy of Sandringham and District Historical Society.

Fairlie Taylor described the horse drawn trams as cumbersome conveyances with seating accommodation inside and above. “The favourite spot, of course, was above, and to reach this you climbed a spiral stair way. Mr Milner was the Manager, and his son George drove the trams. When the trams ran off the lines, passengers had to scramble out and help to move them back. The driver had a specially long whip which he used round the legs of local children who loved to ‘cling on’ behind for a free ride.” [15] There were both double and single decker trams drawn by two horses although with the larger trams three horses were used. The driver was responsible for collecting fares and supervising the behaviour of passengers.

The rules and regulations of the company indicated that passengers had to enter a carriage from the rear and no more than four passengers were permitted to ride on the conductor’s platform or obstruct free use of stairs. No smoking inside or on stairs. No playing of musical instruments without permission. No person in an intoxicated state was to be admitted but if they should succeed they were to be ejected. Swearing and obscene or offensive language was forbidden. Any person whose dress might in the opinion of the conductor soil the dress or clothing of another passenger was to be denied entry. These rules were amongst twenty one approved by a Council meeting held on July 7, 1890. [16]

There was also a list of seventy rules that applied to drivers. Drivers were expected to drive at a uniform speed at all times and if delayed could urge the horses to move at a fast trot but galloping was barred. Should their way be obstructed they were to ring their bell and ask the offenders in a pleasant voice to clear the track. At all times they were to be polite, patient and civil to passengers but were warned that there were to be no free rides, everyone had to have a punched ticket. The exception to this rule was the Manager, pass-holders and employees wearing a badge or cap. They should also be cautious not to accept foreign coins or English coins with holes and when collecting fares should call out distinctly ‘fares ready please’. Should a passenger ignore the request they should not touch him to attract his attention but speak again.[17]

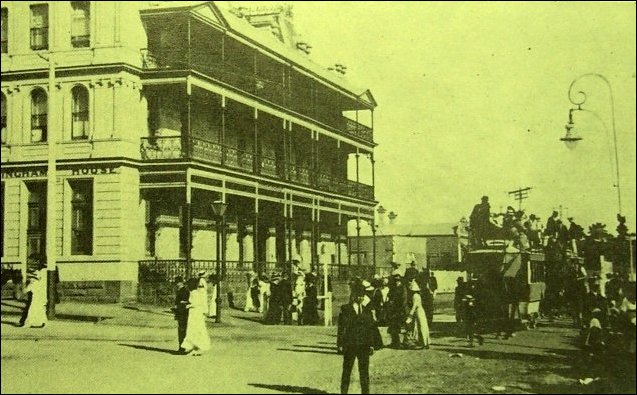

Horse drawn trams outside Sandringham House in Beach Road, Sandringham. Courtesy of the Sandringham and District Historical Society.

People expected the operation of the company to be a financial success. Chairman James reported to shareholders in 1889 that £1007-11-11 had been taken in fares since the tramline was opened and saw this as a predictor of a bright future. [18] The cooperation of the Victorian Railways in issuing a ‘Circular Ticket’ allowing passengers to travel for two shillings from Melbourne to Sandringham and from there by tram to Cheltenham, returning to town via Cheltenham was considered a major step forward in achieving profitability.[19]

Despite positive expectations of directors and shareholders, and the comments of observers the financial success of the Company did not eventuate. The company had made a large financial commitment to establish itself. The construction costs were £12,790-19-10, horses £417-1-10, real estate £2,694-7-0 and cars £2933.6.0. [20] Against this capital investment the returns at best were meagre. The Income and Expenditure statements detailed in the six monthly reports invariably show an excess of expenditure over receipts. There are instances, such as in August 1898 when receipts are given as £660-3-11 and expenditure as £608-12-6 but £204-9-11 in interest payment was not included. The June Report for 1906 lists income from fares as being £1058-11-9 against working expenses £975-9-3, general expenses of £83-19-5 and interest payments of £220-14-6. Often explanations accompanying the statement of income and expenditure point to bad weather during important public holidays and dull weather over the summer period influencing the number of customers on the line, cost of horse feed, increasing expenditure because of repairs to cars caused by the increased mileage over which they had to operate and the general state of the economy. The major depression of the 1890s no doubt had an impact on population growth and land development and sales in the area.

Ultimately the financial situation was probably a major reason the company failed to complete its original obligation of constructing and operating a tramway to Mordialloc, although early in the discussions some councillors expressed the view that the company never intended to take the tram from Cheltenham to Mordialloc. [21] Nevertheless councillors drawn from the southern portion of the Shire continued to press for the original agreement to be honoured, and numerous extensions of time were given to the company to complete the task.

Petitioners argued that a financial penalty should be imposed on the company until the agreed service to Mordialloc was operational. In 1890 Cr McSwain was totally opposed to any extension of time but Cr Lamb Smith contended it was a shame to impose penalties because the company was composed of gentlemen who were “doing their upmost to put the tramway on a fair footing.”[22] Cr David Abbott supported the extension of time, as in his view, the present shareholders were not to blame. “It was the gentlemen who first took it in hand, and he could now see that their object was to cause a great flourish to get their land sold.” He was alluding to the roles of Charles Henry James and Harold Sparks amongst early investors in the company. [23]

In 1895 a seven year extension of time to July 1901was granted. [24] By February 2, 1903, after several warnings, the patience of the Council was exhausted. The Secretary of the Council was directed to write to the Tramway Company telling the directors that no further extension of time would be granted. The Directors were no doubt very relieved!

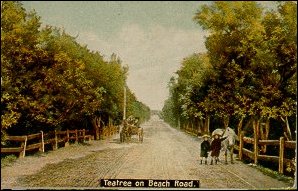

This was not the last communication from the Council to the company. As the tram line was in poor repair and constituted a danger to other road users, the company was asked to attend to it immediately. [25] The Secretary of the Council was again writing to the company in November 1908 on the need for repairs and on this occasion also sent a copy of the letter to the mortgagee. [26] By 1913 it was claimed that the tramlines were sometimes four or five inches above the road and constituted a danger to other road users given the width of Beach Road. [27]

Beach Road with tram lines to right of the photograph.

In addition to the condition of the track a problem was looming that had the potential for seriously affecting the income and future viability of the company. Local residents of Black Rock and Beaumaris wanted an improved service provided either by an extension of the railway system or the construction of an electric tramway. The horse drawn trams were operating at too infrequent intervals, commencing too late in the day, were slow and the fares was higher than would be charged on the railway. [28] A public meeting held in the Black Rock Coffee Palace earlier in the year supported the railway option and those present were urged to make their views known to a Standing Committee of the Victorian Parliament about to visit the district.

A previous inquiry in 1910 had recommended the extension of the railway line from Sandringham to Black Rock on the condition that the local municipal council provide the necessary land. The cost for the one and a half miles of track was estimated at £24,080 and rolling stock £6720. Cr D White, the President of the Shire of Moorabbin argued that the difficulty of finding the money for the land made the cause a hopeless one.

In December 1913 the Railways Standing Committee presented its new findings to Parliament. Rather than recommending a railway extension it proposed an electric tramway. A petition signed by many residents indicated if a railway was not possible then they would settle for an electric tramway constructed from Sandringham along Bay Road to Bluff Road and then south terminating at the corner of Bluff, Balcombe and Beach roads. [29]

One barrier to the establishment of a new electric tramway company was the existing lease arrangements between the Moorabbin Shire Council and the Beaumaris Tramway Company. The rights expressed in the lease did not expire until 1918. When it was suggested by the Minister of Railways that the lease should be revoked the company manager wrote a strongly worded letter defending the company’s position. He claimed the Council was trying “to oust the company from its rights without purchasing them as provided by the deed of delegation. … it seems inconceivable that the Ministry proposes to wipe out the company’s right, annex its property, and leave the company without compensation, when it has for so many years served the shore route, enabled settlement to take place and steadily advanced the council’s rates.” [30]

A Moorabbin News reporter claimed the situation was absurd. “The facts are that the council has been too lenient, the company claims the right to run a vehicle from Cheltenham to Sandringham, at any hour it likes, either on or off the tracks, they are not very particular and they have the impudence to claim that it has served the shore route and enabled settlement to take place.” [31]

In April 1914, Mr W Dickson, Secretary for Mines was appointed by the Minister of Public Works to conduct an inquiry to establish whether the Tramway Company had taken every precaution to secure the safety of passengers and to ensure the safety of passengers upon the streets on the route of the tramway. Various witnesses were called by the solicitors representing the Council and the Company to support their arguments. The president of the Automobile Club of Victoria said the tramway had been a menace to the safety of the travelling public for two years. He was supported by the Chief Engineer of Public Works. Mr F A McCarty, a civil engineer, reported that “for a stretch of 48 yards the ballasting was fine sandy loam between the rails, which would not bind solidly. The projecting tram rails were liable to burst the tyres of motor cars and upset other vehicles.” Alexander Lang, grazier of Rickett’s Point said the trams often went off the lines. On one occasion he was the sole passenger on a tram that “went off, instead of going on to the road it butted into the scrub”. Cyril Edwards, foreman of the Company the previous year said, “The cars frequently left the track, but the occurrences were not reported because they happened so often.” William Martin, a market gardener at Cheltenham said “a passenger suffering from a weak heart would get a terrible shock. Riding in a car sometimes was like riding on an ocean wave.” [32]

An expert witness, called by the Company’s lawyer, explained that “although some of the rails were loose, and through expansion some were buckled, there was no danger on the line with such slow moving trams. The undercarriages of the cars needed overhaul, but they were not dangerous at the rate of speed.” He did not think there was any likelihood of the trams falling to pieces. James Irvine, a driver on the tramway for about five years said the derailments had been due to sand and stones washing on to the tram track. An earlier witness had suggested the company was in a practically insolvent condition. This observation was supported by the Manager and Secretary, Henry Milner who said the company had “never paid a bean as a dividend”. He claimed the company always ran at a loss in winter and owed him over £800 for wages on a salary of £5 per week. [33]

After considering the evidence and the views of participants presented to the inquiry, Mr Dickson concluded that the tram line afforded, “a ready and favoured mode of access to the eastern foreshores of the bay, should be brought up to date, and not abandoned.” [34] This stimulated the company secretary and company solicitor to seek new investors to refinance the company, to allow it to relay the track and replace the horse drawn trams with petrol or electricity powered vehicles. A proposal to this effect was presented to Council but was never implemented. [35] Although the Beaumaris Tramway Company’s lease of the tramway track, granted by the Shire of Moorabbin, did not expire until February 1918, the company’s successive operational losses saw the withdrawal of the horse drawn tram service in 1915.

Footnotes

- Brighton Southern Cross, October 4, 1884.

- Defunct Company Records, Public Records Office.

- Brighton Southern Cross September 26, 1885.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, September 21, 1885.

- By December 1891 the Directors were C H James, W L Jack, G T Langridge, H Byron Moore, Thompson Moore, Geo Sutton, Robert Walker, Secretary & Manager Robert F Gow.

- Brighton Southern Cross October 27, 1888.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, October 5, 1885.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, December 13, 1886.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, January 17, 1887.

- Brighton Southern Cross, December 3,1887.

- Brighton Southern Cross, March 8, 1888.

- Chairman’s Half Yearly Report to Shareholders 1887,. Public Record Office - Defunct Company File RS 00932/P/0000 Unit 63 File 1075.

- Chairman’s Half Yearly Report to Shareholders, 1889.

- Sheehy, T., Sandringham Sketchbook History p42.

- Taylor, Fairlie, Memories of Early Cheltenham [Manuscript] 1958 - Royal Historical Society Box 41/2.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, July 7, 1890 p468.

- Manuscript Collection, La Trobe Library, Beaumaris Tramway Company Limited, Box 166/10©.

- Chairman’s Report to Shareholders, August 1889 Public Record Office - Defunct Company File, RS 00932/P/0000 Unit 63 File 1075.

- Chairman’s Half Yearly Report to Shareholders, February 18, 1890. Public Record Office - Defunct Company File.

- Chairman’s Report to Shareholders, 1909, Public Record Office - Defunct Company File.

- Brighton Southern Cross, November 19, 1887.

- Brighton Southern Cross July 12, 1890.

- Brighton Southern Cross July 12, 1890.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, June 17, 1895.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, March 7, 1904.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, 1908, p353.

- Moorabbin News, February 1, 1913.

- Moorabbin News, December 13, 1913.

- Moorabbin News, December 13, 1913.

- Moorabbin News, March 7, 1914.

- Moorabbin News, March 7, 1914.

- Moorabbin News, April 11, 1914.

- Moorabbin News, April 18, 1914.

- Moorabbin News, September 25, 1915.

- Shire of Moorabbin, Minute Book, July 24, 1915.